This YouTube star wants to be governor. He’s the best-known Democrat on the recall ballot

The scene hinted at modern-day political fable: “Mr. Smith Goes to Washington,” launched by a rocket of YouTube fame.

A young, ambitious candidate in a suit jacket and jeans stood on a stump in Echo Park, surrounded by 50 people cheering and filming on their iPhones as he laid out his vision for California.

Radiating the magnetic appeal that boosted his YouTube channel to 1.7 million followers, Kevin Paffrath dispensed with his usual financial advice to pitch himself as an unlikely recall candidate that voters can take for a gubernatorial test drive.

“Shouldn’t all politicians have a one-year trial?” he asked. “Kick them out when they suck, right?”

Paffrath spends several hours a day recording videos from his Ventura County home, drives a Tesla plastered with a giant picture of his face and has never held elected office. And, through various quirks of an unlikely recall season, there is a chance this 29-year-old running on a “Stop the bullship” slogan could be California’s next governor.

Is it likely? No. But it’s far from a statistical impossibility.

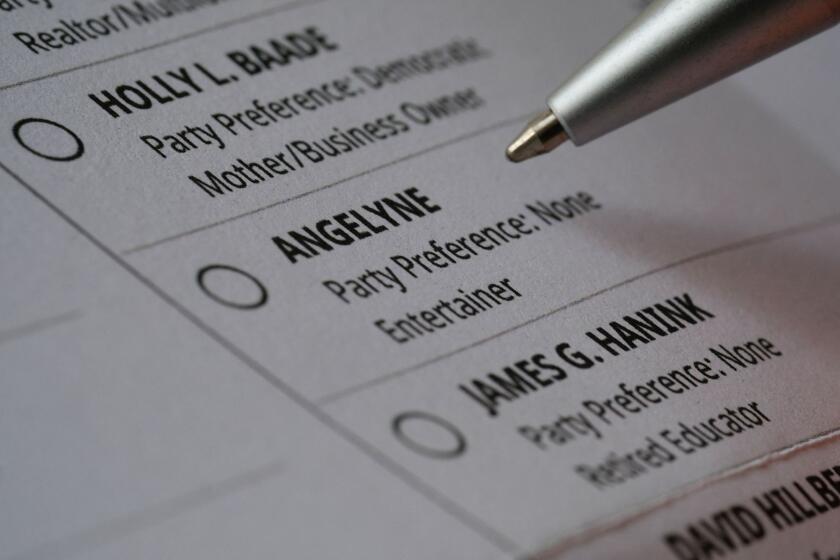

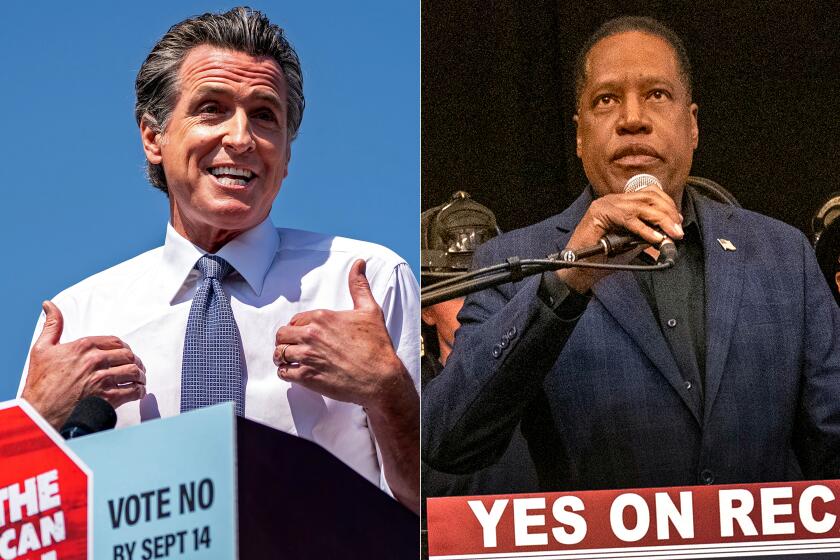

With no prominent Democrats running to replace Gov. Gavin Newsom, Paffrath has become the de facto choice for a quotient of party faithful who oppose the recall but still want to mark their ballots with a Democratic backup candidate.

What you need to know about California’s Sept. 14 recall election targeting Gov. Gavin Newsom.

Political strategists say Democrats who plan to vote on the recall ballot’s second question are largely deciding between Paffrath and former San Diego Mayor Kevin Faulconer. The moderate Republican took a swing at Paffrath in the most recent debate, saying, “It’s not the time for the on-the-job-training for YouTube.”

But for some voters, Paffrath is a pragmatic option who they think will at least protect Democratic interests. They cite his pledge to appoint a Democratic senator if 88-year-old Sen. Dianne Feinstein were to step down before the completion of her term.

“I don’t think he’s a good choice. I just think he’s a slightly better choice than [Larry] Elder or a blank answer,” said Elaine Loh, an L.A. writer who voted for Paffrath.

In a race packed with longshot entrants, Paffrath’s unlikely candidacy was propelled to the mainstream — or at least the fringes of the mainstream — in early August, when results from a SurveyUSA poll pegged him as the leading replacement candidate, with 27% support. (California political analysts have often questioned SurveyUSA’s methodology, but that didn’t slow the crop of headlines about Paffrath leading the field.)

The poll “was kind of a surprise to all of us,” said Gabriel Gottfried, a 20-year-old Meet Kevin fan-turned-staffer who took a leave from college to move into one of Paffrath’s properties and work for the campaign. “It really changed the whole way the campaign functioned. The media’s attention on us grew tremendously.”

More recent polls have shown their campaign trailing Elder, with Paffrath’s share of the vote ranging from 6% to 22%.

Gottfried is one of four full-time campaign employees who operate out of a garage-turned-war room in the home in Ventura that Paffrath shares with his wife and two young sons. Born in Germany and raised in Florida, Paffrath met his now-wife Lauren on a high school trip to Europe and eventually moved in with her family to finish high school in California.

He started learning the real estate business from his future father-in-law as a teen and found moderate success in his early-to-mid 20s, selling houses in Ventura County as “Meet Kevin, The No-Pressure Agent” and investing in fixer-upper rental properties. But the real success — and money — came later, when Paffrath took his Meet Kevin brand to YouTube, where he built a following sharing his wealth-building philosophy. He earned more than $3 million in YouTube ad revenue over the last year, according to screenshots from an internal YouTube dashboard that Paffrath showed to The Times.

He did manage to fit at least one political job on his resume. In high school, Paffrath interned in the Ventura city manager’s office, where he impressed then-City Manager Rick Cole. The 17-year-old Paffrath showed up at Ventura City Hall every day in a suit and tie and was “focused on doing good in a very earnest, very straightforward way,” Cole said.

Cole insists the political naïf is heartfelt in his public service ambitions. Still, Cole was surprised when Paffrath texted him in early May to say he was running for governor. (Paffrath has, by his own account, been in politics for a little over four months. He privately decided to run “a few days” before announcing it on YouTube, he said.)

“Kevin, I love you, and I know you’re sincere, including about solving homeless, but the recall election is a joke,” Cole texted back. Paffrath quickly countered with an invitation for Cole to join him for a live YouTube conversation.

Cole still opposes the recall, but said he voted for Paffrath on the ballot’s second question.

Many California Democrats are flailing for answers about how to approach the ballot’s second question: If the governor is recalled, who do you want to replace him?

Paffrath has offered plenty of audacious and occasionally far-fetched plans for California — the list includes legalizing gambling, creating a network of free, trade school-like “future schools,” building a water pipeline from the Mississippi River and ending homelessness within 60 days of taking office.

Paffrath’s pro-recall stance has led some to question his party bona fides, though the candidate has been registered with the party for more than a decade.

During a recent televised debate, Paffrath urged the Republican opponents sharing the stage with him to drop out and endorse his candidacy. But, broadly speaking, he still agreed with them more than he disagreed, particularly on issues like lowering taxes and streamlining approvals for building new housing.

In recent weeks, Paffrath and his team have been criss-crossing the state by rented private plane, holding small rallies, meeting voters and occasionally crashing Newsom’s own events.

“I just stand there though — don’t want to be ‘that’ YouTuber kid,” Paffrath said via text message of the Newsom events, acutely aware that the platform that brought him fame has a complicated role in American discourse.

Anyone making a living off their personal brand is, to some degree, a hustler; the same could be said of anyone running a political campaign. But the two arenas have historically been governed by slightly different mores.

Paffrath self-identified as a YouTuber in his campaign announcement press release, but also often complains that he is being written off as a social media prankster rather than a serious candidate.

Though his early YouTube oeuvre included a heavy quotient of trolling (he was charged with trespassing after showing up at entrepreneur Grant Cardone’s Florida office dressed as an elf in 2018, though the charges were later dropped), Paffrath maintains that he left all that behind in 2019 and has walked a markedly more serious path over the last 2½ years.

Paffrath laughed heartily when a Times reporter responded by reading a selection of sensational-sounding titles from the “Governor Videos” section of his Meet Kevin app, which include “i just got banned,” “I JUST exposed California on Live TV,” “Crypto JUST Flipped | Big Change!!” and “Fox News JUST confronted me LIVE on TV.”

“There’s no question that Kevin’s impact on this race derives directly from his media savvy. So in that sense, he’s more like Frank Capra than Mr. Smith,” Cole said, contrasting the protagonist of the 1939 film — an idealistic young Boy Scouts leader appointed to the Senate — with the creative force behind the box office hit.

Early numbers provide good news for Newsom but also show he must turn out young and Latino voters.

Many of Paffrath’s campaign videos include discount codes for online classes he teaches and links to referral codes for a range of items, including air purifiers, cameras, mattresses and Teslas, which Paffrath does not see as an issue.

“YouTube’s my platform. This is where I share my content and that’s how I make my living,” Paffrath said, clarifying that, if he were to be elected governor, he would have a separate governor channel without affiliate links for official business.

While Paffrath’s subscriber count has trended upward over the last year, he said campaign content tends to perform poorly, pushing back on the notion that his candidacy might be a tactic to grow his overall brand.

Paffrath, who says he has no paid political advisors, has sometimes drawn attention for his unconventional tactics, including the decision to put up multiple campaign billboards in Texas with the slogan “Send Californians back to California” — a reference to the so-called exodus of Californians to more business-friendly states like Texas, a trend that Paffrath says his governorship would reverse.

“We’d love to also get the attention of people like Elon Musk and Joe Rogan, so we kind of plopped them on the roads to their places,” Paffrath explained. (Musk and Rogan both announced moves to Texas last year.)

Paffrath’s Mississippi River pipeline proposal drew buzz when he pitched it during the debate, along with derision from water experts, who dismissed it as an implausible solution that would also be prohibitively expensive.

Speaking a week after the debate, Paffrath said he still liked the idea but also conceded that it might not be feasible.

The point, he said, was to ask the big questions that get people talking about big solutions.

“Look, I don’t have all the access to all the water departments and all the water professionals,” Paffrath said, adding that if he won, his team would do all the research necessary to make their plans a logistical reality.

“And if something is a bad idea, we’re not going to do it,” he said. “We’re not stupid.”