The nickname “Mr. Clean” has lingered since the height of Steve Garvey’s fame as a sweet-swinging first baseman for the Dodgers and Padres, as much a reflection of his success on the field as the wholesome, All-American image that followed him off of it.

Charming. Handsome. Unfailingly polite. Eager to sign autographs. Devoted to helping charities. A media darling. A successful businessman. All with a made-for-television grin.

Garvey is “a devoted family man,” read a biography once posted on his website. “As a father of seven children, Garvey understands that in the ever-changing world we live in there is a great necessity of being a man of honor, integrity and quality.”

Now, as the Republican front-runner in the race for a California U.S. Senate seat, Garvey has avoided detailed policy positions, instead relying on his name recognition and clean-cut image. His campaign website describes him as a “true role model,” he praised the party’s value of “personal responsibility” in a recent interview, and he called in an op-ed to “restore moral integrity in Congress.”

But the reality of Garvey’s life is more complex. The 75-year-old has struggled with debt, been repeatedly sued, faced a bitter divorce, and got two women pregnant before quickly marrying a third woman, his current wife, in a scandal that briefly made him a national punchline in 1989. He pledged in interviews at the time to take “moral and financial responsibility” for the children.

The Times editorial board interviewed some of the leading candidates for the U.S. Senate seat formerly held by the late Sen. Dianne Feinstein. The conversations covered the economy, housing and how they would navigate Congressional dysfunction.

Speaking publicly for the first time, the two children involved in the paternity imbroglio, now adults, told The Times that their mothers repeatedly tried to arrange meetings and phone calls for the children with Garvey, but he declined to communicate.

Also speaking publicly for the first time, Garvey’s oldest child from his first marriage said he cut off almost all contact without explanation about 15 years ago in a move that she still finds painful.

Krisha Garvey, 49, said she is not active in politics but agreed to speak to The Times about what she characterized as “complete abandonment” of herself and her three children by her father because she felt it was important for voters to understand that her father’s public image hasn’t always reflected his personal life.

“There’s something lacking in him, something not authentic,” she said. “To be a man of the people, to truly have experience of being a totally complete, loving family man … I wouldn’t want the people of California to buy into that just because he hit a ball really well.”

Subscribers get early access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers first access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Now both 34, the two children Steve Garvey had with the two different women in 1989 said in a joint statement that they have no partisan or ideological position on the Senate race. They have moved forward with their lives without the father they’ve never known.

“In our childhoods, multiple efforts were made through attorneys to arrange a meeting or even a phone call with Mr. Garvey, but he declined every opportunity,” Slade Mendenhall and Ashleigh Young wrote. “Thus, we have never known him, and our only relationships with him were through the family court system.”

Young told The Times the only time she has spoken with Garvey was a chance encounter in line at a Park City, Utah, ski lodge shop when she was in middle school that was “very brief and a bit awkward.” Mendenhall said he has never met or spoken with Garvey.

Garvey’s campaign did not respond to detailed questions from The Times about his children, his financial dealings and whether his public image has matched his private conduct, but instead released a statement.

“The challenges I faced after retiring from Major League Baseball four decades ago were pivotal in shaping the person I am today,” the statement said. “The lessons learned about personal accountability and integrity have made a profound, lasting impact on my life. I’m the luckiest man to be happily married to the love of my life, Candace, for the last 35 years, which I believe demonstrates my growth and commitment to family values. These experiences have equipped me to better understand the adversities others face in their lives, and to serve the public with empathy and integrity, something that has been lacking in Washington, D.C.”

After a quiet start in his first run for public office, Garvey, a Palm Desert resident, has hit the campaign trail. Stops in recent weeks included California’s border with Mexico, the Salton Sea, an almond company in Kern County, a Compton bakery, a tour of Skid Row in downtown Los Angeles, a homeless encampment in Sacramento, and meeting with Jewish community leaders in Pleasanton.

Garvey, who describes himself as a “conservative moderate,” has said he voted for President Trump in the past two elections but he hasn’t articulated detailed positions on the issues.

During the Senate debate on Jan. 22, Garvey refused to say whether he’d vote for Trump a third time. Asked by a moderator about his policies, Garvey said he’s “taken strong positions” and offered examples, like his advocating for a “strong audit” of spending to combat homelessness, his call to close the border, and the need to “get crime off the streets” and “fund the police.” Campaign videos have struck a similar chord, promoting the need to “take a stand against out-of-control inflation” and “achieve peace through strength.”

The latest poll from the UC Berkeley Institute of Governmental Studies — co-sponsored by The Times — shows Rep. Adam Schiff (D-Burbank) supported by 21% of likely voters, followed by Rep. Katie Porter (D-Irvine) at 17%, and Garvey with 13%. Rep. Barbara Lee (D-Oakland) rounded out the top four with 9%. The top two finishers in the March primary face off in the general election in November for the seat once held by the late Dianne Feinstein.

Jack Pitney, a professor of politics at Claremont McKenna College, said Garvey has a serious chance to advance to November, but doubted whether he had a real shot to win unless a major scandal hit the Democratic candidate. Garvey’s troubled relationships with some of his children, he said, could become a liability if he started rising in the polls.

A Republican will always be a long shot to beat Reps. Adam Schiff or Katie Porter in the U.S. Senate race. Steve Garvey is hoping that baseball can make it happen.

Garvey’s strength, the professor said, boils down to his name recognition with members of a “certain generation” who remember Garvey’s exploits with the Dodgers and Padres in the 1970s and 1980s.

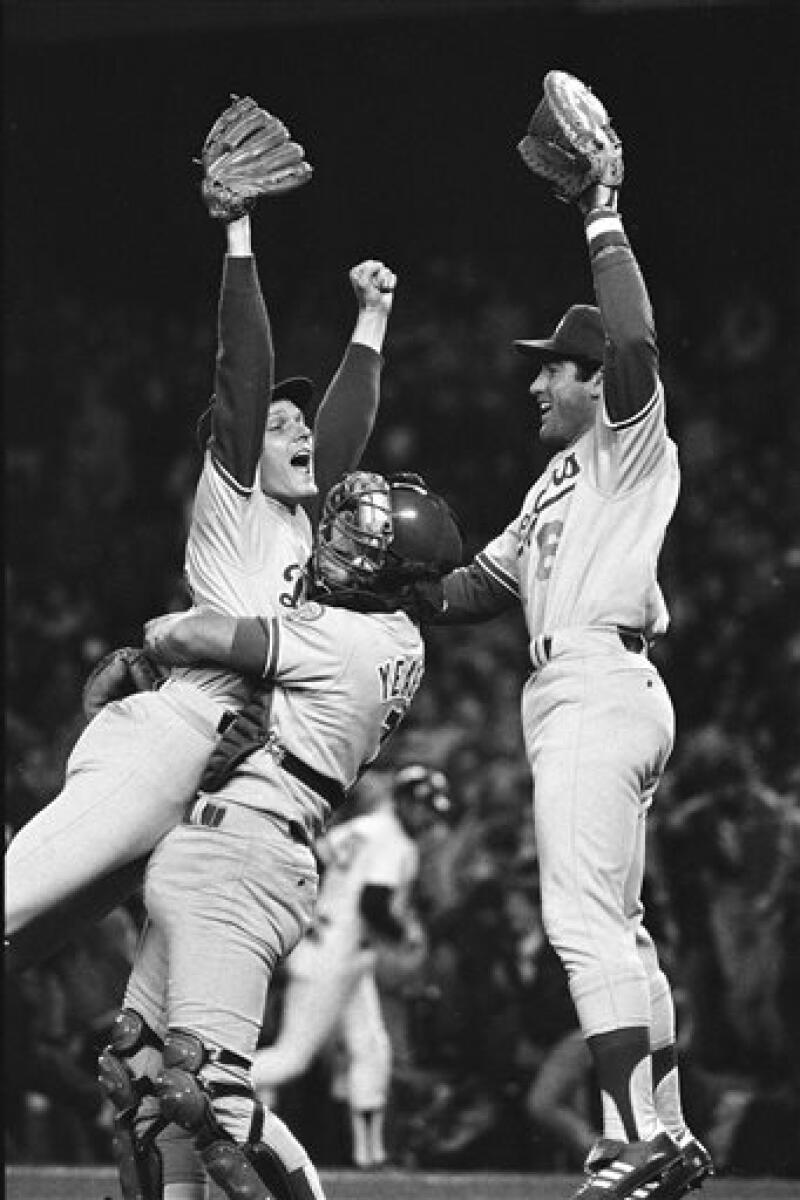

The one-time Dodgers batboy was selected for 10 All-Star games, won a Most Valuable Player award, set a National League record by playing in 1,207 consecutive games, earned four Gold Gloves for his defense and helped the Dodgers win the World Series in 1981. He was as dependable as bumper-to-bumper traffic on the 110 Freeway that runs near Dodger Stadium, collecting 200 or more hits in a season six times and ranking among the games-played leaders in 10 seasons. The faithful who packed stadiums to watch him play loved the clean-cut, aw-shucks, God-fearing superstar.

“He collects art, not phone numbers,” legendary Times columnist Jim Murray wrote in 1974. “He’s on the team bus more than the driver. His idea of a good movie is one where everyone keeps his clothes on and the good guys win. He visits crippled children’s hospitals, not discotheques. … Garvey is hopelessly addicted to malted milk and getting to bed early.”

He was as smooth in front of television cameras and microphones as he was scooping up ground balls to first base. He appeared on game shows, sitcoms, talk shows, even the cover of Sport magazine eating apple pie festooned with American flags. Companies flocked to use him as a pitchman for products like Vitalis Hair Tonic and Swanson Hungry-Man frozen dinners. A junior high school in Tulare County was named after him. Garvey and his then-wife Cynthia — he filed for divorce in 1983 — were called Ken and Barbie in newspaper stories that cast them as a Southern California ideal.

“He was the face of the franchise save for [Dodgers manager] Tommy Lasorda, as much as any player had been maybe since they came over from Brooklyn,” said Jason Turbow, whose book “They Bled Blue” chronicles the team’s path to the championship in 1981. “In many ways, he was the Dodgers.”

1

2

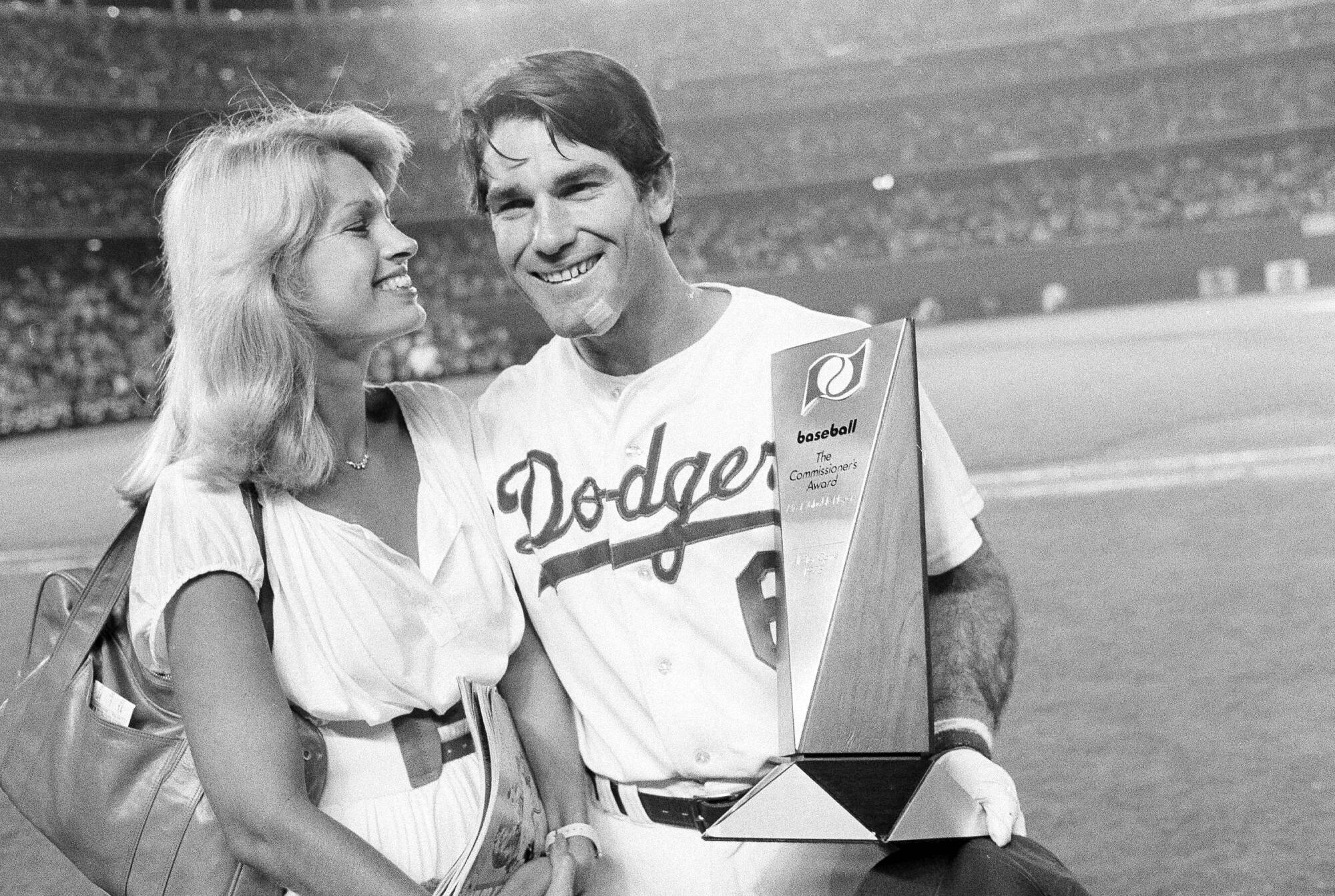

1. Steve Garvey, left, watches Dodgers manager Tommy Lasorda try to deal with nine Hula-Hoops during spring training in 1982. (Los Angeles Times) 2. Steve Garvey, right, celebrates with teammates after the Dodgers beat the New York Yankees to win the World Series in 1981. (Associated Press)

The adulation reached such heights that in an interview with Playboy magazine in 1981, Garvey said he had been “approached by very high-profile” Republicans and Democrats about running for office and “either I start at the U.S. Senate or nothing.” He hoped to “develop ideas and principles that will set examples for people.” If a political career materialized, Garvey told the interviewer, he would consider trying for president because “I know if I were elected to that position, it would be nothing short of my complete, total dedication.”

But the attention sometimes grated on other players.

“Some of his teammates thought the Garvey persona was too neat, his near-immaculate lifestyle too perfect, and that what they were witnessing in his daily embraces with the media, in his publicized visits to semi-invalids in hospitals and in his marathon autograph and photo sessions was nothing more than image making,” Sports Illustrated’s William Nack wrote in 1982. “What they believed they saw was a cynically calculated polishing of the … image for personal gain — a businessman, blasphemy of blasphemies, in [legendary Dodgers player] Gil Hodges’ uniform.”

In an autobiography released in 1986, Garvey insisted the virtuous image was the real thing: “All that autograph-signing and hand-shaking and cheek-kissing, that’s how I am and have always been. … Some guys can’t be bothered, but when I look into those little faces, I can’t say no. I remember when I was a kid and ballplayers had time for me — it made me happy.” He talked about the need for positive role models and that there should be “at least one straight arrow among the swingers.”

Garvey, a former All-Star first baseman for the Dodgers, may upend the race to fill the U.S. Senate seat held by the late Dianne Feinstein since 1992.

But in early 1989, less than two years after his final game with the Padres, Garvey was accused of getting two women pregnant — including one he was engaged to — before marrying a third woman, his current wife, after a brief courtship. He tried to explain what happened in a series of interviews. Both women, he said, led him to believe they were using birth control.

Bumper stickers proclaimed: “Steve Garvey is not my Padre.”

During a “Golden Girls” episode that spring, the character Sophia Petrillo quipped: “I just hope I’m not carrying Steve Garvey’s baby.”

The Times described the situation in a headline as an “accidental double play” and assured readers that Garvey’s long-discussed political prospects remained intact. He promised in the same story to “accept the moral and financial responsibility” for the children because “there is a right way and wrong way to deal with moral situations, and I believe this is the right thing to do.”

DNA tests showed Garvey fathered the children. The scandal landed in court. He was ordered to pay child support. Garvey was also embroiled in a divorce and child visitation dispute with his first wife, Cynthia, that played out in headlines and grew so contentious that a Times story referred to it as “The War.”

The Federal Trade Commission accused him in a 2000 lawsuit of making deceptive claims in infomercials for a weight-loss product; a federal judge ruled he didn’t engage in false advertising. In 2006, a Times investigation found that Garvey and his wife, Candace, had “neglected bills large and small, leaving dozens of people who either worked for them or sold them merchandise wondering if they were ever going to get paid” and that Garvey “unilaterally decided to cut in half” the child support for his son born in 1989.

In recent years, he has appeared at autograph shows and Dodgers fantasy camps, given speeches and promoted dinner rolls, CBD pain-relief products and reverse mortgages. His charitable work has included raising awareness about prostate cancer and promoting baseball in Ireland.

“Steve will pick up the phone and do whatever we ask of him and is incredibly gracious about it,” said John Fitzgerald, founder of the nonprofit Irish American Baseball Society, which celebrates the contributions of Irish Americans to baseball. The society named Garvey an ambassador last year.

GOP Senate candidate Steve Garvey may not have much chance against a Democrat, but he could make the race interesting and give Republicans someone to rally around.

Among his other endeavors, Garvey offers to film personalized videos for fans on Cameo for $149.

“Once I started doing this, it’s been amazing, the amount of well wishes and satisfaction that I’ve had in doing something special for the fans,” Garvey said in a promotional video. “We’ve just had a great Mother’s Day run and the videos that came back of crying and laughing, it was so heartwarming.”

Amid pitches for Cameos and other products, Garvey’s Instagram feed portrays a family man. Garvey posing for a family photo on Christmas. His youngest daughter preparing to attend the Stagecoach Festival. On the Dodger Stadium field with her: “Special #Dad #Daughter night at the #2022 All-Star Game.” At the Kentucky Derby the same year with his wife. The caption read: “One more memorable event to our life experiences.”

(Garvey had two children with his first wife, two children with two different women in 1989, and three children with his current wife, in addition to two children she brought into their marriage.)

Garvey’s oldest daughter, Krisha, fondly recalls childhood memories of her father, including him still wearing his Dodgers uniform when he would jump in the pool at the family home in Calabasas with her and her younger sister, Whitney. (Whitney Garvey could not be reached for comment.) Krisha said she is athletic and competitive like her dad, an avid tennis player who remembers his coaching when she was young. His words echo in her mind every time she steps on the court: “Happy feet, happy feet.”

Steve Garvey dedicated his autobiography published in 1986 to Krisha and Whitney and, as part of the dedication for another book in 2008, mentioned “my children” and Krisha’s oldest son.

About 15 years ago, she said, her father stopped calling and taking her calls. It shocked her. She didn’t understand what had happened. One day, she said, she caught him on the phone. He told her “this is how it’s got to be, Krish” but otherwise did not explain the estrangement, she said. The little communication between them largely consisted of brief texts, emails, and phone calls she initiated, according to Krisha.

The hurt and confusion, she said, has left her crying “like a little girl” on almost every one of her birthdays in the past decade and a half.

Just because you were a Dodger great and a stellar ball player doesn’t mean you should be in the U.S. Senate, Mr. Garvey

She said it was “shameful” that her father hasn’t tried to have a relationship with her three sons — his grandsons. In an email sent to him in March 2011 and shared with The Times, she attached a photo of one of her sons playing tee-ball and wrote, “Dad, I still don’t know how you sleep at night. You’ve lost so much you won’t ever get back.”

His absence, she said, has motivated her to turn her “boys into men who are accountable.”

“He has not been accountable, not to his family,” she said.

Among the handful of interactions with her father since the severing of the relationship was a call from him in September to let her know about his Senate campaign. Krisha recalled that he asked how her life was going and said he would probably run, but would keep his family out of it. Those isolated conversations have felt “cold,” she said, like a “sensitivity chip” was missing and he was going through the motions with little or no feeling.

Krisha, an esthetician and artist who co-owns an apparel shop in West L.A., said she believes that a politician “needs to have dignity, to be grounded” and she wonders about his character.

“I think my dad is very simplistic. He can tell you a good stupid dad joke and keep it very superficial and very light,” she said. “He can talk around a thing really well, and he can sell a thing. What’s underneath all that though? It’s questionable.”

Told of the personalized video messages her father sells for $149, Krisha teared up.

“He doesn’t acknowledge his [eldest] daughter, her birth, that’s upside down wrong,” she said.

Mendenhall and Young, the two adult children who said they have never known Garvey, emphasized in their statement to The Times that their other relatives taught them the value of family and they “never wanted for love.” Their mothers introduced the half-siblings when they were 3 years old and they remain close. Mendenhall is a lawyer in Georgia; Young is a stay-at-home mother in Japan.

“Now,” they said in the statement, “as adults looking back as well as forward to the next generation of our family, sons and daughters, nieces and nephews, we are ever more committed to being present for the ones we love, for every ballgame, every dance recital, every birthday, and every Christmas. We know that so much of life begins with simply showing up, and we would not miss a second of it — not for the world.”

In an interview with The Times, Young said she hopes to have a relationship with Garvey one day. She wants to introduce him to his 2-year-old grandson. Her husband, a Navy officer, has been a hands-on father.

“At the end of the day I don’t really understand how a man wouldn’t want a relationship with his kids,” Young said. “I have a beautiful son. It’s sad he won’t know his grandfather.”