- Share via

The Noname Book Club Headquarters isn’t a typical meetup inside your average library.

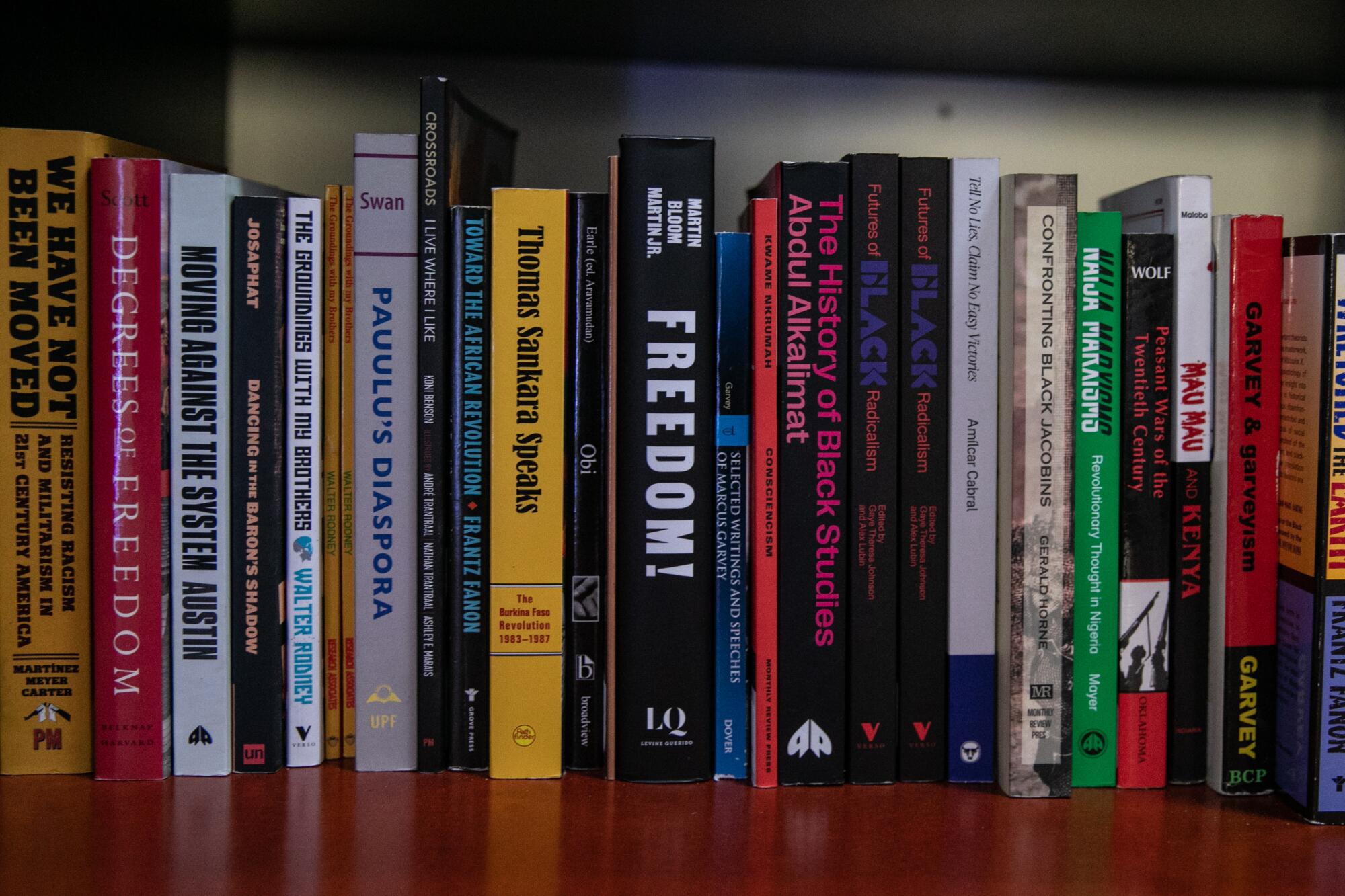

Inside the Book Club Headquarters on Jefferson Boulevard, which houses monthly events founded by Chicago rapper Noname, books are sorted by genre labels such as “constructions of race” and “chocolate cities.” The Wi-Fi password, posted on a corkboard in the lobby next to Christmas photos from the club’s “incarcerated homies,” is “BlackLiberation.” And, a couple of Saturdays a month, the library hosts a popular open-mic night.

A few weekends ago, Natalie Matos and other staff members spent the early evening rearranging book stands and couches to make room for the Noname Book Club event. They added a speaker, two dozen folding chairs and floor spotlights. Around 6:30 p.m., local singers, poets and musicians began adding their names to a sign-up sheet. Nearby, Matos exchanged hugs with familiar faces.

The night’s MC is Jean Deaux, a well-known Chicago musician and friend of the library. She welcomed the crowd that had grown to about 50 and set ground rules for the program: “There will be no homophobia, no transphobia, no anti-blackness, no fascist s—, and no MAGA s—. We clap for everyone from the moment I call their name until they reach the stage.”

After years of online organizing, the Radical Hood Library opened in 2021. Formerly a vacant furniture store, the little newly-painted blue building on the corner of Jefferson and 3rd anchors the Noname Book Club, a BIPOC reading group founded by Chicago rapper Fatimah Warner, aka Noname. Each month, the headquarters coordinates 20 chapter meetups from Oakland to D.C. Over the years, the space has become home to new programming, including film screenings and “Kid’s Black Power Reading Hour.” Almost a year ago, they introduced open-mic night to “create more spaces of Black joy.”

“After the isolation that was felt during the pandemic, our work of holding space for people to feel seen and heard was received well,” Natalie Matos said. “We found that people were really looking to be in community.”

Anastasia Antoinette, 34, was among the first performers of the night. Antoinette, originally from Houston, has lived in Hollywood for three years. Though a first-timer at the event, she was smiley and confident. Accompanied by her friend and guitarist Funsho, Antoinette riffed on the chorus of an R&B song they wrote called “More.” Antoinette’s hands rested in the pockets of her black athletic shorts as she nodded to Funsho’s strumming.

Next up was Micah Bournes, 35, who drove from Long Beach to perform “Native Tongue,” a spoken-word poem on cultural assimilation and Ebonics. Bournes started rapping as a full-time gig years ago, but he recently got into poetry after being affirmed in spaces such as this one.

“I didn’t even know I liked poetry because, when I learned about it in school, it was all dead white people,” Bournes said. “This is the kind of stuff I actually like.”

Oluwafunmilola “Lola” Sule, 23, used her three minutes to perform a scat exercise she calls “flowing.” Wearing a white shawl and dangling earrings emblazoned with the words “Unapologetically Black,” Sule invited the crowd to sing along.

“I’m manifesting a choir tonight, so lift your voice and sing with me.” Her improvised chorus is simple; a dozen times, she repeats “Mo ti de, mo ti de le,” which means “I’ve arrived. I’ve come home” in Yoruba.

“Doing open-mic nights like this is at the forefront of my goal to pursue music seriously this year,” Sule said in an interview afterward. “I’m learning to trust this new direction.”

At intermission, Matos and another staff member, Sage, helped interested guests check out books — a process that only requests a name and email. With this, loans operate on the trust system–with no late return fees. Deaux also offered the crowd merchandise and refreshments (water or White Claws), which were available in the lobby. The proceeds from these purchases and donations on Patreon fuel the library; it pays for overhead, staff and prison program books.

Toward the end of the program, Matos introduced the audience to Tyrone, an inmate in Los Angeles who has championed the HQ from behind bars. After he received books and information about the Noname Book Club, he called the library asking if staff could record his performance over the phone. Quoting Gil Scott-Heron, Tyrone’s raspy voice reminded the audience that “the revolution will not be televised.”

The club’s prison program has grown exponentially in two years, Matos said in an interview with The Times. The year HQ opened, they shipped less than 50 books; this month alone, they shipped 1312. Although they ship to 37 states and 300 facilities nationwide, most of the program’s members live incarcerated in the South.

“We’ve also grown more intentional with what building with folks inside prison looks like. We send out reading questions with our books,” Matos said. “We uplift our incarcerated members’ analysis on social media and in our meetings across the country as another way of bridging the walls prison builds between our community.”

At the end of the night, Noname, who slipped into the venue right before the first acts and watched humbly from the lobby, took to the stage to perform unreleased music. Deaux, also a Chicago native, got choked up when introducing her friend.

“We both came up making music in a space like this. I am grateful for your contributions and feel honored to be a part of it,” Deaux said, “Noname is the reason that this is all possible.”

Before she took the stage, Noname borrowed an iPhone dongle from another performer — an act she referred to as a “socialism doing.”

“It’s funny how I can perform in front of a ton of people, but here I get nervous,” she laughed. “Can I do some new s—?”