These 33 important buildings owned by L.A. County could be at risk in a major quake

- Share via

For six decades, a boxy downtown building has been the beating heart of Los Angeles County government — home to the five supervisors, half a dozen departments and hundreds of employees who filter through its halls each week.

For just as long, the Kenneth Hahn Hall of Administration has been vulnerable to collapse in the event of a major earthquake — one of 33 county-owned concrete buildings determined to be potentially at risk, county records show.

Many of the facilities house officials who would be critical to steering the county through an emergency. In addition to the Hall of Administration, they include the Department of Medical Examiner-Coroner, where autopsies are performed, and the headquarters for the departments of public health and health services, which house some of the two departments’ top officials downtown.

The list was provided to The Times as the county embarks on a landmark effort to identify and protect its stock of so-called non-ductile concrete structures from collapse in earthquakes. Last month, the Board of Supervisors set an ambitious 10-year deadline for officials to complete seismic upgrades on them — an undertaking that experts estimate will probably cost hundreds of millions of dollars.

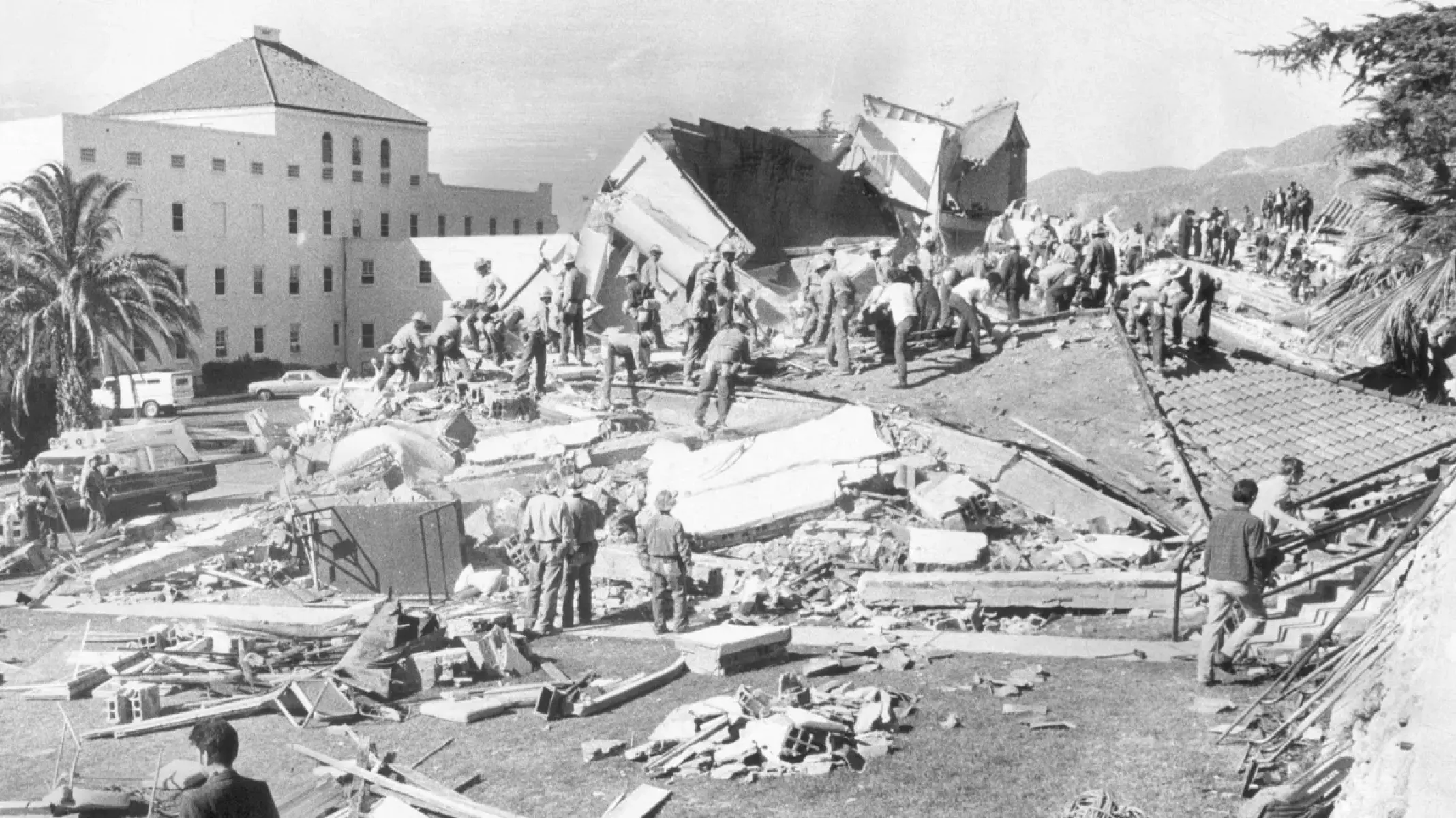

Non-ductile buildings have an inadequate configuration of steel reinforcing bars, which allows concrete to explode out of columns when shaken in an earthquake, a prelude to a catastrophic collapse. This flaw, now well known, was discovered in the 1971 Sylmar quake.

The vast majority of structures on the county’s list were built during the post-World War II boom, when many concrete-frame buildings were erected with the potentially fatal flaw that can cause the same type of catastrophic collapse seen in the recent magnitude 7.8 earthquake in Turkey and Syria.

Illustrations show how concrete can explode out of a column when shaken, triggering a building collapse, if the configuration of steel reinforcing bars inside is inadequate.

Experts said it is essential that these buildings be able to withstand a future major earthquake, which would be vital to local government’s ability to function when Southern California is hit by a quake of comparable magnitude — something that last occurred more than 160 years ago.

“Autopsies! Do you think you want the coroner to be able to work after the earthquake?” said seismologist Lucy Jones, a research associate at Caltech.

Heavy damage or collapse could not only cause injuries and deaths, but also hobble emergency response and force closures of neighboring buildings overwhelmed by a massive debris zone.

“After an earthquake, you want your public health director to be able to do her job. You want the coroner to be able to do his job. And you want the county supervisors to be able to get together and make decisions and not be having to deal with their own trauma, with their own staff being injured,” Jones said.

Most of the 33 buildings are in the Los Angeles Basin, which has been spared the strongest shaking of L.A. County’s two most destructive earthquakes since World War II — the magnitude 6.6 Sylmar earthquake of 1971 and the magnitude 6.7 Northridge earthquake of 1994.

The strongest shaking from both of those earthquakes was centered north of the basin, in the San Fernando Valley. The majority of the buildings were built in the 1960s and 1970s, with a handful built in the first half of the 20th century. The oldest building on the list — now a pharmacy service building for L.A. County-USC Medical Center — was constructed in 1917, according to the list.

A magnitude 7.8 earthquake — which last hit Southern California in 1857 — would produce 45 times more energy than the Northridge earthquake and cause strong shaking across a much wider zone of Central and Southern California.

The list includes the Kenneth Hahn Hall of Administration, the center of Los Angeles County government.

In contrast to the San Fernando Valley, many buildings across the L.A. Basin have never experienced particularly severe shaking since they were built. The fact that these concrete buildings have survived prior earthquakes does not mean they would survive the next one, experts say.

“We do know that there is seismic risk all over Southern California, and we’ve seen — and we saw again in Turkey — that that construction type does not perform well when subjected to strong shaking,” said structural engineer David Cocke, former president of the Earthquake Engineering Research Institute. For communities to recover after a big earthquake, such essential buildings “need to be up and running.”

Vanessa Moody, senior manager with the county Chief Executive Office’s Capital Programs Division, said the county began a two-year review in 2019 of its buildings in need of a seismic retrofit.

In 2021, structural engineering firms came back with the list of 33 potentially vulnerable county-owned concrete buildings. A spokesperson for L.A. County Public Works said the list does “not indicate a specific level of earthquake damage risk” and identifies structures that were built before 1978, are multistory and are classified as a non-ductile concrete building.

They include Pitchess Detention Center East Facility in Castaic, a jail where 36 inmates were housed as of earlier this month; clinics in South L.A., downtown and Hollywood; fire stations in Inglewood and West Hollywood; and libraries in Compton, Huntington Park and Montebello.

The board unanimously passed a motion ordering officials to prepare new rules that would require non-ductile concrete buildings owned by the county, as well as any in unincorporated areas, to be retrofitted. Once the new rules go into effect, building owners would have 10 years to complete the retrofits.

Many of the buildings in need of seismic upgrades are hubs for health services. The list includes numerous buildings surrounding Los Angeles County-USC Medical Center, the county’s flagship public hospital in Boyle Heights.

The main hospital itself is new, housed in a building opened in 2008 that replaced the landmark Depression-era General Hospital, which is mostly mothballed and could be reconfigured into a homeless and affordable housing building after a seismic retrofit. State law requires hospitals to be seismically robust to ensure their doors can remain open to patients after a major earthquake, with a deadline of 2030.

Once considered politically impossible because of cost, requiring owners to retrofit their buildings gets overwhelming support from L.A. residents.

But that state law does not require nearby buildings to be seismically sound, meaning parking structures and clinics surrounding major hospitals may be vulnerable.

Among those at possible risk is a parking structure, known as Lot 12, for County-USC’s doctors, patients and visitors; and two buildings on Griffin Avenue that are home to the Violence Intervention Program, a partnership between the county and a nonprofit mental health provider that operates the largest child abuse program in the nation. Among the buildings potentially at risk is the Santana House, named for the musician Carlos Santana and his former wife, Deborah, who have financially supported the Violence Intervention Program.

Dr. Astrid Heger, director of the Violence Intervention Program, said the county informed her on Wednesday that there was concern about the structural integrity of the buildings the program uses. She said she has already identified a civil engineer — independent of the county — who will assess them.

Heger said she’s concerned about the pace at which the county would actually complete the retrofit, and has already told officials that if a retrofit is needed for the Griffin Avenue buildings, she is prepared to find the funds independently to get the seismic strengthening done as quickly as possible.

“We will pay to have it retrofitted. We’ll raise the money. To be honest with you, we cannot take any risks here at all. The county moves really slowly,” Heger said. “We want to make sure we are ahead of anything that could be potentially dangerous for our patients and our staff.”

After The Times told Heger the county was aware in 2021 of her buildings being potentially at risk in an earthquake, she said she was “surprised that we are learning about it this late in the process.”

Heger said she has raised millions of dollars to renovate the two county-owned buildings on Griffin Avenue, which opened in 2003 and 2007, but this was the first she had heard of the possible seismic risk. “I’m basically disappointed that I wasn’t given the opportunity to address this issue much sooner,” Heger said.

A major earthquake would take a severe toll on the mental health of the community.

“And in a mental health crisis in the county of Los Angeles, putting the largest provider out of whack would be devastating,” Heger said.

Michael Wilson, a spokesperson for the county’s Chief Executive Office, said the Department of Health Services was notified in January 2022 of all its buildings on the list, and that the office has been working with the department since then on next steps.

“The buildings on the compiled list are not in imminent danger but included because they meet established criteria for retrofitting,” he said. “The county is methodically working on approaches to complete the retrofits as expeditiously as possible.”

Another important building possibly vulnerable to earthquakes is the County-USC Outpatient Clinic building, also known as Outpatient Building B, built in 1963. The Violence Intervention Program shares space in that building that serves as a forensic clinic of victims of sexual assault and child abuse, cares for elder abuse patients and screens children who may have been prenatally exposed to alcohol.

The site is also home to clinics for high-risk teenagers and children with chronic medical illnesses, including one focused on LGBTQ youths known as the Alexis Project.

The public works department is expected to ask the board to vote soon on a three-year, $35-million consulting contract to design seismic retrofits for the 33 buildings.

Moody said retrofitting designs are already underway for three of the buildings: the Hall of Administration, the Department of Medical Examiner-Coroner in Boyle Heights, and Ferguson Administrative Services Center in Commerce, the hub for administrative services for the public health and health services departments.

The county had started designing seismic upgrades for these three buildings before the board’s motion, Moody said. The county has allocated $134 million for the designs and preconstruction work — $95 million for the Hall of Administration and roughly $40 million for the two others, she added.

L.A. County’s proposed earthquake rules would require certain older concrete buildings in unincorporated areas, and those owned by the county, to be retrofitted.

But Moody said the county hasn’t yet started planning for the 30 other buildings on the list, which include the downtown home to the offices of the county’s top health officials, Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer and Health Services Director Dr. Christina Ghaly.

The Department of Health Services runs the nation’s second-largest municipal healthcare system and operates four hospitals: Los Angeles County-USC Medical Center, Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, Olive View-UCLA Medical Center and Rancho Los Amigos National Rehabilitation Center.

Officials have not yet decided which to tackle first, nor do they have a cost estimate, Moody said, adding, “We’re not there yet.”

The county has already completed retrofits to the Hall of Justice — which houses employees of the Sheriff’s Department and district attorney’s office — and Bob Hope Patriotic Hall downtown, home of the county Department of Military and Veterans Affairs, as well as the L.A. County Public Works headquarters in Alhambra.

“The motion that passed was not the first by any means,” Moody said. “This has been going on for over a decade.”

The cities of L.A., West Hollywood and Santa Monica require non-ductile concrete buildings within city limits to be retrofitted, with deadlines ranging from 2027 to the 2040s.

Several non-ductile concrete buildings on the county’s list are on the campus of Martin Luther King Community Hospital in Willowbrook. They include the Leroy Weekes Medical Support Building North, the Service and Supply Building South, and the Interns and Residents Building, which contains a 100-bed recuperative care unit.

Also at possible risk are the Hall of Records in downtown; two Department of Public Social Services buildings in South L.A.; a parking structure for the Eastlake Juvenile Courthouse; and the administrative headquarters of the county Internal Services Department in East L.A., which offers support to other county agencies in areas like contracts, purchasing and information technology.

After the 1971 Sylmar earthquake, non-ductile construction was deemed so unsafe that it was banned in future buildings by the 1980s. But most local governments have done little to order older buildings be evaluated and strengthened if found to be deficient.

Forty-nine people died in the 1971 collapse of the Veterans Administration hospital in Sylmar, and three were killed when the newly built Olive View Medical Center saw buildings and stairways collapse, lurch or topple. A Kaiser Permanente office and clinic and a Bullock’s department store partly collapsed in the 1994 Northridge earthquake.

The same type of non-ductile flaw led to the collapse of freeways in the Sylmar and Northridge earthquakes and the 1989 Loma Prieta quake in the San Francisco Bay Area.