Column: Mike Davis’ final email to me captured the L.A. ‘sewer explosion’ — and reminded me to write, not mourn

- Share via

After leaked audio of Los Angeles City Council members saying all sorts of bigoted blabber unleashed a political earthquake, I got an email from a much-missed voice.

“Even if the tape was made a year ago,” Mike Davis wrote to friends, family and me on Oct. 13, “its release correlates to the unexpectedly strong performance of progressive candidates in the June primaries and should be interpreted in that light.”

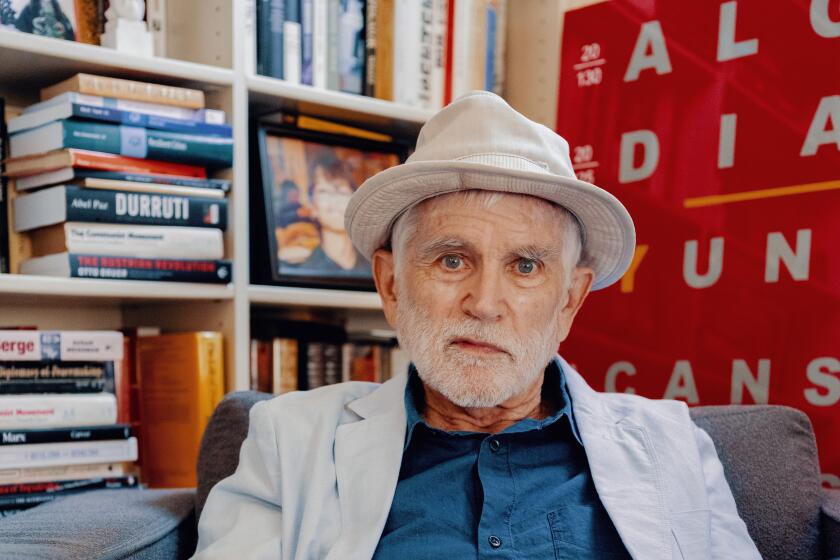

We had last talked in July, when the two of us spent hours at his San Diego home chatting about his life and, well, life. Mike had decided to end chemotherapy. The author of so many books that predicted the Los Angeles of today at its best and worst — “City of Quartz,” “Ecology of Fear,” “Magical Urbanism” — wanted to spend his last days with his wife and children and read, not write.

So his surprise note about what he deemed “the sewer explosion at 200 N. Spring” (referring to L.A. City Hall’s address) was a joy. Though brief, it was classic Mike: Unsparing. Brilliant. Funny. Caring. Prophetic.

Davis blasted the four paragons of Latino political power on the tape — then-Los Angeles Labor Federation president Ron Herrera, then-L.A. council President Nury Martinez, and Councilmembers Gil Cedillo and Kevin de León — for trying to dilute Black political power in the city.

He described Martinez — who called the Black son of Councilmember Mike Bonin a “negrito” and compared the boy to a “monkey,” derided L.A. County Dist. Atty. George Gascón for siding “with the Blacks,” and also trashed Jews and Armenians — as the “Exalted Cyclops” of her cabal.

He praised an ascendant Left in L.A. for posing “a threat not just to mainstream Democratic personalities but more generally to the ethno-dynastic structure of local politics.” And he ended by turning Martinez’s slurs against Oaxacans, whom she had dismissed as short, dark and “ugly,” into a pledge for solidarity with a hearty “Nosotros somos oaxaqueños!” — we are Oaxacans — while jokingly referencing his own diminutive stature.

I congratulated him on his usual prescience and vowed to visit again after the election.

I never had the chance.

A mutual friend texted me the news that Davis died Tuesday at age 76 from complications of esophageal cancer. I felt sad for about a minute, then remembered the famous slogan associated with the late labor leader Joe Hill: Don’t mourn, organize!

It’s all Mike ever wanted his readers to do, even in the face of doom. Especially in its face.

With ‘City of Quartz’ and other influential works, Mike Davis shaped generations of thinking about Los Angeles and its origins.

The Los Angeles of today is the one Mike long warned about, except even more dystopian. The white power structure he inveighed against again and again has become more diverse but no less self-preserving. Law enforcement continues to antagonize communities of color even as the rank-and-file nowadays are majority Latino. The environment, an issue that especially saddened him, continues its precipitous, manmade decline. To paraphrase Mike’s most infamous essay, it’s not just Malibu burning every fall — it’s the entire damn state, all the time.

This chaos is what the most superficial Davis readers, the ones who kept calling him a prophet of doom despite his protestations, will say that he nailed. They’re not paying attention to the inspiration to fight that his true readers found in his warnings.

He’s the only intellectual I know with fans in academia, at factories, on the streets and in politics, all fighting Davis’ good fight of people power. Mike spoke at their classes, showed up to their rallies, responded to their emails, promoted their causes, invited them to his home and never asked for anything in return. Though Davis left Los Angeles for San Diego over 20 years ago, dismissed then by naysayers and boosters who mocked his civic jeremiads as alarmist nonsense, his modern-day vindication gave solace to activists that they, too, could one day win.

Mike was more than a muse to them. He was one of them.

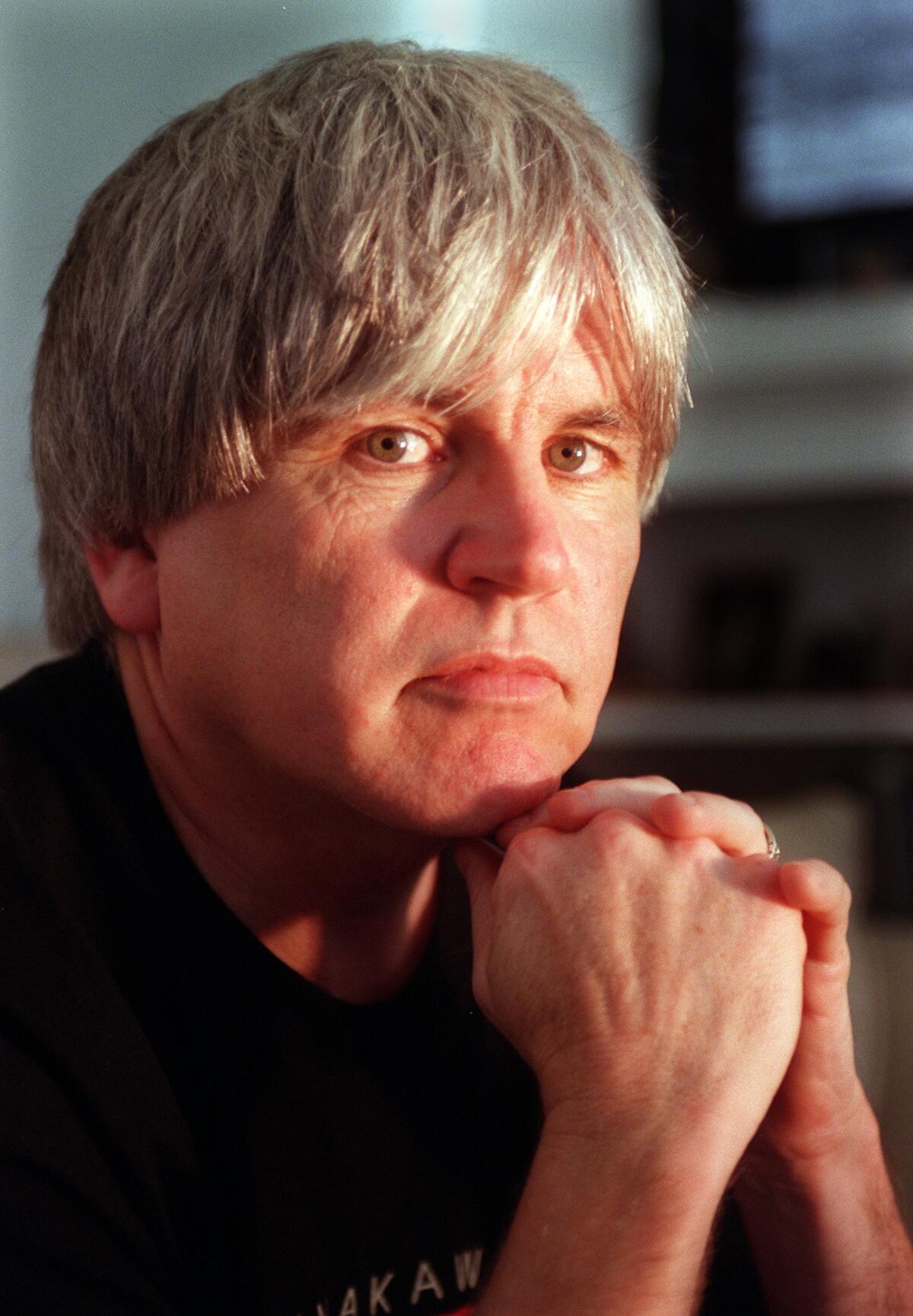

I think that’s what prompted Mike to send that email to me and others in his circle. The widespread disgust over the racist L.A. council tapes is a cross-cultural, classless movement the city hasn’t seen in decades but which Davis celebrated in his last book, 2020’s “Set the Night on Fire: L.A. in the Sixties,” along with co-author and longtime friend Jon Wiener. That he was paying attention to what was going in his last weeks speaks to his convictions — and joys.

He’ll go down as the most influential California chronicler since Charles Fletcher Lummis, who was the 19th century sunshine to Davis’ 20th century noir, to borrow one of Mike’s most famous lines.

Many will compare Davis’ skeptical eye to that of Joan Didion — but she never offered a solution to our problems, and her fans were almost exclusively literati, not the folks shaping the Los Angeles of today and imagining a better tomorrow.

A better comparison is Carey McWilliams, whose 1946 book “Southern California: An Island on the Land” remains the best sociocultural analysis of the region ever written. Praised by Davis as a “one-man think tank,” he was every bit the crusading writer Davis was, tackling racism and labor exploitation in an era — the Great Depression through the beginnings of McCarthyism — when it was harder to do so.

But McWilliams left California in the early 1950s to become editor of the Nation — too soon to have created as large and sprawling a school of disciples as Davis. Only the most committed history nerds remember his legacy. Davis touched too many walks of life to ever fade away.

I want to say we’ll sorely miss Davis at a time he’s needed more than ever, but it’s not true. Every time there’s a protest against hate and corruption, every time workers strike for better pay and working conditions, every time people push for a fairer California, every time someone unearths long-hidden histories or dismantles long-held narratives, he’ll be there — a modern-day Tom Joad.

Shortly after news of his passing, I replayed the tape of my talk with Mike from the summer. I marveled anew at his wit, his heart, his memory and his insights.

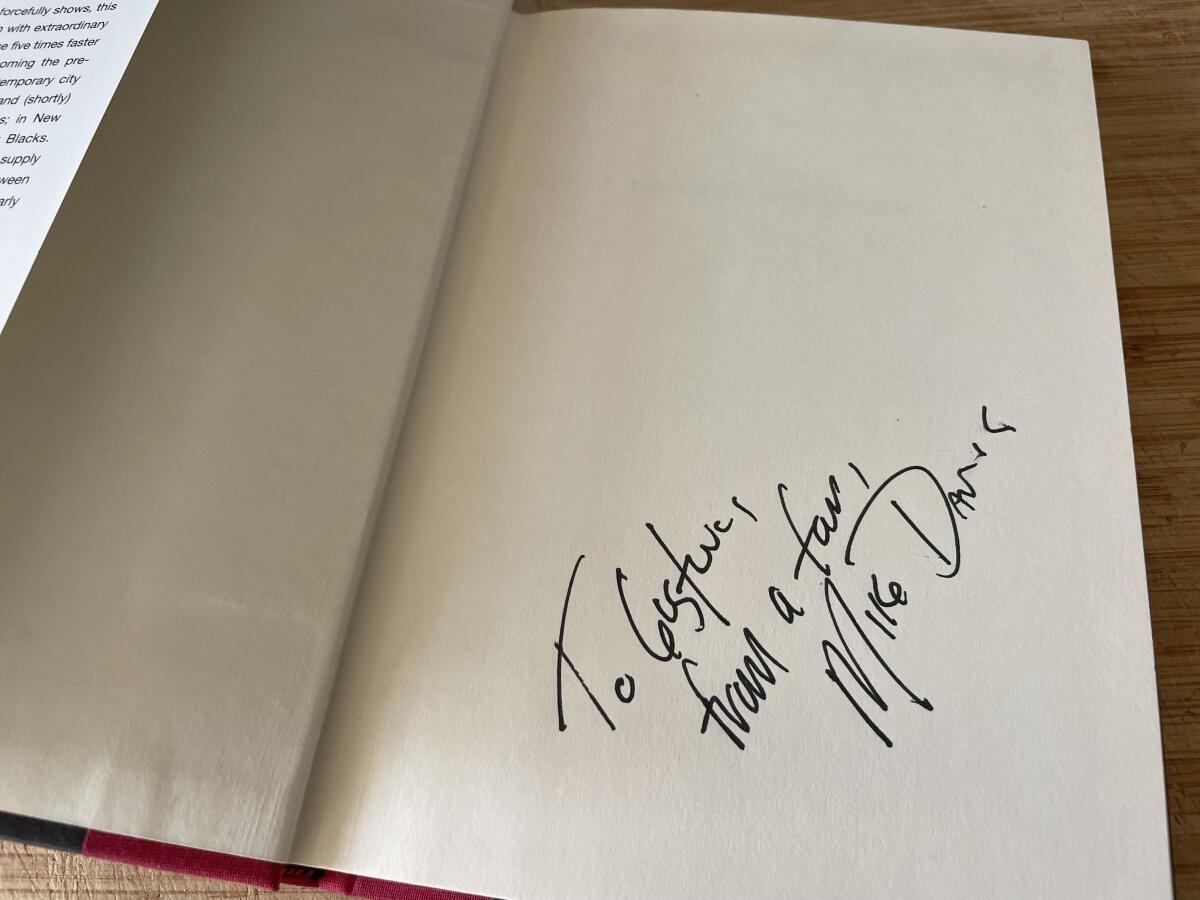

What I rewound to play again and again was the very beginning, when I tried to thank him for inscribing one of his books as “From a fan” nearly 20 years ago, a time where I didn’t even have a full-time job as a reporter. He wouldn’t hear it.

“I want to, first of all, thank you for going after the sheriff,” Davis said, referring to Los Angeles County Sheriff Alex Villanueva. “This has been the most wonderful stuff the Times has done in years.”

He could’ve basked in my adulation but instead praised me. And he wasn’t done.

“Although you must be a little apprehensive at times if you see somebody outside your door,” he added.

We both laughed, then just hung out for the rest of the afternoon.

Mike, I’m not mourning your passing. I’m writing.