Is California about to lose its most beautiful train ride?

- Share via

The tale of California’s railroads is a tale of beauties and beasts.

The beasts are the muscle machines, the workaday haulers chuffing to and fro with the takings of forests and mines, fields and factories.

The beauties are the glamor routes, the passenger trains that, whatever shabbiness may have befallen their interiors, more than make up for it with the grandeur of what lies outside their windows.

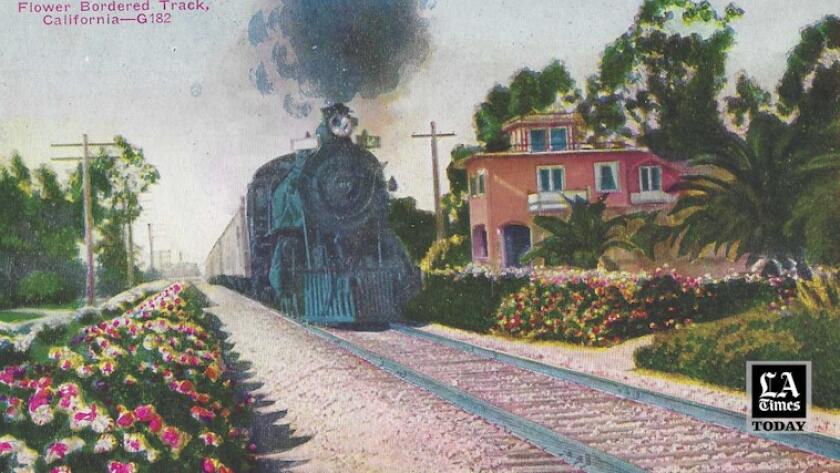

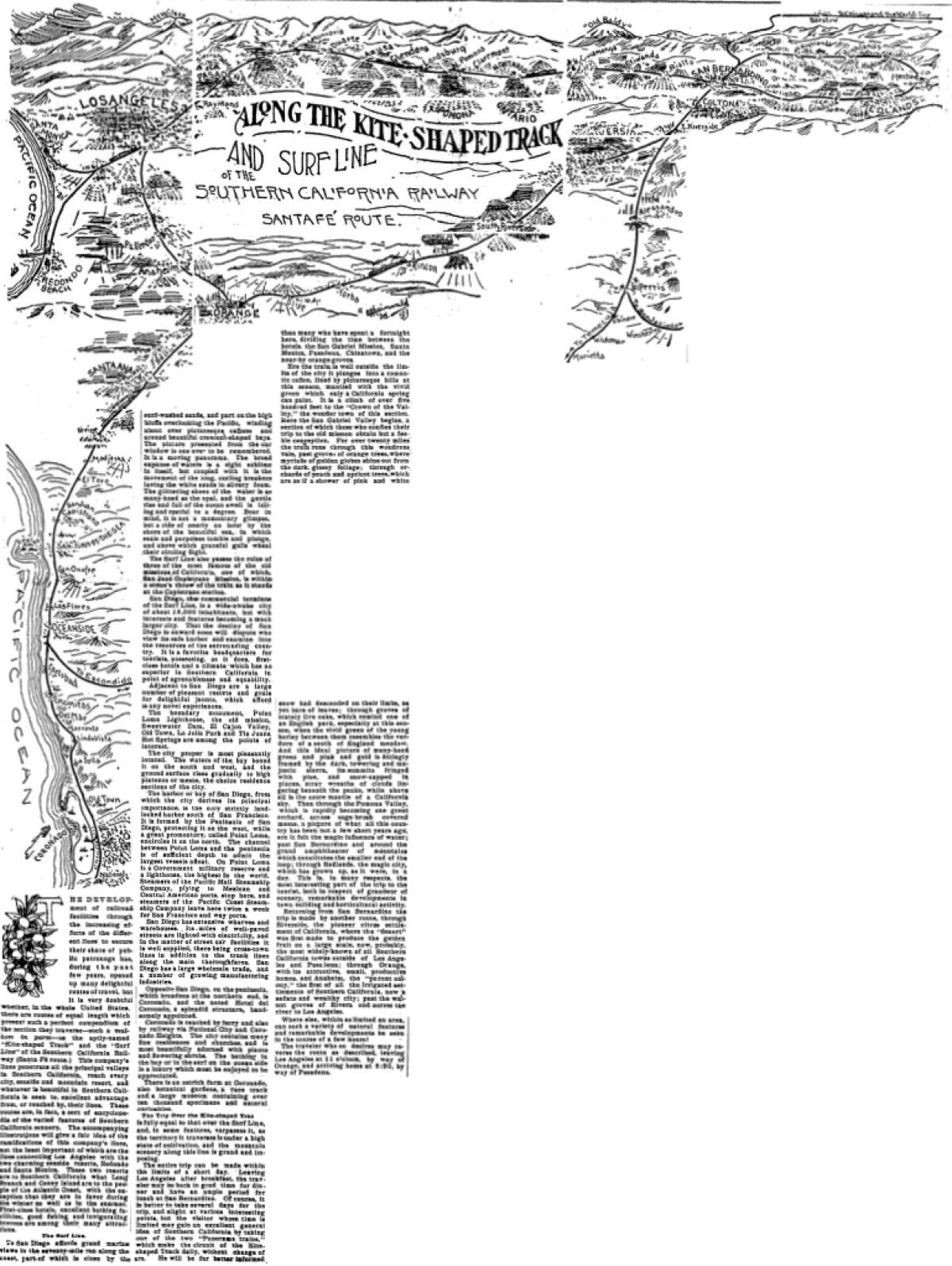

In 1882, not quite 15 years after the Golden Spike married the nation’s eastern and western rails, the enticing views of the California coast begat the “Surf Line,” starting with the National City-to-Oceanside route in San Diego County — one of the earliest of the lines that would be laid not just for getting passengers from points A to B, but from “aaah!” to “beautiful!”

President Lincoln, a-slog in the Civil War in the summer of 1862, was still farsighted enough to sign the Pacific Railway Act for building the transcontinental railway.

He did not live to ride aboard it. But he would have liked to; California was to him an El Dorado of prodigious promise and beauty, and he often spoke to the Sacramento Union correspondent Noah Brooks about moving here, “to afford better opportunities for his two boys.” At the White House, hours before he was assassinated, he bade farewell to House Speaker Schulyer Colfax, who was heading to California for his own journey. Lincoln told him upon their parting, “How I would rejoice to make that trip!”

Once Americans had supplanted plodding wagon trains with swift rail travel, the drama and the grandeur of the California coast were irresistible for railroads and passengers. By 1893, The Times was promoting the ocean and mountain vistas of the “kite-shaped” route aboard “panorama trains.”

But now — here’s that phrase that signals a change in fortunes — but now, what man hath joined by steel I-beams, climate change may put asunder. Along the gorgeous coastal rail ride through Orange and San Diego counties, the “Lossan” corridor train tracks are taking a pounding. (“Lossan” is brief for Los Angeles-San Diego-San Luis Obispo.) The bluffs are melting away like sand castles. The beach is receding like the Windsors’ hereditary hairline.

It’s an enormously popular route for commuters and leisure riders alike, as well as an indispensable corridor for moving freight. Anyone who’s been aboard knows there’s nothing as satisfyingly smug as flying along this rail route next to the frothy Pacific on a Sunday evening, and seeing miles of cars backed up on the 5 Freeway, trying to return home.

And still, humiliatingly, for almost 10 months now, the train service has been suspended off and on. At times the most scenic parts of the train route have been served by buses — buses! Some civic and transportation voices are saying perhaps the moment is here to move parts of the rail line inland, sacrificing beauty for safety and scheduling.

If it happens, it will have been a long time coming. The coast-flirting train lines have been beset by uncooperative nature almost from their inaugural runs. In the epochal storms of February 1914, the Lark — a swanky overnight train between Los Angeles and San Francisco — had to stop running for a time because of washouts, The Lark began in 1910 and made its last trip in 1968, by which time the commuter airline PSA had laid on a full schedule of commuter flights between Southern California and the Bay Area.

In March of 1906, a washout above Oceanside stranded about 150 northbound passengers. First a rescue ship tried to get them aboard in strenuous seas, but “the work of transferring the people to the [boat] was fraught with so great peril that after 18 had been dragged, wet and frightened, through the surf to the boat, the plan was abandoned.” The one hotel in town was taken over by the women passengers, and the men slept on the train, eating cream puffs and fudge for breakfast and dinner.

The peril has not always come from nature. Thirty years ago — and maybe even before and since — the boys of Carlsbad made a sport of defying death and the wrath of railroad law. They crouched on the wooden trestle’s inner rail and jumped away at the right moment as the train bore down on them. When the railroad put up fences to stop them, the boys tore them down and even dumped the debris on the tracks.

This country didn’t invent trains, but regards them as wholly American, from the plundering railroad robber barons of the Gilded Age to the notion that steel and steam can master a continent, no matter who or what had to give way. The great age of rail lasted until the greater age of the automobile, and the airplane, but even as we abandoned the train for our own wheels, we romanced it in our imaginations.

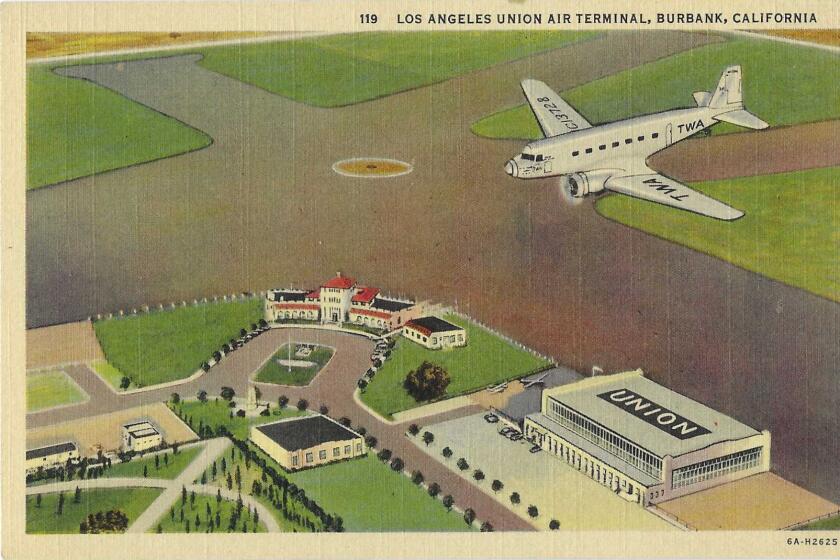

We still have lots of airfields, but gone from the landscape are the runways — near Griffith Park, near Wilshire and Western, in the Palisades — that could have challenged LAX for air superiority.

In 1978, Los Angeles County Supervisor Baxter Ward got his quixotic way: He persuaded the county and Amtrak to put eight 1940s railroad cars into regular service as the “El Camino,” along the San Diego-Orange County-L.A. run. It was called “El Camino” because, with some liberties, the path supposedly followed the camino, the route, of the mission-building Franciscan priest Junipero Serra.

Everyone professed to love the cars, and ridership took a happy 75,000-passenger bump. But it wasn’t enough to keep the old stock up and rolling, and six months later Amtrak put the cars into storage and put the modern “San Diegan” train cars back on the route.

Our excellent Times librarian Scott Wilson pointed out to me that the stories of coastal trains can be divided between the northbound from L.A. and the southbound from L.A.

Like many California trains, the San Diego-area Surf Line grew into its full length only by bits and fits, finally connecting San Diego to L.A. around 1888.

Fifty whole years later, the diesel-powered San Diegan, blurbed as the “first streamline train service” between the two cities, made its maiden voyage in March 1938. Curiously, there seemed to be no VIP or movie star ballyhoo; instead, as The Times wrote, the inaugural passengers on the north-to-south trip were 150 L.A.-area schoolkids.

In 1971, Amtrak took over the San Diegan, and around 2000 replaced it with the Pacific Surfliner, a train that — with asterisk exceptions for interruptions such as landslides — makes its way through Ventura and Santa Barbara into San Luis Obispo County, 350 or so miles in total, above and below L.A.

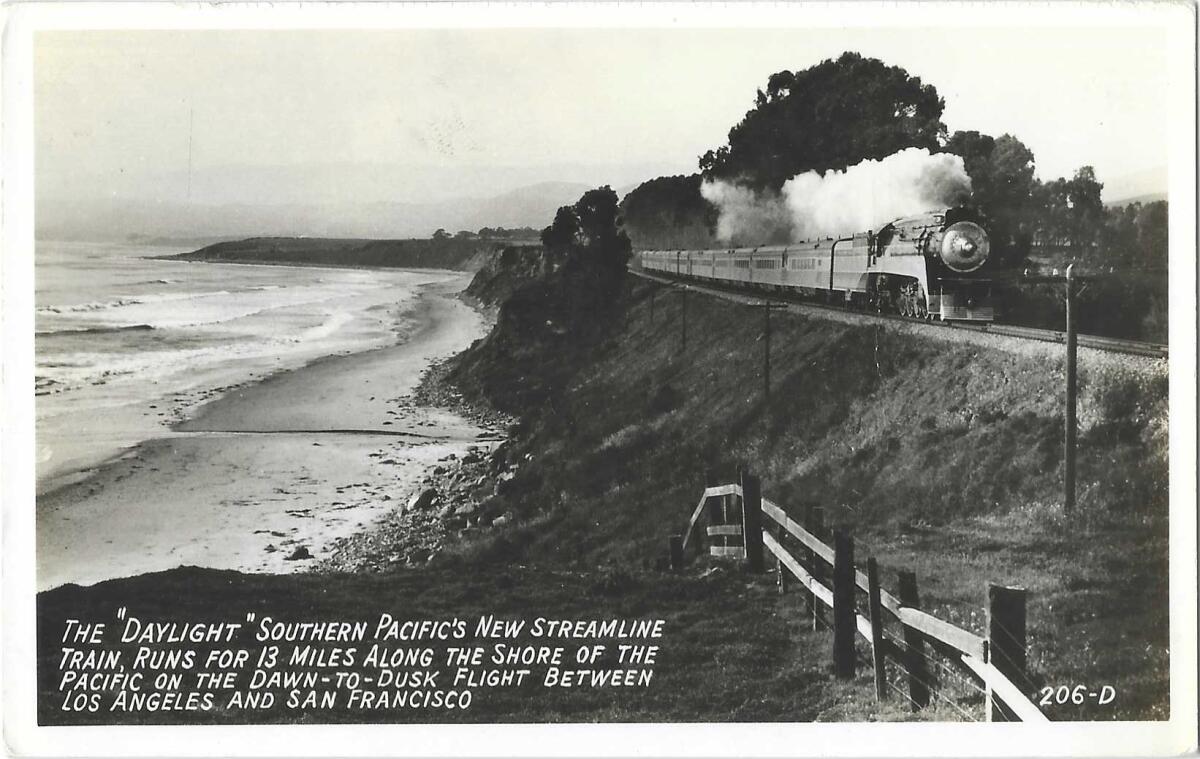

Railroads were nothing if not ambitious. Tracks and routes came together piecemeal — railroad buffs know these by heart, every bend and curve of track, every name change and route alteration. By 1922, the triumphant Daylight Limited service between Los Angeles and San Francisco offered travelers a short-order diner, open throughout its 13-hour trip.

The more streamlined version, the Coast Daylight, hit the tracks in 1937 and called itself, with reason, the “most beautiful train in the West,” and even “in America.” (In 1999, the “Daylight” got its own 33-cent stamp as part of a postal series of legendary American trains.)

Finally, in 1971, Amtrak took it over and it became the Coast Starlight.

Its day-and-a-half-long journey between L.A. and Seattle couldn’t hope to compete with the swiftness of plane schedules or the versatility of a car; the nickname “Coast Starlate” caught on for good reason. So in the 1990s, the Coast Starlight, for too brief a time, offered first-class culinary luxury unmatched even on the Orient Express, and a Vegas array of live music and comedians.

The food — local and regional delicacies, wine tastings to match — earned a rave review from a food magazine for such offerings as halibut in a pesto crust. On one trip in the early 2000s, The Times heard that the Dalai Lama had recently taken the Coast Starlight, with bodyguards and his own chef.

But again, in spite of the Coast Starlight’s popularity and loyal ridership, it had to pool its box office with the entire system, so its success could not save it, and the lavish deluxe trips and the train “experience” went back to the utilitarian.

One coastal train trip the railroads could never offer was a route along one of the most gorgeous pieces of earthly real estate, Big Sur.

Who is Griffith Park named for? What about Vasquez Rocks? The Broad? Mt. Baldy? Here are the namesakes of L.A.’s best-known landmarks.

The flighty Highway 1 through Big Sur has been vulnerable to the elements since it opened in 1937, and storm damage shut down its trickiest section in January (that bit is unlikely to open until the end of summer). The manager of Deetjen’s Big Sur Inn told SFGate that “we’re America’s most beautiful cul-de-sac right now,”

When a narrow asphalt thread of highway can barely cling to the Big Sur cliffs, a railroad — even a narrow-gauge railroad — would have been logistically impossible and environmentally catastrophic. The best the train can do is to deliver you to a car rental company in San Luis Obispo or Salinas, wish you luck, and await you in the Bay Area to connect up for the rest of the ride north.

Now, back to the frayed Southern California coast, and the fortunes of its surf-skirting trains.

If we must abandon the trains’ coastal beauty trips for sturdier railbeds inland, the least that the disputed new technology of AI can do for us is to give train riders traveling through scrub and subdivisions a real-time virtual reality cruise along the old surf-and-shoreline route.

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

- Share via

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.