- Share via

For decades, Bosch Dairy in Ontario, where three generations raised cattle, was a bucolic outpost with fields of cows and rows of eucalyptus to cut the driving wind that came down the Cajon Pass.

A few years ago, Bud Bosch noticed semitrailers occasionally rumbling along the two-lane rural road by his property. Soon, dozens were kicking up dust, night and day, plying roads made for tractors.

Bosch thought he had escaped the explosion of warehouse development that has wiped out farmland and open space. But the ecommerce boom of the pandemic accelerated the land grab, and the region became ever more hardscaped into the staging point for trains and trucks carrying goods from the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach to the rest of the nation.

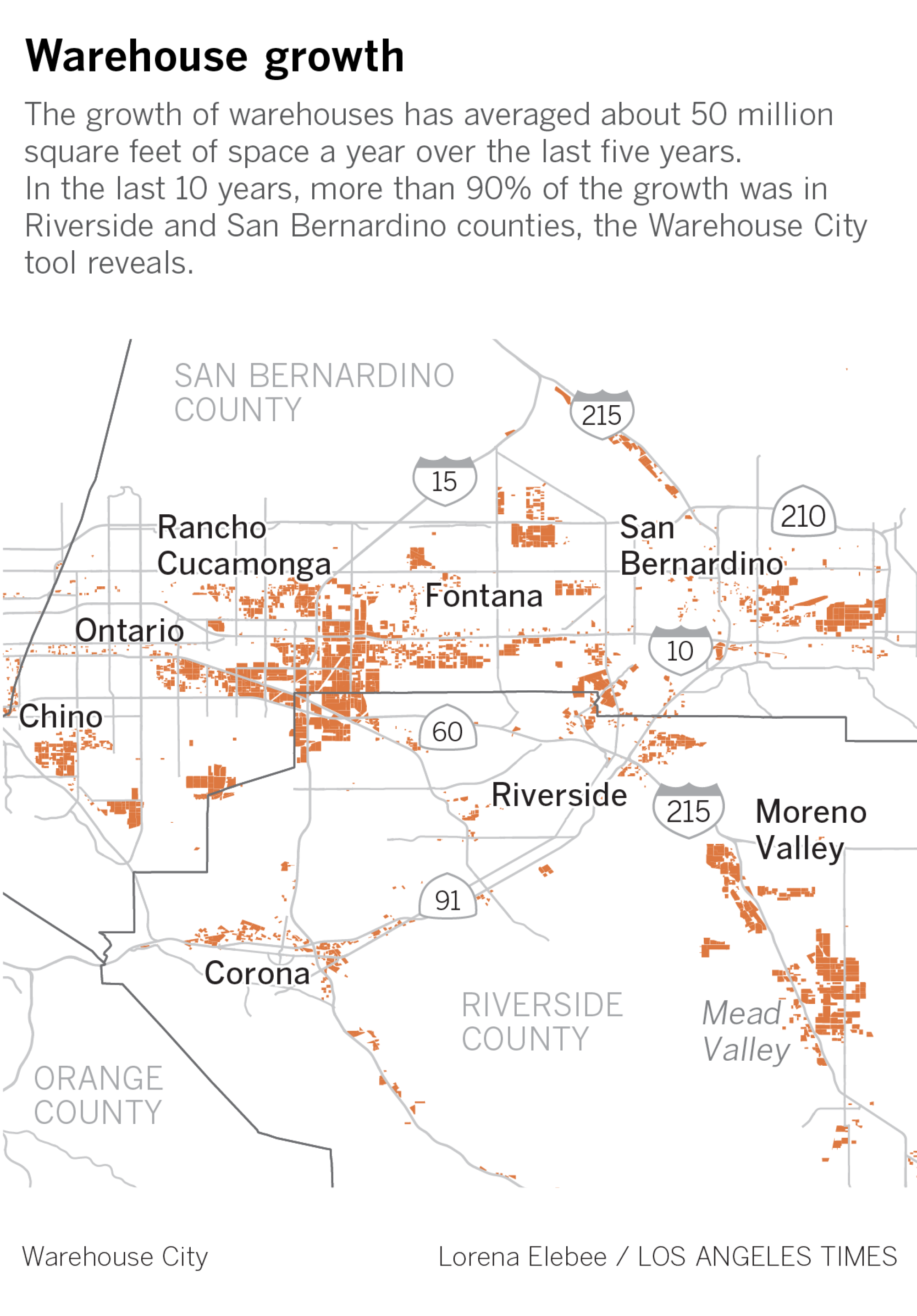

There are 170 million square feet of warehouses planned or under construction in the Inland Empire, according to a recent report by environmental groups. And despite fears of a recession, demand hasn’t ebbed.

But the rapid transformation of semirural areas into barrens of concrete tilt-up “logistic parks” is encountering a backlash. Residents are questioning whether they want the region’s economy, health, traffic and general ambiance tied to a heavily polluting, low-wage industry that might one day pick up and leave as global trade routes shift.

Several Inland Empire cities, including Colton and Norco, have placed building moratoriums on warehouses, as has Pomona, which borders the region. Environmental groups are pushing Gov. Gavin Newsom to declare a state of emergency, hoping to keep new warehouses away from homes and schools, where heavy truck traffic can expose children to high levels of toxic diesel emissions that have been linked to respiratory illness.

“Warehouse-induced pollution has created a state of environmental injustice and a public health crisis in San Bernardino and Riverside counties,” dozens of labor, environmental and community groups said in a letter last month urging Newsom to implement a regionwide moratorium on warehouses.

The group accused local politicians of environmental racism, ignoring health impacts while collecting donations from developers and their allies.

A spokesperson for Newsom said in an email to The Times that “California is taking urgent action to clean the air in communities hardest hit by pollution,” pointing to the governor’s order requiring heavy-duty truck manufacturers to transition to zero-emission vehicles by 2045. She did not say whether the governor supports a moratorium.

Local officials like San Bernardino County Supervisor Curt Hagman argue that a halt to building could have grave consequences.

“Lately, critics have called for warehouse moratoriums or outright bans. Their misguided proposals gloss over the real-world and draconian impact their potential bans would have on supply chains in local communities and the entire region,” he wrote in an opinion piece in the San Bernardino news outlet the Sun. “If we fail to keep pace with the growing demand for additional warehouse space, the result will be immediate and far-reaching throughout the Inland Empire — loss of good-paying jobs, less affordable housing, fewer environmental benefits and community infrastructure improvements, not to mention the gains other jurisdictions will make at our expense.”

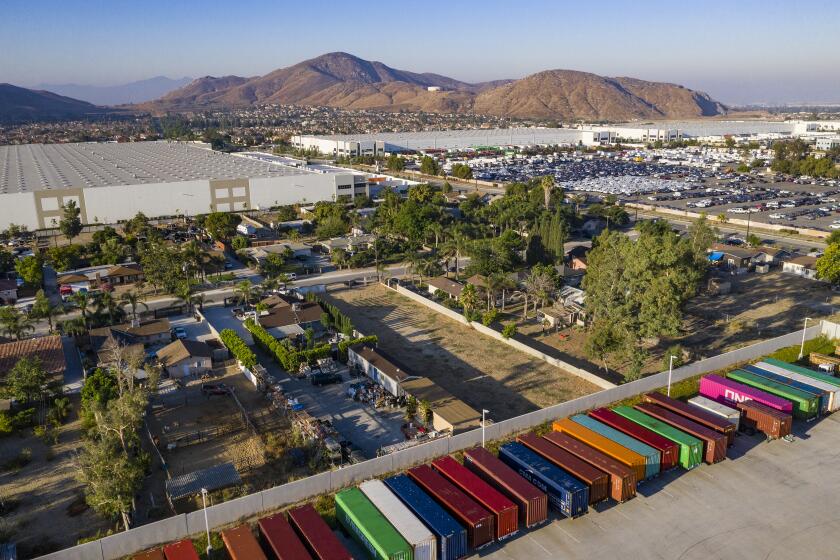

On a corner of the Bosch farms, cows lie in the shade of eucalyptus trees. The area was once largely an agricultural zone that has given way over the last decade to home tracts and warehouses. Heavy trucks have cracked the asphalt streets.

“We don’t even take the street anymore,” said Bosch, pointing to a road that leads to his family’s ranch home, where his son and grandchildren now live. He said it’s too dangerous.

“The trucks, they don’t watch out. They think it’s a dead street.”

In Ontario, there are an estimated 95,000 daily truck trips — nearly two for every household.

At one point, Bosch sought to expand his dairy farm, but the warehouse economy has become so pervasive that it priced him out.

“I asked one guy if I could rent his dairy, and he said, ‘Nah, why put up with the hassle of you renting?’” Bosch recalled, adding that owners earn more selling parking space. “The income from truck parking is lucrative.”

The logistics industry has moved into a void left as higher-wage jobs in manufacturing, defense and aerospace disappeared, converting largely agricultural and vacant land into the hub of America’s retail economy. The industry added more jobs in the Inland Empire than in any other part of the state. In 2022, it created 24,400 jobs in the area; in 2021, it created 27,400, according to John Husing, an economic consultant who specializes in logistics in the Inland Empire. Median wage ranges from $18.57 an hour for warehouse workers to $24.93 for drivers, he said.

“This is a job generator like mad,” he said. “Amazon has more than a dozen facilities out here. When the pandemic hit and people could not buy services, they converted to buying stuff, and a lot of that was done online. That really increased employment in the logistics out here, and it has held ever since.”

During the height of the pandemic, ecommerce made up 16% of U.S. retail sales, according to government data. Employment in the logistics industry was 51% higher at the end of last year than in February 2020, according to Southern California Assn. of Governments.

Truck drivers delivered every type of consumer good imaginable from the seaports and airports, as workers in the warehouses unloaded, sorted and reloaded them onto intermodal containers to be hauled by train and long-haul tractor-trailers across the deserts.

UPS and FedEx have Southern California regional operations in Ontario International Airport, Husing noted, which has become one of the nation’s fastest-growing cargo hubs. Amazon is the region’s largest private employer.

But other economists say many of those jobs don’t pay close to a living wage. The median hourly pay in the region is almost $5 below the California average, and turnover is high because of the grueling, nonstop work.

“Even with this impressive growth in the Inland Empire, logistics-sector jobs are generally lower-paying jobs, and they’re at very high risk of automation,” said Gigi Moreno, an economist at the Southern California Assn. of Governments. “You have automation and artificial intelligence in the logistics sector displacing workers, which means that the industry may not be able to support as many jobs as we do today. And this is even before considering any of the moratoriums on building warehousing. This is just the nature of what’s going on in the sector.”

The changes have strained communities. Many warehouses are built in low-income areas, where residents must put up with the traffic and pollution.

Fontana residents deal with noise and pollution while warehouses have been built and the Inland Empire has been transformed into a national logistics hub.

When the San Bernardino County Board of Supervisors met to vote on a project to rezone a semirural neighborhood in Bloomington for a massive warehouse complex, dozens of residents, activists and union construction workers came to speak passionately for and against it.

The board unanimously approved it, allowing the developer, Howard Industrial Partners, to build a warehouse and distribution space the size of 56 football fields. To make room, the school district agreed to relocate Zimmerman Elementary.

Environmental justice and conservation groups sued the county for neglecting to properly analyze the potential environmental damage. When operational, their lawyers argue, the complex would add thousands of diesel truck trips daily — on top of the truck traffic already choking the area. The lawsuit is pending, but families have agreed to sell their homes to make way for the new buildings.

“Development is creating an employment base and is an economic driver,” said Tim Howard, a founding partner of Howard Industrial Partners. He said warehouse projects have “transformed cities” like Fontana, providing employment opportunities and raising the quality of life.

But smog in the Inland Empire — largely caused by big-rig exhaust — is the worst in the nation, according to the the American Lung Assn.

Last year, California Assembly Majority Leader Eloise Gómez Reyes (D-Grand Terrace) introduced legislation that would have required a 1,000-foot buffer zone between new warehouses and homes, schools, day-care centers, playgrounds and other areas where people gather.

“If you’re concerned about the health of the community, you’re not going to build a warehouse with diesel trucks coming in and out, spewing diesel particulate matter right next to the schools or right next to the homes,” she said.

The bill also tacked on labor requirements for new structures.

But it faced opposition from a wide array of business groups and local municipalities. Hagman, then the chair of the San Bernardino County Board of Supervisors, opposed the legislation, writing to state Senate committee members that it “erodes local land use authority” and could put the county at a competitive disadvantage.

Reyes pulled the proposal after a state Senate committee sought to replace the setback provision with a one-year ban on warehouse construction, a move she felt went too far and would cause further polarization.

“I’ve never been anti-warehouse,” she said. “If in each of our cities and in each of our counties, if they did the planning of the communities in a responsible way, we wouldn’t be dealing with this, right?

“You could still have the warehouses,” she added, “but they would be planned in places where they’re not next to the homes. They’re not next to the schools. They’re not next to the day-care centers.”

Critics say that for too long, local governments have been part of the problem, rubber-stamping the projects and ignoring state environmental laws and the progressive damage that warehouses have caused communities.

There is “a very weak and minimal analysis” of the environmental damage distribution centers have wrought, said Susan Phillips, director of the Robert Redford Conservancy for Southern California Sustainability. Working with Radical Research, a consulting group specializing in atmospheric pollution, the conservancy released a mapping tool, “Warehouse City,” that shows the breadth of industry in the region overlaid with estimated truck trips generated and public data on pollution.

The environmental impact reports that are required by the state, she said, “are supposed to account for cumulative impacts, but they’re rarely adequate.”

The tool shows that the region has roughly 4,000 warehouses covering more than 1.5 billion square feet, including parking lots. More than 300 warehouses are 1,000 feet or less from 139 schools.

“The number of warehouses and the square footage of warehouses is mind-boggling,” she said.

Thirty years ago, there were 1,600 warehouses in the region, creating 140,000 truck trips daily, said Mike McCarthy, who runs Radical Research. The mapping found that the industry now generates more than half a million daily truck trips — nearly four times the diesel traffic as the population has almost doubled. The researchers also found that the average warehouse 30 years ago was about half the size of those built today, which average 500,000 square feet.

“They are running out of space; they are starting to go into the high desert, Imperial Valley and even the Central Valley,” Phillips said. “But they’re not stopping putting warehouses next to homes and schools in the Inland Empire. The amount of space they are using is leaving little space for anything else.”

The diesel trucks that serve warehouses spew out a cocktail of pollutants, including particulates that lodge in human lungs. Studies have linked the pollution to asthma, decreased lung function in children and cancer.

Southern California air quality officials are set to vote on rules that seek to cut pollution from trucks at 3,000 warehouses.

“We know diesel exhaust is a killer,” said William Barrett, national senior director of clean air advocacy for the American Lung Assn. “It’s one of the most damaging things that your lungs can experience.”

The rise in pollution and fears over climate change have pushed California air regulators to seek to ban the sale of diesel big rigs by 2040. In Southern California, regulators are attempting to limit emissions from warehouses.

Atty. Gen. Rob Bonta said he has been monitoring warehouse development across California for compliance with environmental rules.

“For too long, warehouses have proliferated throughout California with little consideration for the health and safety impacts on the surrounding communities,” he said in an emailed statement. “As a result of these poor land use decisions, many low-income communities and communities of color continue to be among the most pollution burdened in the state.”

Around the Bosch property in Ontario, much of what was once a capital of America’s dairy farms is now the nation’s capital of warehouses. There are more than 600 in the city, which has a population of 178,000. Dusty pastures disappeared as farmers fled to Texas, South Dakota and other states, and stately ranch homes became makeshift repair shops for big rigs.

“With COVID-19 and Amazon being like a superpower, you know, the warehouse craze just went crazy around here,” Bosch said. “I guess it’s progress, you know. I don’t like it so much.”

The market is so hot for warehouses that they are leased before they are even built, said Eloy Covarrubias, an investment broker at CBRE, specializing in industrial property. He estimates that there are between 38 million and 39 million square feet under construction — and more than half is already leased.

“There has been a significant amount of pent-up demand for that space,” he said, noting that the vacancy rate is about 1%.

That has cost the Inland Empire its agricultural roots, said Amparo Muñoz, former policy director at the Center for Community Action and Environmental Justice, a Jurupa Valley group that has been fighting warehouse development and signed the letter to Newsom.

Muñoz didn’t start off as an environmentalist. A trained engineer, she spent some of her time in warehouses checking and maintaining equipment.

“I really believed that if you let businesses regulate themselves, they do the right thing,” she said.

Her ideas changed after she had her second child. She had moved to Fontana a few years before, to a tract of homes surrounded by fields. She loved the pastoral life, the agricultural clubs and bunny farms. But by the time she was pregnant in 2013, an Amazon warehouse had been built less than two blocks from her home.

“At first you are like, hey, it’s not too bad,” she said.

She walked daily along the perimeter of her neighborhood to stay fit while pregnant, but what she thought were allergies worsened until she couldn’t breathe.

“The doctor asked me how long I had had asthma, and I was like ‘What? I don’t have asthma.’”

She learned that she had developed the condition in her 30s. Her son was born with asthma and had to have a breathing mechanism for the first year of his life.

“They told me it was environmental factors,” she said. “I didn’t think about all the trucks that were idling at the warehouse when I was walking by them.”

The family spent around $22,000 to install high-grade air filters and a new duct system in their home.

“A lot of time, kids wake up with bloody noses on their pillows,” she said. “We have the worst air quality. We have gridlock. We have streets and communities that were never built for global logistics. We’re basically building, on top of failed infrastructure, a global network.”