Conservative activists push voter fraud claims to recruit an army to police California recall polls

- Share via

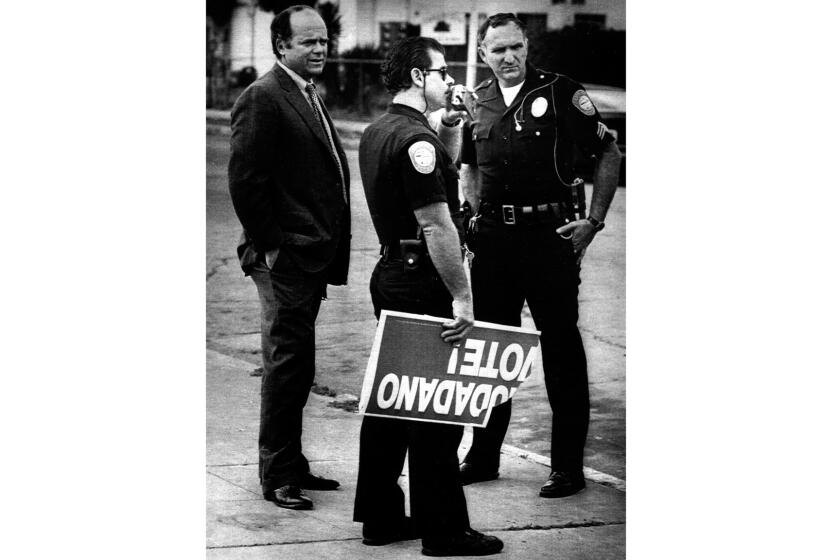

Conservative activists who have long promoted unproven and often false claims of voter fraud in California are spearheading a major new effort to capitalize on the upcoming gubernatorial recall vote, attempting to recruit tens of thousands of volunteers to police the polls on election day.

The effort is the outgrowth of a campaign waged for nearly three decades to challenge ballots and voter registrations in California — one often aimed at immigrants, a Times investigation has found.

In November, volunteers from one of the fraud watch groups, the Election Integrity Project, caused disruptions at the polls, sometimes intimidating voters, according to election logs, emails and records filed in federal court.

An observer in Nevada County raised concerns about the race of a woman seen removing ballots from a drop box outside the county building, according to county records. The woman, who was Black, was the county registrar’s wife.

In San Diego County, a volunteer poll watcher upset voters by telling them they should surrender their hand-delivered mail-in ballots so they could be canceled and instead vote in person. And in Orange County, an observer attempted to interrupt a couple voting together, and another caused a disturbance for three hours by trying to interview voters as they left. “Inspector wants her gone but is unsure of how,” the call log noted, under the heading “Voter Intimidation.”

The activists’ increasing focus on policing the polls extends beyond observing the process of voting — which is allowed by law — into the legally murky practice of challenging votes by questioning the authenticity of signatures on mailed ballots.

In a recent ruling, a judge in one county said observers are not legally allowed to challenge signatures on ballots, but elsewhere across the state, The Times found Election Integrity Project volunteers were often successful in pressuring election officials to give ballots a second level of review. The challenges at times became so frequent, observer reports filed in court show, that some registrars shut the observers down in order not to impede the election.

“They were interfering with voters. They were interfering with our process,” Neal Kelley, registrar of voters for Orange County, said of Election Integrity Project watchers. “They chew up resources like you wouldn’t believe. … Eighty percent of the time it was just nonsense.”

The activists are part of a national surge in poll policing, from Florida to Colorado. In California, the top cop is Linda Paine, a former Santa Clarita tea party activist who founded the Election Integrity Project and claims California — which has one of the country’s most permissive approaches to voting — is part of a national scheme to replace the “constitutional Republic” with a “globalist socialist oligarchy.”

In an email to The Times, Paine said her group has “trained thousands of volunteers and it is very uncommon for them to violate” its policies. Though reports filed by the organization’s observers make clear that they challenge ballot signatures, Paine said the Election Integrity Project does not train them to do so but instead instructs them to observe procedures and “ask questions of those in positions of authority.”

Paine and other election fraud activists portray California as an ominous warning for the rest of the nation, claiming without evidence that election rules adopted to boost voter turnout, particularly in poor and marginalized communities, allow noncitizens to vote and open the door to widespread fraud. Those rules include automatically offering to register people to vote when they obtain or renew a driver’s license, expanding vote-by-mail systems and allowing election day registration.

The Riverside County investigation illustrates the challenge authorities face when dealing with allegations of massive voter fraud.

Buoyed in recent years by support from Republican Party officials and major conservative donors, the Election Integrity Project and a second organization, the Institute for Fair Elections, have challenged more than 3 million voter registrations since 2018, The Times found.

Registrars each year update millions of records based on death indexes and postal databases but are wary of removing anyone for whom there is not conclusive information, choosing enfranchisement over purity. California also does not share voter records with other states, making it harder to identify people who are registered in multiple states.

Still, new California data submitted to the federal Election Assistance Commission show a sharp increase since 2018 in removals of outdated or bad registrations, doubling statewide and tripling in Los Angeles County.

Subscribers get early access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers first access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

The activists hunt through these changing, imperfect voter rolls to compile lists of registered voters they say should be removed because they are probably dead, have moved, have multiple registrations, haven’t voted in years or, in some cases, are guilty of double voting.

They have had uneven success in demanding that state and local election officials investigate the names on those lists. Interviews, state government records and data analyses by The Times show activists often made major errors or targeted problems that had already been corrected. Still, these continued claims have succeeded in promoting suspicion in conservative enclaves that fraud is a significant problem in California’s voting system.

Addresses they flagged for having suspiciously large numbers of registered voters included college dormitories, convents and a monastery. Lists of voters whom activists claimed no longer lived at registered addresses and should have their voter registration canceled included members of the military away from home on active service.

Four dozen people accused of voting twice in the March 2020 primary — among 9.6 million ballots cast — turned out to include 32 cases in which election computers erroneously listed them as voting twice. Among the remaining suspects were a set of twins whose names differed by a single letter and elderly people who election officials said probably forgot having voted before doing so a second time.

In 2016, the Institute for Fair Elections alleged in testimony before a federal voting commission that one person, Jung Kim, illegally voted 14 times in five elections. The Times found the votes were cast by three different people who share the same first and last names but live in different apartments in the same large downtown Los Angeles complex. The three had different ages and were all registered under different political parties.

The institute did not respond to a request for comment on the misidentification.

One voter identified by The Times as registered in two different places at the same time: Anne Hyde Dunsmore, who heads the Institute for Fair Elections and is one of the main fundraisers for the recall.

Dunsmore, registered in both Florida and California as of May, said she had no way of removing her name from Florida’s rolls when she moved, though The Times found the form available on the website of the registrar’s office where she previously lived. Dunsmore did not respond further. She did not vote in both states during the same election, but it is that kind of registration lapse that her group and other activists argue puts California’s elections in peril.

With the state on the brink of a nationally watched recall election this fall, activists are promoting their claims to raise money and recruit volunteers as well as to propel conspiracies of stolen elections.

Paine this year announced that the Election Integrity Project aims to recruit 30,000 people for the recall election to monitor polling places and vote processing centers, where fraud-seeking observers challenged voter signatures. The call to action is circulating among Republican women’s groups, carried on social media platforms for the recall and promoted at private dinners, church gatherings, on internet election watch conferences and at other events, including a Huntington Beach rally in March that featured a gigantic Trump 2024 banner.

Prominent recall proponents as well as local Republican Party leaders urged supporters to join the effort, which is likely to also focus on next year’s midterm election, in which a handful of California races have national implications for the balance of power in Congress.

Paine, who declined to be interviewed for this story, has said the stakes are nothing less than democracy itself.

“Year after year, [California legislators] have passed laws that actually have destroyed the integrity of the election process and made it very easy for those who would be willing to manipulate the system to do exactly that,” Paine told a conservative Christian organization in January. “This is a coup on the United States.”

::

California’s election fraud campaigns intersect with the state’s immigration battles.

The campaign for Proposition 187, a 1994 ballot initiative to deny state services to immigrants in the country illegally, included unfounded claims that large numbers of undocumented immigrants were illegally voting in California elections. Immediately after the campaign, one of the initiative’s authors launched a crusade to hunt for fraud, and a legislative consultant joined the effort by creating a list of 170,000 suspect voter registrations. Her group became today’s Institute for Fair Elections.

Fifteen years later, Paine, who had recently founded the Santa Clarita chapter of the tea party and spoke out against amnesty for people in the country illegally, argued that California elections failed to represent those with conservative values. In 2010, she created a California offshoot of a controversial Texas-based tea party campaign, called True the Vote, to police the polls.

Paine registered the organization as a for-profit venture in Wyoming, where it is not required to disclose directors or finances. In 2017, she opened a nonpartisan tax-exempt charity in California — though the Wyoming corporation still exists and Paine herself moved to Arizona. In March, she formed a public benefit corporation in Wyoming that is permitted to advocate on behalf of candidates and ballot issues. It “has more flexibility in its activities, such as more extensive lobbying, and less disclosure of donors,” she wrote to supporters.

The myth of undocumented immigrants traveling from poll to poll to illegally vote goes back more than three decades in California and has spread nationwide.

The claim of mass voting by undocumented immigrants remains a motivating force. At a 2019 Placer County recruitment meeting with Paine, a local tea party leader said he was moved to join Paine’s group as a poll observer after hearing secondhand that a van carried migrant workers from poll to poll during a local assembly election at the behest of the United Farm Workers union.

“I can’t say I actually [saw] vans pull in loaded with undocumented illegals,” he said, according to a video of the event. “What I can tell you is this: In my heart, in my gut, I know I stopped many buses and many vans from coming in.”

California permits citizens to observe nearly every part of the voting process. Many organizations in the state train volunteers to help ensure that voters get access. But the Election Integrity Project’s volunteers are schooled in ensuring poll workers and voters follow the letter of the law, as they understand it.

The organization says it has trained 13,000 poll watchers over the last decade and received only five complaints from registrars.

Election officials in eight counties, however, were critical of the hundreds of observers the Election Integrity Project dispatched to their polls in November.

They told The Times most volunteers appeared well-meaning but distrustful, and focused on trivialities they often take to confirm their suspicions of fraud.

November election incident reports and interviews from six counties — Fresno, San Diego, Orange, Nevada, Sacramento and San Luis Obispo — describe Election Integrity Project observers protesting that they could not stand close enough to hear everything poll workers said to voters; complaining about couples voting together, even though they are legally allowed to; and calling out procedural deficiencies, such as the orientation of voting booths or presence of water bottles.

Paine apologized by email to the registrar of Nevada County after one of her group’s observers raised concerns about the registrar’s wife, who is Black, removing ballots from a drop box outside the county building. Paine said the volunteer would be dismissed, according to emails reviewed by The Times.

“She was gushing with apologies. ‘That’s not what we’re here for,’” the county’s registrar, Gregory Diaz, told The Times, “but in my eyes, that’s exactly what they’re here for.”

In her email to The Times, Paine said that the observer’s actions violated her organization’s policies and training, and that the observer was dismissed. In the rare instances in which a volunteer violates the group’s policies, “we take immediate steps to rectify the situation as we did here.”

::

The Election Integrity Project and the Institute for Fair Elections promote themselves as nonpartisan, but neither is apolitical and both have strong ties to the California Republican Party and conservative Republican organizations nationwide.

The two ran for years on shoestring budgets but reported a surge of $840,000 in donations after 2016, the year then-President Trump and his advisor Roger Stone branded “stop the steal” as a way to motivate and mobilize supporters. The Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation, which has supported election watch organizations nationwide, gave $25,000 to the Election Integrity Project, according to the foundation’s tax filings. But the sources of the bulk of the remaining donations remain undetermined.

In 2017, Malcolm McGough, the head of volunteer operations for Trump’s 2016 campaign in California, became chief executive of the Election Integrity Project and ramped up allegations of illegal voting. He announced a partnership with conservative legal group Judicial Watch to sue Los Angeles County and California in an attempt to force purges of voter rolls.

The suit was settled after a U.S. Supreme Court ruling on a similar challenge in another state, requiring counties to review long-inactive registrations — a process Los Angeles County said resulted in the removal of 44,000 names in 2020. Activists contend it is not enough and seek removal of millions of voter names.

Meanwhile, the Election Integrity Project’s reports show it began forwarding its poll observer reports to the conservative Landmark Legal Foundation, an anti-immigration group that had announced a focus on hunting for noncitizen voters in California and sought to enlist the support of Trump’s Department of Justice.

McGough credited the Election Integrity Project’s activist turn to Randy Berholtz, a San Diego lawyer who now serves as secretary of the California Republican Party and has publicly promoted the election watch organization. Berholtz hung up the phone when a reporter asked about his association with the organization.

Also in 2017, Dunsmore, a Republican fundraiser, stepped in as president of the Institute for Fair Elections, filling out a board stacked with Republican party operatives.

Among its most recently reported directors are Ed Rollins, chairman of a national pro-Trump political action committee; Charles Bell, the state Republican Party’s general counsel; and David Ellis, a longtime Republican campaign consultant.

A former director has had his own brush with allegations of election irregularities. Scott Baugh, now a GOP campaign consultant, won election to the state Assembly in 1995 when Republicans placed one of his longtime friends, a Democrat, on the ballot as a decoy candidate to split the Democratic vote. Four GOP activists, including the wife of a congressman, pleaded guilty in the scheme; related criminal charges against Baugh were eventually dropped.

For years the institute audited voter registration lists in order to press county election officials to scrub their rolls, including of “ghost voters” who went eight years without casting a ballot.

Under Dunsmore’s leadership, the institute adopted more aggressive tactics. In 2018, the organization mailed some 652,000 postcards — ostensibly about a gas tax — to voters in targeted areas of seven counties and sent registrars the names of those whose mail could not be delivered, alleging the voters were not at the official addresses. The institute also sued Orange County in a failed attempt to force election officials to use jury lists to look for noncitizen voters.

A Times analysis shows the postcards in Orange and San Luis Obispo counties focused on ZIP Codes where Republicans faced strong challenges, including a congressional seat that wound up being won by a Democrat.

Dunsmore said her goal in focusing on areas with close races was to find fraudulent voters.

“We worked off the premise that you’re going to experience more voter activity in areas where there are more competitive races,” Dunsmore said.

Orange County elections officials confirmed they used Dunsmore’s postcard records to initiate removal procedures against voters, saying the U.S. Postal Service had verified the mail was undeliverable.

Registration records provided by San Luis Obispo County elections officials showed many of the voters flagged as suspicious were members of the military. Others had changed their postal address, not their residence.

“If we had inactivated them, they could have been disenfranchised in future elections,” said county registrar Tommy Gong.

The next year, the institute recruited volunteers, including members of a Republican women’s club, to call 11,000 inactive voters in Orange and San Bernardino counties, asking whether they intended to vote in the presidential primary eight months away but documenting those who had moved or, more often the case, whose numbers no longer worked.

In a letter to Orange County’s registrar, Dunsmore also characterized the records as indicating voters who were not citizens, though no such information was contained in the documents that were sent by her group to the county and were reviewed by The Times.

The phone bank and gas tax postcard campaigns together identified more than 20,000 voters to be investigated, spread across political parties.

“It wasn’t an effort to be partisan,” Dunsmore said. “There’s no data out there that suggests there’s more fraud amongst Democrats and Republicans. … You have to treat them as if they’re all the same.”

The institute’s work examining voter registration rolls provided ammunition for a Washington Post opinion piece in February 2020 by conservative radio host Hugh Hewitt that asked, “Can America safeguard the vote?” It also was used by Fox News host Tucker Carlson to allege Republicans lost Orange County congressional seats because of fraud.

Both pointed to claims by the institute that it found multiple people registered at a dog park.

Except it wasn’t true.

The list Dunsmore’s organization sent Orange County included scores of voters at a Laguna Beach address that when viewed in Google Maps appeared close to the city dog park. But the address is the city’s emergency housing shelter, adjacent to the park. Other mass registration sites flagged by the institute housed college students, priests and nuns.

Dunsmore is now working as campaign manager for Rescue California, a political committee that raised the vast majority of money behind the recall campaign. She said there has been no crossover between those activities and her work for the institute. She said she had put the Institute for Fair Elections on hiatus to focus on the recall.

::

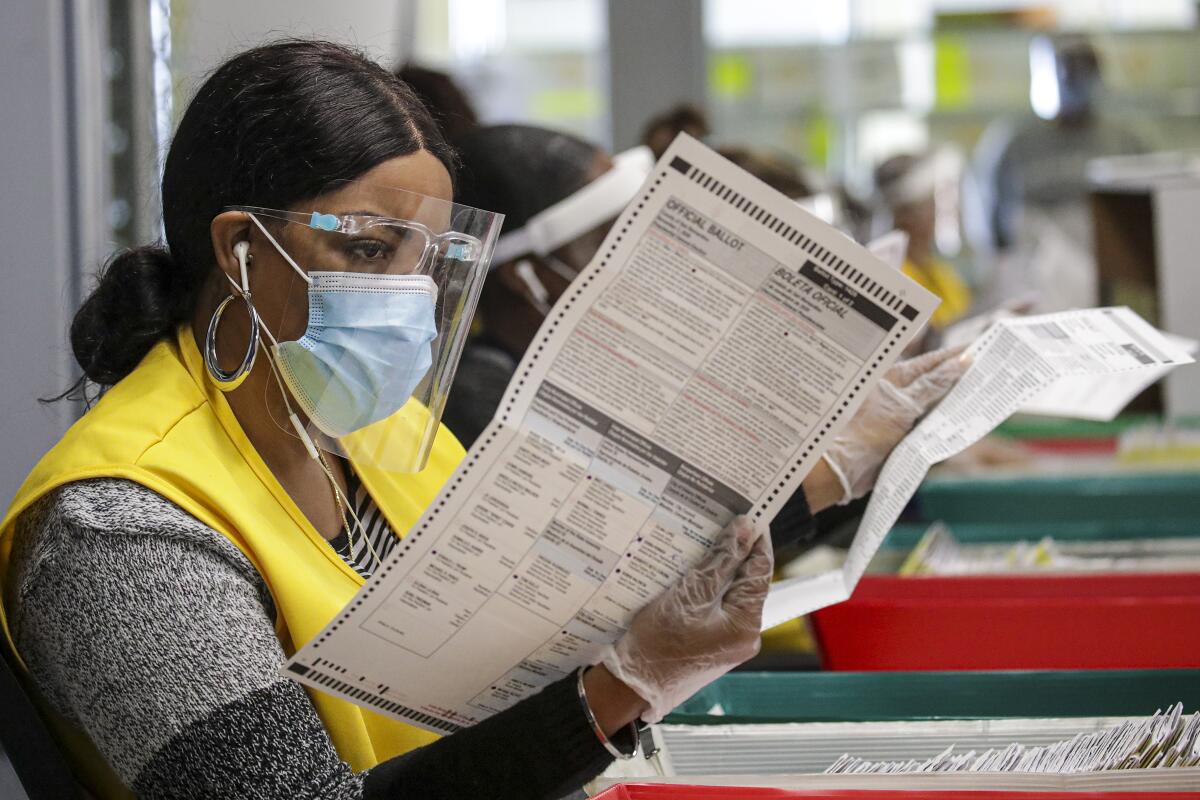

The expansion of voting by mail has provided the Election Integrity Project with an unprecedented chance to challenge votes by focusing on the envelopes ballots arrive in.

Election workers are required to check the signature on the outer envelope against those on file for the voter. The Election Integrity Project’s volunteer reports and the organization’s lawsuits show a pattern of not only watching signature checks but objecting when observers believe signatures don’t match and a ballot should be thrown out.

California law sets a high burden of proof to those challenging votes, because voters are not present to defend themselves. But election officials interviewed by The Times said challenges by Election Integrity Project observers to signatures subjected those ballots to a higher level of scrutiny.

The organization took Ventura County to court last year seeking an emergency order that would have allowed observers to stand close enough to be able to read ballot signatures. A judge refused, deciding that the real intent was not to observe the processing of ballots but to challenge votes, something he said is not legal.

Another judge in Fresno County refused the Election Integrity Project’s demand to review ballot envelopes after the election — again to check signatures — ruling those are confidential.

Undaunted, the organization’s presence in November at voting centers where mail ballots were processed at times exceeded that of candidate campaigns and political parties. Check-in logs provided by San Diego County show 275 of the 329 observers admitted to watch ballots being processed had come from the Election Integrity Project.

Volunteer reports filed in court show the frustration of its observers when they could not successfully challenge ballots.

“I have a feeling that California voted RED, but we will never know,” an observer in Orange County wrote, calling the electoral process a “sham.”

The Election Integrity Project joined the wave of conservative groups that went to court after the November election claiming fraud and seeking to invalidate the results. It modified the lawsuit in March to allege only the potential for fraud and seek an audit of California voting.

U.S. District Judge André Birotte Jr. this month dismissed the case. He ruled that the Election Integrity Project and its co-plaintiffs — 13 defeated Republican congressional candidates — could show no harm, and he rejected their claim that the state’s adoption of pandemic voting rules meant California was no longer a “Republic.”

A Republican activist in San Diego County recently told members of a local political club that the California Republican Party leadership has held monthly meetings since December with Paine in preparation for the recall, even as the state party launches its own poll watch campaign.

She urged party members to join the Election Integrity Project, calling it “an important part of the mission of the California Republican Party and Republican Party of San Diego.”

Other conservative and political organizations are also recruiting for the Election Integrity Project.

“Volunteers ask, ‘What can we do next?’” Mike Netter, a leader of the signature drive to recall Newsom, said on one of the organization’s webcasts this spring. With the signature drive done and the election certified, Netter encouraged them to remain “fired up” over the coming vote.

His advice: “Work with Linda and our groups together to monitor these elections, to make sure that the voice of the people is heard.”