Lawrence Tolliver wasn’t ready to say goodbye, but circumstances were beyond his control, and the timing was downright cruel.

The South Los Angeles building that housed Tolliver’s Barber Shop was being sold, and the new owner had different plans for the space. Early in December, the same month a documentary on his legendary shop was set to premiere, Tolliver found out he’d have to move out by Christmas.

“On to the next,” he said one day, trying to stay positive. He told me he had read a column of mine in which the late Norman Lear said life is a series of transitions from what’s over to what’s next.

But Tolliver, approaching 80, wasn’t sure what was next, and he was hurting. At one point, as he packed away his belongings, he was too worked up to even talk about it.

“It’s hard enough going through it,” he said.

Tolliver has been a barber for more than half a century at three locations, the last 12 years on the south side of Florence Avenue near Western, where the walls were plastered with images of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., Nelson Mandela, Muhammad Ali and the Obamas, among other Tolliver heroes.

California is about to be hit by an aging population wave, and Steve Lopez is riding it. His column focuses on the blessings and burdens of advancing age — and how some folks are challenging the stigma associated with older adults.

He was always great with the shears, whatever the generational style shifts, and his regulars included women. Children followed their fathers and grandfathers into the shop and into adulthood.

But that was only half the story.

By the force of his personality and the breadth of his humanity, Tolliver built a gathering place for people who dropped by, through the decades, whether they needed a haircut or not. They came to speak up, to listen, to laugh and to learn.

Lawrence Tolliver has been master of ceremonies, chief psychologist, traffic cop and symphony conductor in a hallowed hall where people talked about history and honor, glory and grievance, Watts, Rodney King, epidemics of drugs and crime, the rise of Obama and the relentless scourge of racism.

His shop has been a place where kids were in the company of role models including doctors, lawyers, cops, ministers, teachers, principals, engineers, merchants and laborers. And Tolliver threw his support to community causes, promoting public and mental health initiatives, backing youth sports and giving free haircuts to homeless people.

“This is a safe space,” Karen Bass said during an October 2022 visit as a candidate for mayor of Los Angeles, joining a long line of politicians and public officials who have dropped by the shop to listen and to be heard. “It’s where people come to exchange views and they can do it in the comfort of their community. And people learn while they’re having these discussions.”

I got a haircut just before Christmas, when the walls were already half-naked. Tolliver handed me a Miles Davis poster as a memento, knowing I’m a jazz guy, and it broke my heart to see the dismantling of the shop where I’d been welcomed, educated and entertained — the shop where I’d met Lawrence’s wife, Bernadette, and much of the family.

My first visit was in 2001, when the shop was across the street on the north side of Florence. I was curious after watching a mayoral debate where a young man in the audience told me he liked Antonio Villaraigosa, but the elders at his barbershop told him he owed Jim Hahn a vote because County Supervisor Kenneth Hahn, Jim’s dad, was seen as a man who cared about and delivered for the Black community.

What I got that day was a spirited debate about the election, and I kept going back for more. Tolliver and the gang weren’t always out to work up a sweat solving the riddles and injustices of the world. Sometimes the shop was a place to take a break from it all, or watch Tolliver bust everyone up with his dance moves. Sometimes it was a place for idle chatter about the rhythms of life, sports, music, love.

But they got down to business, for sure, in theatrical barbershop style, with trenchant, high-volume takes on the issues of the day, frequently from the left but certainly not always.

I saw Tolliver rail against police brutality but stand up for law enforcement. One of his three sons became an LAPD officer and a succession of police chiefs visited the shop. They included current chief Michel Moore, who apologized in 2020 to a room full of Tolliver’s regulars for having equated the criminal acts of protesters in Los Angeles with the actions of the Minneapolis police who murdered George Floyd.

Several years ago, Sandra Evers-Manly —a Tolliver family friend, president of the Black Hollywood Education and Resource Center, and a cousin of slain civil rights activist Megar Evers—began working on a documentary about L.T.’s.

Evers-Manly and I both went to Pittsburg High School in the Bay Area, though I’m much older and didn’t know her until she took on the Tolliver project. It wasn’t an easy film to make, because the pandemic hampered development, and Evers-Manly is bicoastal, splitting time between California and the D.C. area, where she retired after a long career as a Northrop Grumman executive.

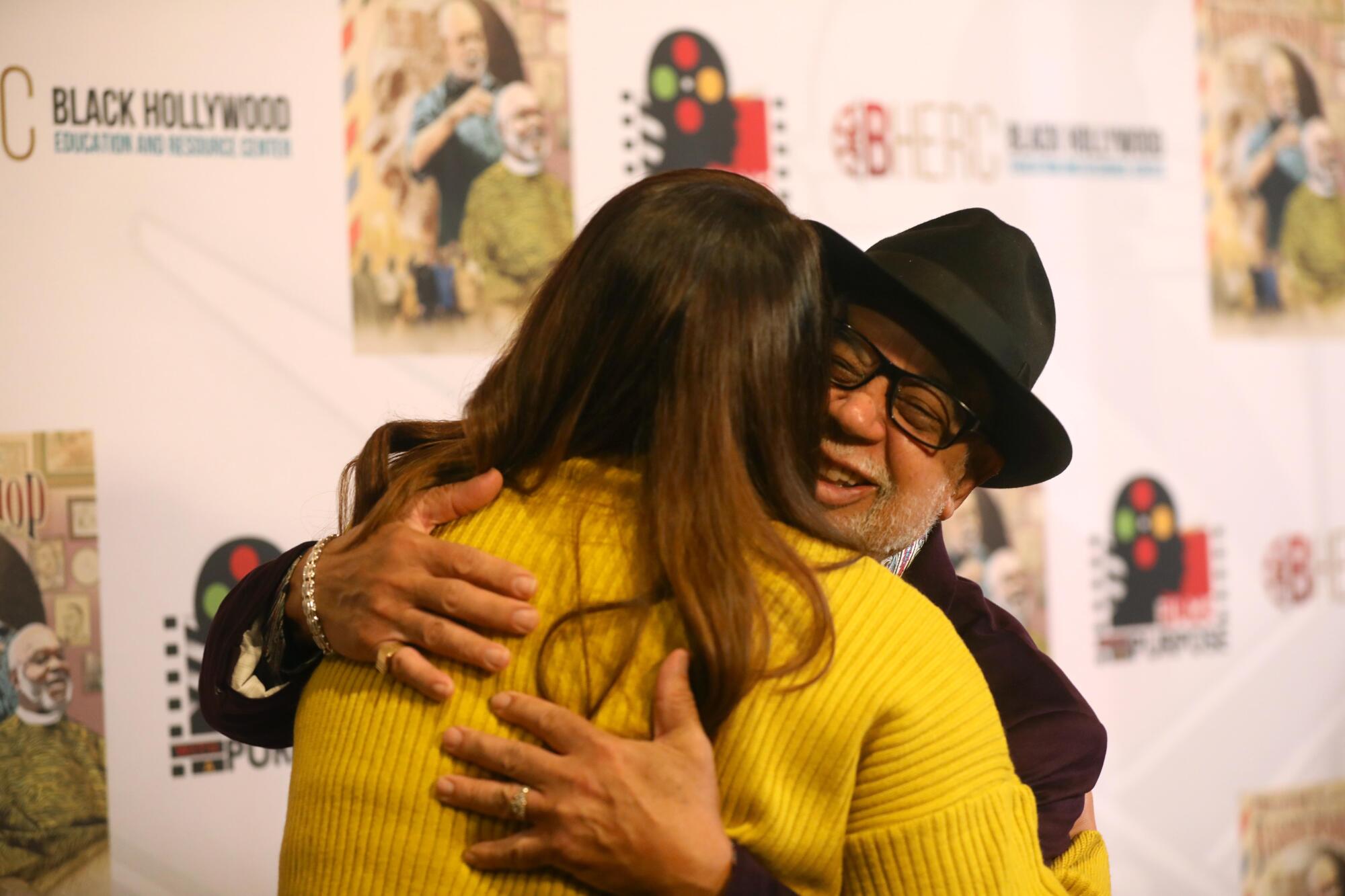

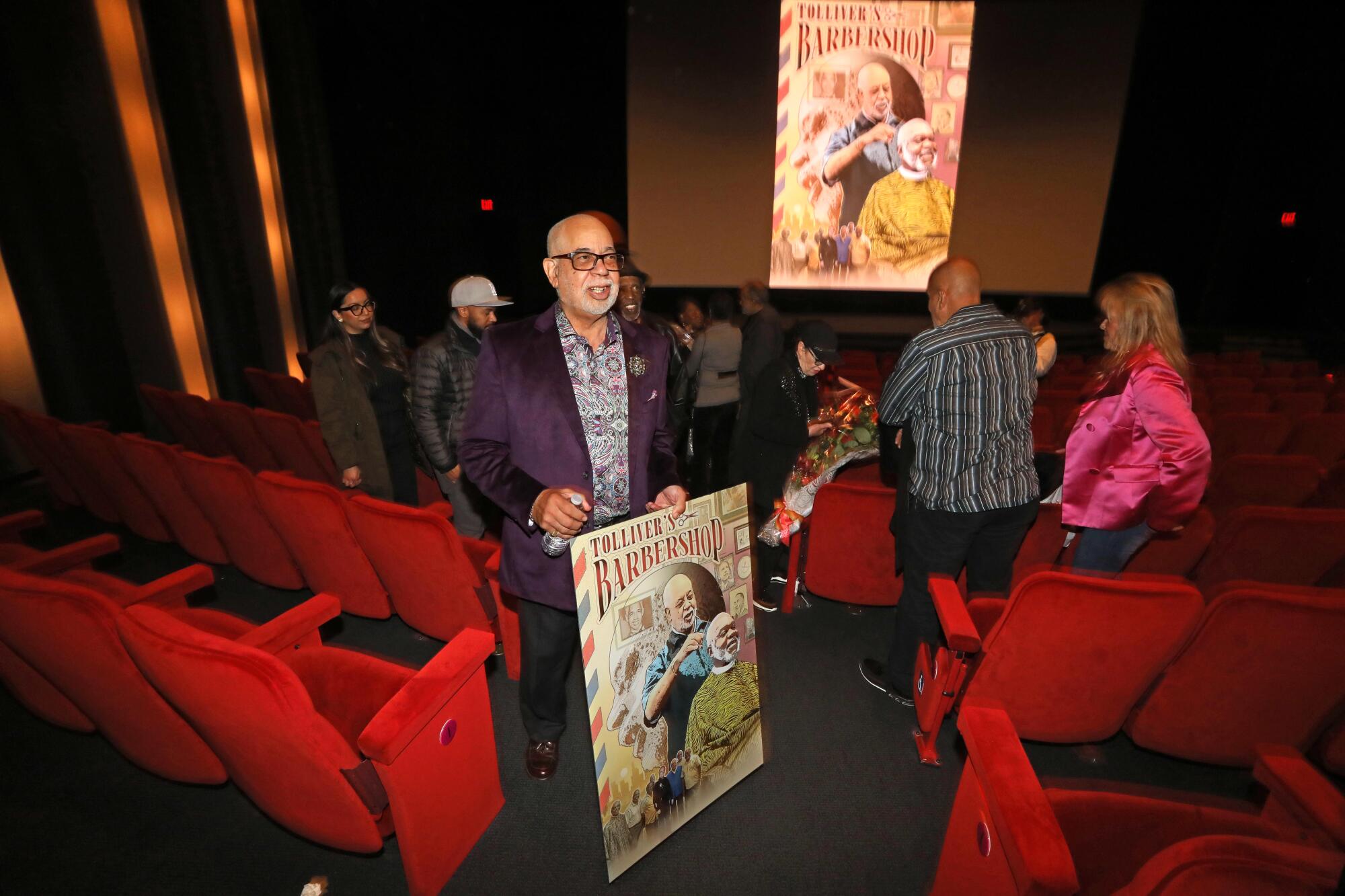

But she’d seen firsthand the magic of L.T.’s barbershop, and Evers-Manly wanted to capture it for the world to see. So she kept at it, and on Dec. 29, at the Director’s Guild of America Theater on Sunset Boulevard, more than 400 people — many of them Tolliver’s customers — attended the red-carpet premiere of “Tolliver’s Barbershop,” which beautifully captures the spirit of an establishment that will be sorely missed.

By then, Tolliver had made peace with the unfortunate juxtaposition of a movie touting an institution that had just shut its doors. He told the audience that some of the characters in the film had died, but the documentary would keep their memories alive. Evers-Manly is arranging an East Coast showing and hoping to get into festivals and distribution channels.

In rationalizing the closing of his shop, Tolliver reminded me he’d scaled back to working part time and was only cutting the hair of a core group of customers and friends. So now there would be a bit more trimming, he said, and he was still considering the when, where and how of that before the holidays.

“He’s a man of his community,” the Rev. James McKnight of the Congregational Church of Christian Fellowship in Harvard Heights says in the film. “If he had an opportunity to go to the suburbs or to the Valley or wherever, and there was a great financial opportunity, I think he would say, ‘Hey, no, man, this is where I am, and this is where I’m going to be until I die ….’”

Though he was born in Alabama, Tolliver says his roots are in L.A., and he still believes in the community he calls home.

“The majority of people in this neighborhood are hard-working, God-fearing, law-abiding residents,” he says, and he adds that he wants to be remembered as somebody who “tried to love someone. I tried to do my best to encourage people.”

A few days after the premiere, I asked Tolliver how he was doing.

He texted me a favorite little ditty of his.

“I am not dead. My shoulders hold a good head. Life has not completely fled. So I will cut hair. Somewhere, somehow.”

steve.lopez@latimes.com