As a reporter, I’d braced myself to cover mass shootings. My first was in my own community

He was walking by himself, in no particular direction. Then the corner of his eye caught the sun and glinted for a moment — an unfallen tear.

My colleague had approached him, asking if he lived nearby. He shook his head, replied, “No” and kept moving.

“Would you mind if I tried talking to him?” I asked, and she urged me on. It was Jan. 22, and we were in Monterey Park the day after a mass shooting had stolen the lives of 11 people, devastating a mostly Chinese community in the process.

I ran after him and then I stopped, watching as he trained his eyes on my face, analyzing my features. I introduced myself in Mandarin and told him I was a reporter for the Los Angeles Times. Could I ask a few questions about the shooting?

He may have nodded yes, so I started in.

“Do you live around here?” I asked.

He pointed to the house right behind us — a pale yellow, single-story home with white blinds. He could hear the American accent in my voice and switched to English. He told me he hadn’t been home at the time, but his mother was, and she heard what she thought were firecrackers in the distance. They lived near Star Ballroom Dance Studio, he said, where the shooting took place.

I asked if he’d known anyone who had been dancing at the studio, if he knew anyone who had been there that night. He wiped his face and said no, he didn’t know much about it.

“Are you Chinese?” he asked.

“I was born here,” I said, “but my parents moved here from China.”

“ABC,” he said with a hint of a smile. “American Born Chinese. Just like my daughter.”

Right before we parted ways, he told me his American name was Ben.

I’d been asleep when my editor called at 11:20 p.m. It was the eve of Lunar New Year. When I called him back, he picked up on the first ring. There had been a mass shooting in Monterey Park, he told me, with as many as 10 people killed.

Could I go to the scene?

I threw on whatever clothes were closest and quickly looked up the news of the shooting on my phone. When the reports mentioned Monterey Park, most of them added that it was “known as the first suburban Chinatown.”

My heart sank.

During the 17-minute drive, every scenario bounced around in my head. I thought of the Atlanta spa shootings and the spate of anti-Asian hate crimes at the height of the pandemic. During that time, I carried around pepper spray and wore sneakers, hoping I might have a shot at outrunning a potential attacker. I’d never had any interest in martial arts, but I started tagging along with my boyfriend to his self-defense classes.

I stayed on the scene with several other reporters for hours, speaking to nearby residents, business owners and even one person whose younger sister had been at the dance studio during the shooting. When I woke up later that day, police had confirmed that 10 people were killed (another would die in the hospital of injuries from the shooting) and that the suspected gunman was a 72-year-old Asian man.

I looked up his photo online.

My first thought was that he could be my grandfather.

The timeline of my generation is littered with mass shootings. When I was in sixth grade, a survivor of the Columbine High School massacre visited my middle school to give a presentation during an assembly. The Virginia Tech shooting happened a year later; a friend’s brother attended the Blacksburg, Va., school, and it felt personal.

When I was a freshman in college, a gunman opened fire at Sandy Hook Elementary School, killing more than 20 schoolchildren and staff members. A month after I graduated, nearly 50 people were fatally shot at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, Fla. A few months before I started as a reporter at the Mercury News, 10 people were killed at the Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority rail yard in San Jose.

As a journalist in the U.S., I knew covering a mass shooting was a matter of when, not if. I had braced myself for the possibility that I might be covering shootings at music festivals, concerts, movie theaters, nightclubs, churches and big-box stores, shootings where the perpetrator was usually a man with a gun.

It never occurred to me that the first mass shooting I covered would take place in my community.

The 48 hours after that first call were a blur. I knocked on doors and stopped people on the street, introducing myself in Mandarin. I saw the flicker of recognition when they looked at my Chinese face, followed by a wall of detachment when I explained I was a journalist hoping to ask them about the shooting.

Some people waved me away, saying they weren’t at the dance studio that night and didn’t know anyone who had been. Others emphasized that this was supposed to be a “safe” city, that they’d never heard of any shootings in Monterey Park before Jan. 21.

Some part of me felt guilty — that I was intruding on this once-quiet and private community, and the people who agreed to speak with me were sharing their stories only because I was one of them. When I had finished a particularly tough interview with a survivor and thanked her for her time, she responded in Mandarin: “Méi wèntí. Wǒmen dōu shì péngyǒu.”

“No problem, we’re all friends.”

Hearing that made me want to cry.

Later, I asked the dance instructor who had helped me set up the interviews if he believed that talking about what happened was cathartic for the survivors.

“Are we helping these people or are we making their lives worse?” I asked, more to myself than to him.

“I don’t know,” he replied. “I’ve been wondering the same thing myself.”

I was torn. I wanted to give the survivors and the family members of the victims space and time to heal on their own. I knew that many of them, particularly those in the older generation, were uncomfortable speaking with the press.

I wanted to treat them with as much compassion and sensitivity as possible, to let them know that they were more than a headline, that their community should be singled out for more than this tragic event. I felt a duty to portray the survivors as individuals with backstories just as rich as my grandparents’.

During the late 1990s, my mother’s parents emigrated from China to my small hometown in Pennsylvania, about 40 minutes from Philadelphia. They didn’t know anything about the U.S. and felt safest and most comfortable in their home country. But when my mother asked them to help take care of my sister and me, they came without question.

My grandparents were the ones who took care of me after school, who cooked me tomato egg with rice, who taught me how to count to 10 and how to tell time in Mandarin.

They barely spoke any English. When some of the neighborhood kids would knock on my door to ask if I could come out to play — or to just say hello — my grandmother would shake her head and tell them in Mandarin that she couldn’t understand them. Then she would close the door.

There were almost no other Chinese people in my town, and they were homesick, yearning to be with people outside of our family who spoke Mandarin and ate their same food. When my English proficiency surpassed my Chinese, I started to feel guilty that my ability to communicate with them was declining.

I also started to realize that even though we spent so much time together, I didn’t know much about my grandparents. They rarely shared anything personal. Years after my grandmother had passed away and my grandfather had moved back to China, I finally learned — through my mother — that my grandmother had once been a professor.

When I spoke with the family members of the victims and the survivors of the shooting, I saw their faces. I saw them as a door was closed and hands waved me away. I saw them in the face of the gunman, and wondered if social isolation or the crush of loneliness could have driven him to commit such a heinous act.

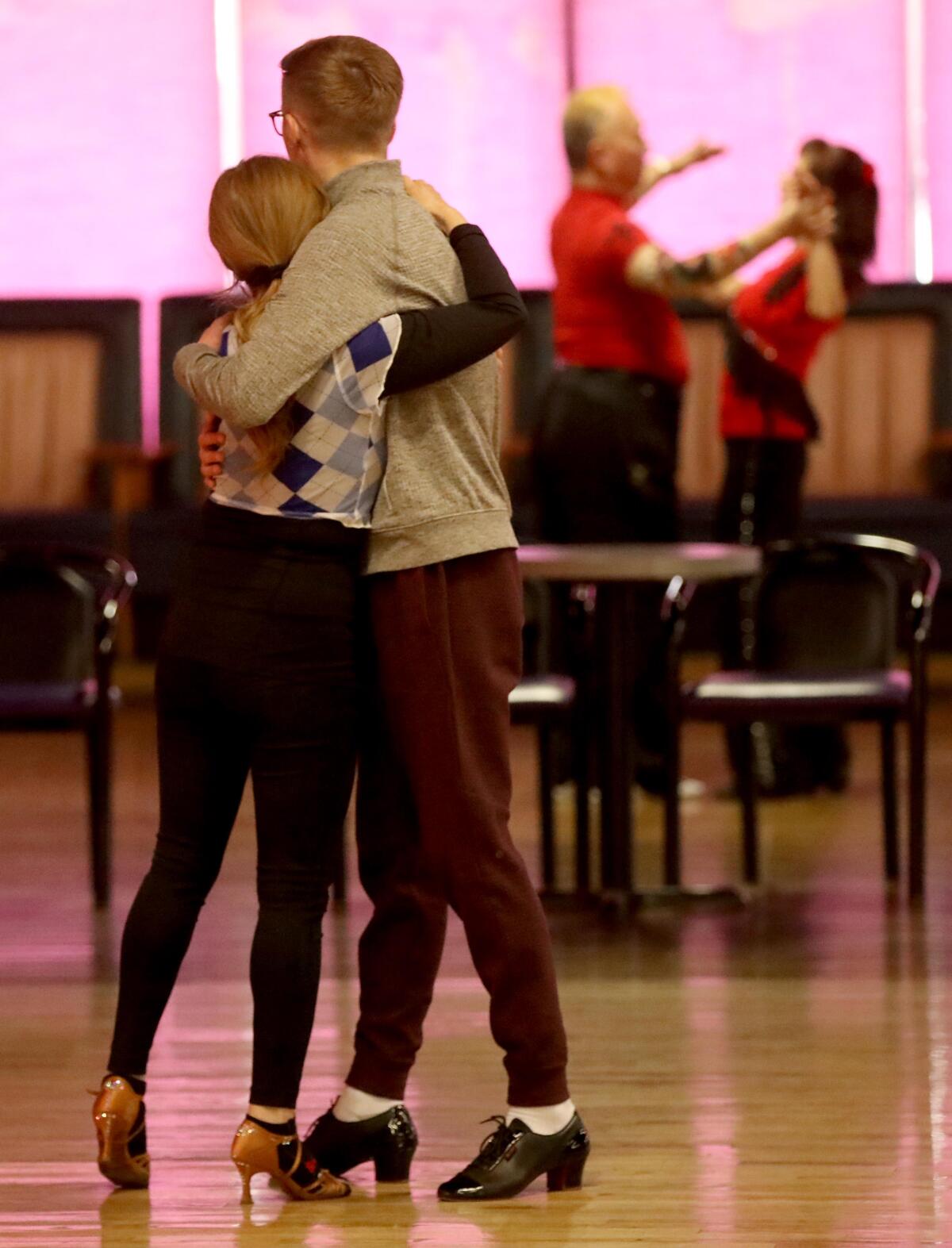

I also saw their faces as I attended vigils for the victims and heard residents speak about how important Monterey Park was to them as an Asian enclave. My grandparents would have loved to have had a community like this one, a place where they could find the groceries that reminded them of home and all the store signs were in Chinese. A place where they could learn to dance with other people their age on the weekends.

My mother once told me that most Chinese immigrants, especially people in their 60s and older, just wanted to work, make new lives for themselves in the U.S. and keep quiet. They weren’t comfortable expressing their emotions. And, even if they’d wanted to, the language barrier typically isolated them from much of American society.

That contrasted sharply with my own experiences as an Asian American who was learning to address the stigma surrounding mental health issues in our community and to initiate difficult conversations about intergenerational trauma.

The inability to open up stayed with me as I continued to interview sources in an attempt to piece together what happened that night at Star Dance.

Some people appeared eager to tell me exactly how they had escaped the gunman. Others teared up as they recounted how longtime friends were shot and killed in front of them. I found myself crying along with many of them.

Most of all, my heart ached when survivors asked me not to use their last names, because they hadn’t told their own family they’d been at the dance studio that night. They didn’t want them to worry. If my grandparents had been there, they probably wouldn’t have told me either.