Are you ready for a blackout? How Californians can keep their lights on

Most Californians expect to endure multiple blackouts this summer. Yet more than 70% have no source of backup power for their homes.

Those findings come from a new online survey of 1,000 California adults by Haven Energy, which admittedly is not an unbiased observer. The company helps people install home backup battery systems.

Nevertheless, the survey points to a puzzling disconnect (no pun intended): Most respondents expected their power to go out one to three or more times in the next three months, yet they had no plan for keeping their air conditioners and refrigerators running, their phones charged and their homes connected to the internet.

You may not recoil at the idea of losing power for a few hours, but in this state, blackouts can last for a day or more. You can last a day without Netflix, but what about air conditioning?

The threat is particularly acute for Californians in high fire risk areas, where electric utilities have been preemptively shutting off power during windstorms. But even in cities, higher temperatures are straining the power grid, raising the specter of brownouts and blackouts if residents don’t manage their electricity use well.

California has seen more outages in the last five years — 99 — caused by “major disturbances and unexpected occurrences” than any other state except Texas, according to the Fixr website’s analysis of data collected by the federal government. On average, these blackouts lasted almost 10 hours; the longest lasted two and a half days.

Surging demand for electricity during a heat wave last September could have caused far more outages and even some rolling blackouts, utility executives warned. But the power companies averted the worst effects by persuading their customers to ease up on the juice in the late afternoon and evening, when demand strained the grid.

If you want to face the next outage armed with more than candles and flashlight batteries, you have options that vary in price, capacity and environmental impact. There are some longer-term steps to consider too. Here’s a rundown of the major alternatives, from most affordable to most expensive.

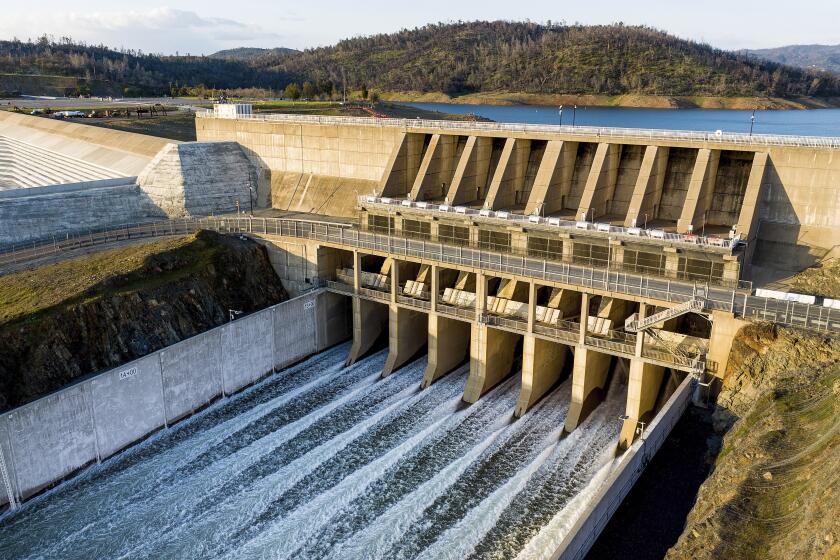

State officials say the winter’s wild weather helped refill hydropower generators, decreasing the risk of dangerous electricity outages this summer.

Portable batteries for limited power

If you have modest goals — for example, keeping your refrigerator running, or just recharging your phones — a portable “power station” could be a good solution, said Joe O’Brien-Applegate, an energy expert at the Natural Resources Defense Council. These devices “can hold a charge for a very long time, so that they’re ready when you need them,” he said. They can also be charged fairly quickly.

Prices range from about $600 to a few thousand dollars, depending on how much power you want to store. A power station with a 1-kilowatt-hour capacity — enough to power an energy efficient refrigerator for nearly a full day — costs about $1,000.

These devices can supply enough power “to keep the necessities going for as long as [a typical] outage would last,” O’Brien-Applegate said. Smaller, less expensive models are available too, but those may not do much beyond recharging your phones and other battery-powered devices.

No tax credits are available for portable power stations, but utilities offer rebates that can bring down the cost. Edison, for example, offers a rebate of up to $150 to customers in areas considered at high fire risk; each household can receive rebates for up to five power stations.

One other interesting feature is that some models come with small solar panels that can recharge the batteries while the grid is down — as long as the sun’s up.

Unlike wall-mounted batteries, portable power stations are a solution available to renters, said Laura Feinstein of the San Francisco Bay Area Planning and Urban Research Assn., a public policy think tank also known as SPUR. Another possibility on the horizon: A startup is developing electric bikes whose batteries can be used to run your appliances during a blackout, she said.

Here’s what to do before, during and after a power outage as a heat wave continues to scorch California.

Powering your whole house when the grid fails

Your first thought might be a diesel generator. You could also get one fueled by your home’s natural gas line or by propane. But if you’re looking to power your whole house, you’ll probably need a generator that will set you back $5,000 or more for equipment and installation.

In addition to the expense, there are the issues related to fuel and emissions. All fossil fuel-powered generators emit planet-warming carbon dioxide. O’Brien-Applegate said loosely regulated diesel generators are “some of the dirtiest engines that are allowed.” (The emissions from diesel engines have been linked to cancer and other ailments.) You may not use them often, “but it does have an impact, being right next to your house,” he said.

In addition, O’Brien-Applegate said, diesel fuel can go bad — fuel vendors and experts online say the life span is typically six to 12 months. And as with any fuel-burning engine, a generator needs to be outside or well-vented to the outside to avoid carbon monoxide poisoning.

PG&E and Southern California Edison power cuts: Here is how to survive a blackout

Batteries pose none of those issues, although they can go disastrously wrong if installed improperly or abused. According to the National Fire Protection Assn., a battery can catch fire or even explode if physically damaged, overheated or overcharged. That’s why the association has issued safety standards for installers to follow.

As with a generator, though, it takes a lot of battery to power a whole house for a day or two. And that makes the wall-mounted versions even costlier than the diesel versions. According to EnergySage, a Boston-based online marketplace for clean energy technology, a fully installed whole-home battery will cost $10,000 to $20,000.

(You may be tempted to install the batteries on the cheap with the help of a handyman, but be careful: California law requires anyone hired to do a job involving $500 or more in materials and labor to be a licensed contractor. The battery manufacturer may also limit the warranty to installations done by an expert. Besides, this isn’t like plugging a bunch of AAAs into a remote control; the battery’s output must be converted from direct to alternating current before it’s fed into your electrical panel.)

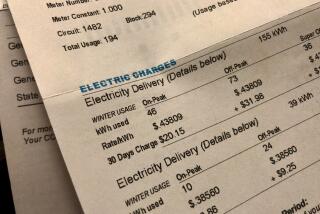

Once you factor in the 30% federal tax credit, the cost of a battery comes down considerably — assuming you pay enough in taxes to take full advantage of the credit. The state’s investor-owned utilities also offer rebates for home battery systems connected to the grid; Edison and Southern California Gas are currently offering 15 cents per watt-hour of storage capacity, which, for a 10-kilowatt-hour battery, translates to $1,500.

For low-income households and homeowners in areas with high fire risk or multiple blackouts, the incentive rises to 85 cents per watt-hour, enough to cover most of the cost of a battery. But the rebates decline as more people sign up for them.

Even without subsidies, a battery can save money on your electricity bill by taking over from the grid when your utility’s rates are at their peak. Those savings can help pay back what you spent on the battery. Haven Energy Chief Executive Vinnie Campo said that many of his customers should be able to recoup their costs in 10 to 12 years, although your experience may vary.

Last summer, a dangerous heat wave across California pushed the power grid almost to the brink. Officials say the state is better equipped to weather such extreme heat this year, but late summer could still be a test.

Granted, the savings would be greater if you installed solar panels on your roof along with your battery. But that would roughly double your upfront costs, according to EnergySage.

Big tax credits and subsidies are available for solar panels too. Beyond that, low-income homeowners in eligible communities can apply to the Disadvantaged Communities — Single-family Affordable Solar Homes program for financial incentives that could be large enough to cover the entire cost, if funds are still available.

GRID Alternatives, a nonprofit based in Oakland, has helped more than 14,500 California homeowners obtain solar panels through this program. Liza Nobel, GRID’s director of outreach marketing, said the nonprofit is “really interested in making an affordable or no-cost option available for battery storage for our communities,” in addition to providing solar and battery systems, and is “working with industry partners, state government and regulators to make that possible.”

Plugging in your EV

When it introduced the Lightning version of its F-150, Ford ran commercials featuring the vehicle doing something never seen in a truck commercial before: powering a house during a blackout. And the Lightning is one of several EVs with “bidirectional” power — able not just to draw it from the grid when recharging, but also to transmit it to external devices.

Properly equipped, an EV can power your home for one or more days, depending on the battery size and how profligate you are with your electricity use. In 2021, U.S. homes used 29 kWh per day on average. A base model F-150, with a 98-kWh battery, could keep your home running for more than three days at that rate; a Nissan Leaf, with a 37-kWh battery, would run out of juice in less than a day and a half.

“Properly equipped” is the operative phrase, however; merely having bidirectional charging isn’t enough. For example, some “vehicle to load” EVs can support small devices and appliances, not your whole electrical panel.

The state Senate has passed a bill (Senate Bill 233) that would require all electric cars, light-duty trucks and school buses sold in California to support bidirectional charging by model year 2030. The bill is awaiting action in the Assembly Appropriations Committee.

Ryan Schleeter of the Climate Center, a Santa Rosa-based advocacy group, said it’s not hard to enable bidirectional charging on a car — it’s just a matter of upgrading the vehicle’s software. But connecting your car’s battery (and its direct current) to your house (which runs on alternating current) involves some extra equipment.

The simplest approach, Schleeter said, is to install a bidirectional charger instead of the standard one-way device. Those aren’t cheap; the least expensive one Schleeter has seen is a $1,500 model due later this year.

An estimated 46,000 Los Angeles County residences were still without power Sunday night, according to the L.A. Department of Water and Power

In addition to powering individual homes, fleets of EVs can be used to bring electricity to a community, Schleeter said. Trials are already underway; for example, the Cajon Valley Union School District plugs its seven bidirectional-charging electric school buses (which had been heavily subsidized by grants) into San Diego Gas & Electric’s power grid when the buses aren’t in use, helping to prevent outages when demand is at its peak.

Climbing EV sales means that an enormous amount of battery power on wheels is coming to California. Schleeter said that 8 million EVs are expected in California by 2030, representing 80 gigawatt-hours of power — 36 times as much as the state’s largest power plant can generate in an hour.

Longer-term solutions

Feinstein said reducing the demand for electricity is an important part of the solution.

“A well-insulated home is going to stay much, much cooler during a heat wave,” she said. “There are really good subsidies for insulation through programs that the electric utilities run.”

O’Brien-Applegate agreed. “The longest-term foundation is really going to be doing energy efficiency and weatherization work on your home,” he said, pointing to better insulation, windows and air sealing. “That doesn’t take any power, and it’s an investment that will pay for itself over time.

“It’s not directly a power-outage measure, but it does help a lot in those situations, and over the long term is very cost-effective.”

The California Energy Commission expects the state to receive more than $580 million from the federal Inflation Reduction Act for weatherization and energy efficiency rebates. The money isn’t available yet, however, because the federal and state rules for it have yet to be finalized.

About The Times Utility Journalism Team

This article is from The Times’ Utility Journalism Team. Our mission is to be essential to the lives of Southern Californians by publishing information that solves problems, answers questions and helps with decision making. We serve audiences in and around Los Angeles — including current Times subscribers and diverse communities that haven’t historically had their needs met by our coverage.

How can we be useful to you and your community? Email utility (at) latimes.com or one of our journalists: Jon Healey, Ada Tseng, Jessica Roy and Karen Garcia.