A lot of what you’ve heard about affirmative action is wrong

The U.S. Supreme Court ruling striking down affirmative action in college admissions is certain to ripple across higher education for years. Debate in the lead-up to the court’s decision has ignited passions about accessibility, fairness and merit in the complex admissions process — and stirred up some misconceptions about affirmative action.

Educators worry about how they will continue to bring in a racially diverse student body — and how to pay for the costly measures to do so — now that it is illegal to consider race in admissions decisions.

In another major reversal, the Supreme Court forbids the use of race as an admissions factor at colleges and universities.

Common misunderstandings about the role and practice of affirmative action include:

Affirmative action uses racial quotas

Not correct. The U.S. Supreme Court struck down the use of racial quotas in a 1978 ruling involving Allan Bakke, a white man who was rejected twice for admission to UC Davis medical school even though he had higher grades and test scores than students of color who were admitted. The court also ruled, however, that race could be used as one of several factors in college admissions to create a diverse class.

Affirmative action only benefits students of color

Not according to research. Affirmative action helps create diverse classes, and years of research have shown that students of all races and ethnicities benefit from that diversity with higher levels of social, emotional and cognitive skills, including critical thinking and problem solving. Experiences with diversity also help careers: In one study of major employers, 96% said it is “important” that employees be “comfortable working with colleagues, customers, and/or clients from diverse cultural backgrounds.”

Affirmative action keeps qualified Asian students out of top schools

It’s hard to know why students are accepted or rejected by top colleges because their admissions process is usually shrouded in secrecy. But Asian Americans make up the largest share of students of color at most selective institutions — disproportionately so — including those that use affirmative action. At Harvard University, for instance, Asian Americans make up 20% of undergraduates, followed by Latinos at 12% and Black students at 9%, according to the federal College Scorecard’s latest update, in April 2023.

At USC, Asian Americans make up 24% of undergraduates, with Latino students at 17% and Black students at 6%.

The U.S. Supreme Court hearings on affirmative action this week highlighted widespread fears among Asian Americans that they face bias in selective college admissions.

Asian Americans also make up the largest demographic group at the University of California, and that share has not appreciably changed since the 1996 passage of Proposition 209, which outlawed the use of race and gender in public education, employment and contracting. Asian Americans made up 35% of first-year UC students in 1995, before the ban, and also in 1998, the first admission year after it took effect. That figure grew to 38% in fall 2022, UC data show. At UC, the number of Black and Latino students declined after the Proposition 209 ban but has since risen to exceed the previous levels.

Highly qualified students of all backgrounds are routinely rejected by elite institutions because of the scarcity of seats. UC Berkeley Chancellor Carol Christ has often said her campus could fill every seat with straight-A students but simply doesn’t have room for all of them.

Most colleges and universities across the country use affirmative action

Not true. Higher-education experts say a small number of highly selective institutions consider race in admissions.

Among 1,364 four-year institutions in the country, only 17 admitted fewer than 10% of applicants — including Stanford, Harvard and Yale — and 29 accepted between 10% and 20%, including USC, UCLA and UC Berkeley, according to a 2019 Pew Research study.

These elite schools do not reflect higher education as a whole: They account for just 3.4% of colleges and 4.1% of students. They use affirmative action to advance their missions valuing diversity and opportunity for students of all backgrounds.

In reality, experts say, most institutions accept most students who apply — which means they don’t need to use race as a factor to apportion seats. Rather, they mostly look at grades and transcripts to evaluate whether the applicants have a good chance of succeeding, experts said.

Affirmative action is the main competitive edge, the ‘hook’ for college admissions

Not true. Academic performance — grades, test scores, rigor of high school transcript — is by far the most important criterion in college admissions. Among other factors, admission preferences for “legacies” — children of alumni — are widely used, with 787 colleges and universities reporting in 2020 that they provided these applicant preferences, according to a fall 2022 report by Education Reform Now, a nonpartisan, nonprofit think tank. The practice is most common among private colleges in the Northeast, the report found.

In anticipation of the Supreme Court ban on affirmative action, such birthright preferences have come under increasing scrutiny as an unfair advantage that rewards predominately white applicants. Experts predict it will be harder for colleges to defend legacy admissions after the affirmative action ban.

The Supreme Court’s ban on affirmative action has triggered angst on campuses about how to promote diversity without considering race in admissions decisions.

The Pew survey showed that nearly three-quarters of Americans believe that whether a relative attended the school should not factor into admissions decisions.

In California, Caltech and Pomona College have ended legacy preferences. The University of California does not consider family relations in admissions.

Without affirmative action, the numbers of Black and Latino students will plunge

That could happen, but it doesn’t have to.

Colleges have had a long time to prepare for the Supreme Court decision. Many campus leaders, bracing for this outcome, say robust recruitment and academic preparation programs in underserved communities of color could help bolster enrollment numbers. Such work is costly and it’s unclear whether there is the financial and political will to sustain such admissions programs.

The California experience is instructive.

The number of Black and Latino first-year students plunged by nearly half at UCLA and UC Berkeley during the first admission year under Proposition 209.

Since then, UC campuses have made strides. Black and Latino students increased to more than 43% of the admitted first-year class of Californians for fall 2022, compared with about 20% before Proposition 209. For the third straight year, Latinos were the largest ethnic group of admitted students at around 37%, followed by Asian Americans at 35%, white students at about 19% and Black students at a little under 6%.

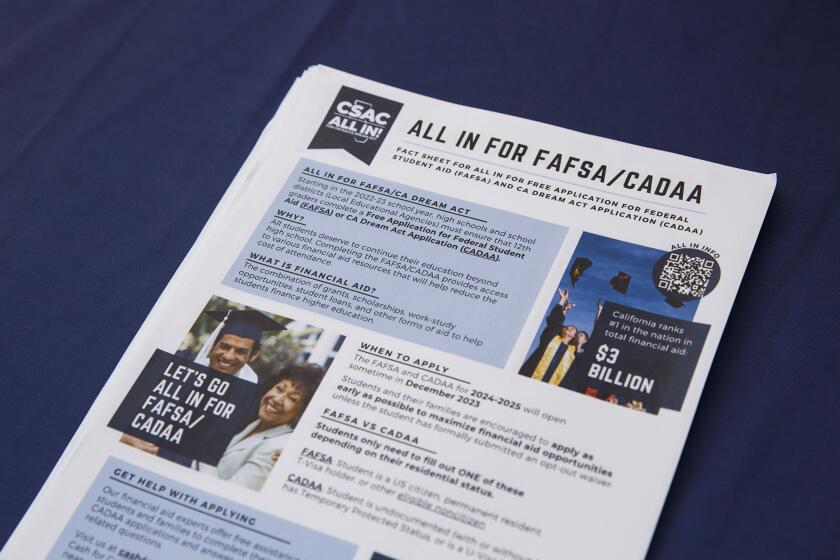

UC increased diversity using such race-neutral measures as outreach to communities with lower income and parental education levels — spending a half-billion dollars over two decades on the efforts. It has not entirely succeeded in enrolling students who fully reflect the state’s ethnic and racial makeup, but has made meaningful progress toward that goal.

California voters support affirmative action

Even in blue California, as recently as November 2020 voters said no in big numbers to affirmative action. Proposition 16 — placed on the ballot by the Democratic-controlled California Legislature — would have repealed Propostion 209. But it was rejected by more than 1 million votes.

Proposition 16 was endorsed by the UC Board of Regents, all 10 campus chancellors and major student organizations, which blamed the 27-year statewide ban on affirmative action for particularly hurting Black and Latino enrollment.

Prop. 16 faced an uphill challenge, hobbled by a truncated campaign and the pandemic, which made voter outreach difficult.

But polls by UC Berkeley’s Institute of Governmental Studies and the Public Policy Institute of California showed that Latino voters in California — who account for roughly a quarter of the electorate — were evenly split. White voters were firmly against the measure, while Black voters were strongly in favor.

The Supreme Court ruling will bring big changes in California

Admission preferences based on race already are illegal in California for public universities. So nothing will change there — except that there could be no future efforts to restore these preferences at the ballot box.

However, more than 80 private institutions in the state had been free to consider race in admission decisions prior to the Supreme Court ruling. That will no longer be possible.

Times staff writer Phil Willon contributed to this report.