Odds of El Niño returning to California are increasing. Would it bring even more rain?

- Share via

The stubborn La Niña climate pattern that gripped the tropical Pacific for a rare three years in a row is waning, and the odds of an El Niño system forming later this year are getting stronger, according to recent meteorological reports.

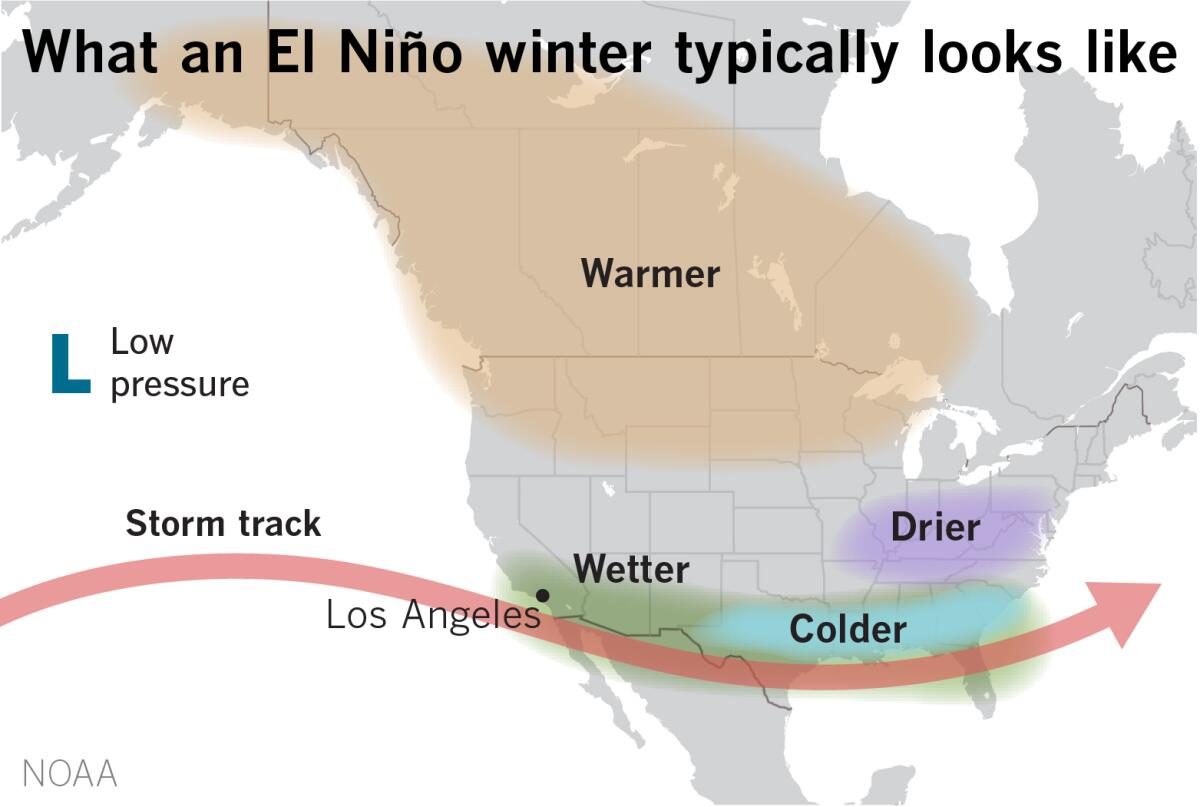

The El Niño-La Niña Southern Oscillation, sometimes referred to as ENSO, has a major influence on temperature and rainfall patterns in different parts of the world, with La Niña often associated with drier-than-normal conditions in California, especially the southern part of the state.

El Niño, on the other hand, is linked to an enhanced probability of above-normal rainfall in California, along with accompanying landslides, floods and coastal erosion, though it is not a guarantee.

The latest outlook from the World Meteorological Organization says there is a 90% chance of a return to “ENSO-neutral” conditions from March to May, with that probability decreasing as the summer goes on.

That decrease “can be seen as a potential precursor for El Niño to develop,” with a 35% chance of El Niño developing from May to July, the agency says.

Longer-lead forecasts show an even stronger chance of El Niño developing from June to August — 55% — though the forecasts are “subject to high uncertainty associated with predictions this time of year.”

The snow-capped Sierra Nevada and the Santa Monica Mountains north of Malibu are among the areas of California no longer considered to be in drought.

The forecast is worth keeping an eye on. In the winter of 2015 and 2016, one of the strongest El Niños on record contributed to high wave energy along the West Coast and record coastal erosion on many California beaches. That winter also saw a record-breaking hurricane season in the central North Pacific, significant drought in the Caribbean and one of the globe’s hottest years on record.

A similarly strong El Niño in the winter of 1997-98 saw powerful precipitation in California, including a series of storms that ended with 17 deaths and more than half a billion dollars of damage in the state.

And in the winter of 1982-83, El Niño was linked to near record-setting precipitation in the northern Sierra and one of the state’s costliest flood seasons in decades, including decimated piers and thousands of damaged homes.

The system can also fuel warmer conditions around the world, WMO Secretary-General Petteri Taalas said in a statement.

“La Niña’s cooling effect put a temporary brake on rising global temperatures, even though the past eight-year period was the warmest on record,” Petteri Taalas said. “If we do now enter an El Niño phase, this is likely to fuel another spike in global temperatures.”

California’s deadly storm season continued Friday as the first of two atmospheric river storms descended on the state, prompting evacuation orders.

David DeWitt, director of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Climate Prediction Center, said the WMO forecast largely aligns with predictions at the federal agency.

But El Niño and La Niña are not the only factors that drive global and regional climate patterns, he said, as evidenced by the notably wet winter in California this year, which defied expectations of a drier-than-normal season driven by La Niña.

The uncommon “triple dip” of La Nina marked the first time in the 21st century that the system appeared three years in a row, but the system began weakening around the end of December.

Around the same time, another pattern known as the Madden-Julian Oscillation moved in, signaling strong precipitation, DeWitt said. The eastward-moving disturbance of clouds, rain, wind and pressure often manifests as anomalous rainfall.

In fact, while El Niño-La Niña accounts for climate variability on a seasonal timescale — three months or longer — the Madden-Julian Oscillation often drives sub-seasonal weather within that larger frame. The NOAA likens the systems to bicycles: If ENSO is a stationary bicycle in the middle of a stage, the Madden-Julian Oscillation is like a bike rider “entering the stage on the left and pedaling slowly across the stage, passing the stationary bike (ENSO), and exiting the stage at the right.”

For decades, El Niño seemed synonymous with wet winters for Southern California, while La Niña was a heralder of drought. But the would-be model didn’t hold up this winter.

DeWitt said very active Madden-Julian Oscillations this season brought “a lot of atmospheric river activity, as well as even some more traditional types of storms that don’t necessarily tap the tropical moisture.”

“It’s really been this active MJO, or Madden-Julian Oscillation, that has resulted, essentially, in an above-normal precipitation signal for the Southwest U.S., especially California, as opposed to the below-normal precipitation that you would expect associated with La Niña,” he said.

In other words, while the appearance of El Niño later this year could indicate wetter than normal conditions, there are other factors that could overcome it. Unfortunately, while forecasters have some ability to predict El Niño and La Niña in advance, the best lead time for Madden-Julian Oscillations is only a few weeks, DeWitt said.

And while some states, such as Florida, are more reliably affected by ENSO, it’s responsible for only about 10% to 20% of seasonal variability in California, DeWitt said. “So that means El Niño-La Niña doesn’t explain 80% of the winter precipitation in California.”

The La Niña climate pattern, which tends to bring dry conditions to the Southwest, is expected to persist for another year amid the ongoing drought.

“El Niño-La Niña does give us some useful information,” he said, “but its important to recognize what the limits of that information are.”

Times staff writer Rong-Gong Lin II contributed to this report.