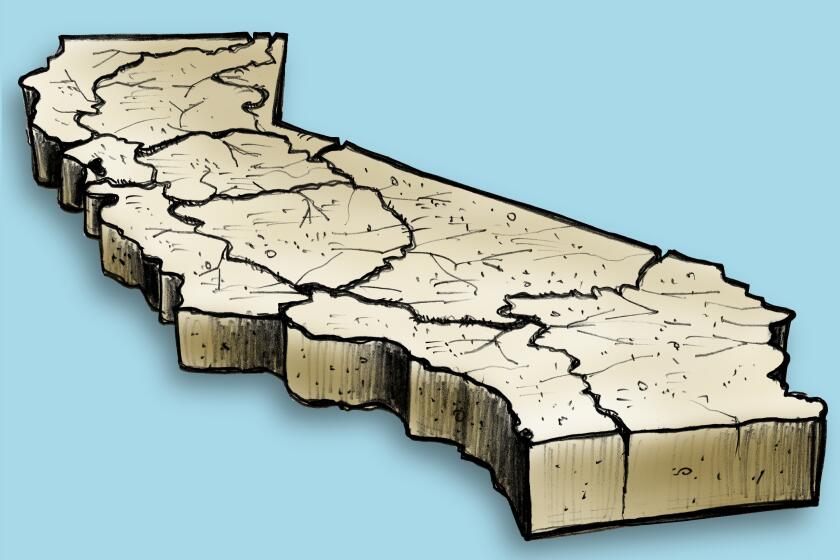

California set for more brown lawns and water restrictions as state issues 5% allocation

Californians should brace for another year of brown lawns, tight water restrictions and increased calls for conservation as state water managers Thursday warned that severely reduced allocations are once again likely in 2023.

The Department of Water Resources announced an initial allocation of just 5% of requested supplies from the State Water Project — a complex system of reservoirs, canals and dams that acts as a major component of California’s water system, feeding 29 agencies that together provide water for about 27 million residents.

Water managers will monitor how the wet season develops and reassess the allocation each month through spring, officials said. But California typically receives the bulk of its moisture — both rain and snow — during the winter, and current forecasts are leaning toward a fourth consecutive year of dryness despite the recent storms.

“California and most of the western U.S. states do remain in extreme drought conditions driven by climate change, and as water managers, we are adjusting to these hotter and drier conditions,” said Molly White, operations manager for the State Water Project. “We are taking a very cautious approach with respect to planning for next year, should next year be a fourth drought year in a row.”

More dryness, extreme weather events and water quality hazards are likely in 2023, state water officials said Wednesday.

Indeed, climate change-driven heat and dryness are quickly sapping the state’s supplies. Lake Oroville, the largest reservoir on the State Water Project, is at just 55% of its average capacity for this time of year, White said.

Officials said they will continue to assess requests from water suppliers for critical health and safety needs, such as water for fire suppression and sanitation purposes. They are also working with senior water rights holders on the Feather River downstream of Lake Oroville to monitor conditions and assess water supply availability should dry conditions persist.

Mike Anderson, state climatologist with the DWR, noted that California is rounding out its driest three-year stretch on record.

“We’re finding new extremes in each drought, and then finding that it can be even more extreme as the world continues to warm,” he said.

The latest maps and charts on the California drought, including water usage, conservation and reservoir levels.

Though the initial 5% allocation is tight, it marks a minor improvement over last December, when it was at its lowest ever, zero percent. The final allocation for 2022 ended up being 5%.

Should 2023 again end up at 5%, it would mark the third consecutive year at that amount, according to state data.

For many residents, that means a critical supply “could remain at a trickle,” said Adel Hagekhalil, general manager of the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, the region’s massive wholesaler.

“After the three driest years in state history, we are certainly hoping for some reprieve this winter. But the tough reality is, we must be prepared for this historic drought to continue,” Hagekhalil said in a statement. “This initial allocation is an important indicator of what Southern California should be ready for in the months ahead: very limited supplies from the State Water Project.”

But state supplies are only one piece of California’s water pie, and conditions are similarly concerning at the federal level, where drought has sapped the Colorado River so severely that it’s its reservoirs are at risk of reaching “dead pool” status, or the point at which water drops below a dam’s lowest intake valve. The river has long been a lifeline for the West, but officials there have also warned the region to prepare for painful cuts as they push for scaled-back use.

Hagekhalil said such warnings, along with the low state water allocation, mean everyone in Southern California should reduce their use of imported supplies. State water-dependent areas have already been under one- or two-day-a-week outdoor watering restrictions for months, but the MWD may soon expand those rules across their entire service area.

“Our initial call for increased conservation regionwide will be voluntary, but if we don’t see significant precipitation this winter, Metropolitan may implement a water supply allocation plan for its entire service area, requiring mandatory restrictions across the region,” he said.

Colorado River reservoirs are dropping amid drought and climate change. The Biden administration has announced new measures to address the crisis.

Officials at the state level said they are considering other actions to help stretch supplies, including a temporary urgency change petition and reinstallation of an emergency drought salinity barrier in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta. The move would allow the State Water Resources Control Board to modify certain outflow and salinity requirements in the delta, giving water managers the ability to conserve more supplies upstream, White said.

Some experts were critical of the strategy, especially from an environmental perspective.

“The temporary urgency change petitions have been used as a way to allow the state to violate the minimum water quality standards to protect fish and wildlife in the delta,” said Doug Obegi, a senior attorney at the Natural Resources Defense Council. “They clearly harm delta smelt and salmon and other species, and they don’t actually improve conditions upstream for fish and wildlife.”

Obegi said he hoped instead to see the state reduce its reliance on the delta and invest more in local and regional supplies, including through projects such as the MWD’s Pure Water Southern California, which aims to significantly improve water recycling in the region.

“It is those kinds of investments that will help make Southern California more drought-resilient and create a lot of good-paying jobs in the process,” he said. “Unfortunately, those are not short-term solutions, and the fact that we haven’t made those kinds of investments and are really far behind the state’s recycling goals for the last several decades is part of the reason why we’re still in the mess we’re in.”

Recurring drought and rising temperatures have already begun to alter the landscape of California and the American Southwest, researchers warn.

But state officials on Thursday also underscored that adaptation and conservation will be critical as climate change continues to alter the landscape of California.

“We are in the dawn of a new era of State Water Project management as a changing climate disrupts the timing of California’s hydrology, and hotter and drier conditions absorb more water into the atmosphere and ground,” DWR director Karla Nemeth said in a statement. “We all need to adapt and redouble our efforts to conserve this precious resource.”

Should storage levels improve as the wet season progresses, the DWR will consider increasing the allocation, Nemeth said. The state is also working to employ new technologies such as aerial snow surveys to help improve its forecasts.

“This early in California’s traditional wet season, water allocations are typically low due to uncertainty in hydrologic forecasting,” Nemeth said. “But the degree to which hotter and drier conditions are reducing runoff into rivers, streams and reservoirs means we have to be prepared for all possible outcomes.”

The final allocation will be determined in May or June, officials said.