Powerful, wealthy interest groups keep tight grip on California proposition system

SACRAMENTO — California voters were first empowered to govern by ballot measure in 1911. But it took almost seven decades and the anti-tax crusade of a cantankerous, fist-shaking businessman to reveal the political strength of a direct democracy tool that has come to redefine the state’s politics ever since.

What Howard Jarvis discovered in 1978 with Proposition 13 was that the public’s distrust of government was a kind of electoral rocket fuel that could carry almost any payload into orbit. It no longer took haggling with legislators in Sacramento to write a law. It took only a popular concept and — over the last two decades — enough money to wage a nonstop blitzkrieg of TV commercials and mailbox fliers.

On Tuesday, voters waded through a dozen propositions covering a variety of complicated policy ideas. Most were carefully crafted by powerful interest groups, often as much a solution to their problems as addressing an urgent public need.

“What this cycle showed, maybe more than any other, is that you can pay for a law if you don’t like something that’s going on,” Democratic political strategist Gale Kaufman said. “With brute strength, you can buy yourself virtually any law you want or defeat any law you want.”

Kaufman, a campaign consultant who’s been involved in a number of fierce ballot measure fights on behalf of labor unions, drew two particularly tough assignments this year: mounting the opposition campaign against Proposition 22, the app-based industry plan to write special rules for its drivers, and trying to persuade voters to ratify the Legislature’s end of cash bail, Proposition 25. Election returns show the efforts came up short.

In both campaigns, money tells an important part of the story.

Proposition 22 had a bank account before it had a blueprint. Uber and Lyft, joined later by DoorDash and others, set aside $90 million last summer — weeks before drafting an initiative — frustrated that state lawmakers wouldn’t include an exemption for their drivers in a far-reaching worker classification law, Assembly Bill 5.

By election day, the Silicon Valley companies had championed the most expensive ballot measure campaign in U.S. history. While not every political campaign with money wins, the large war chest for Proposition 22 helped it break through the noise in an election season in which voters were focused on the presidency and the pandemic.

The companies used a unique feature of California’s initiative process: its inflexibility.

“Backing a ballot initiative is a way to lock your own special deals and detailed preferences into the state Constitution or into initiative statutes, which are super-laws that often require another vote of the people to amend them,” said Joe Mathews, a longtime California journalist and a columnist for Zocalo Public Square in Los Angeles.

The rigid nature of California’s ballot measure system helps explain another 2020 initiative, Proposition 15, the most ambitious effort yet to rethink Jarvis’ vaunted Proposition 13 tax rules. Liberal activists, bankrolled by public employee unions, wanted voters to remove commercial and industrial properties from the tax limits of the 1978 initiative. While the final vote tally won’t be known for weeks, returns show Proposition 15 coming up short.

Along the way, supporters and opponents doled out some $139 million — making it the fifth most expensive ballot measure campaign in state history — and the result appears to be a continuation of the status quo, even though decades of policy experts have suggested California’s tax structure could use an overhaul.

In most conversations about ballot measures, the talk turns to money. And in every election, the origins of direct democracy fade further into the background. Championed by then-Gov. Hiram Johnson in 1911, the power of the plebiscite was seen as a way for citizens to break the tight grip of the era’s most powerful California interest group, the Southern Pacific Railroad. Johnson’s inaugural address promised that those writing laws by voting would “prevent the misuse of the power temporarily centralized in the Legislature,” where railroad officials held sway.

But it is the well-funded interest groups, not citizens, who control the modern-day ballot measure process.

“It’s a bitter irony that the ballot initiative, a tool used all over the world to advance democracy, is used in California to short-circuit and cancel democracy here,” Mathews said.

With enough money, the same battles can be waged over and over again.

A half-dozen of this year’s propositions saw powerful groups returning to familiar topics. Three ballot measures — the effort to broaden a property tax break for seniors in Proposition 19, to expand rent control under Proposition 21 and to more tightly regulate kidney dialysis clinics in Proposition 23 — were slightly amended versions of measures rejected by voters in 2018. Proposition 20, which sought to tighten criminal justice rules voters had just loosened in 2014 and 2016, was defeated.

Only Proposition 19 appears to have won its second round with voters, after changes designed to help Californians who lose their home in a wildfire won the backing of the state’s firefighters union. And Proposition 24, a wide-ranging set of consumer privacy rules that won passage, was a reworking of a 2018 law ratified by the Legislature.

Perhaps the newest approach by moneyed interests is to think about not just writing laws through the passage of an initiative, but blocking laws by filing a referendum.

The referendum — the power of voters to erase a law enacted by the Legislature and governor — has long been the forgotten sibling in California’s direct democracy family. Only 94 referendum measures have been filed to block a state law since 1912, compared to more than 2,000 proposed initiatives.

But if backers of a referendum gather enough voter signatures, the challenged law is put on hold until voters weigh in on election day — even if the next election is two years away. The industry that produces plastic bags did that in 2014, and failed to persuade voters to overturn a ban on the products in 2016.

The bail bonds industry played the same card in 2018, after then-Gov. Jerry Brown signed a law banning the use of cash bail for those accused of committing a crime. The result was Proposition 25, a law voters scuttled in Tuesday’s election.

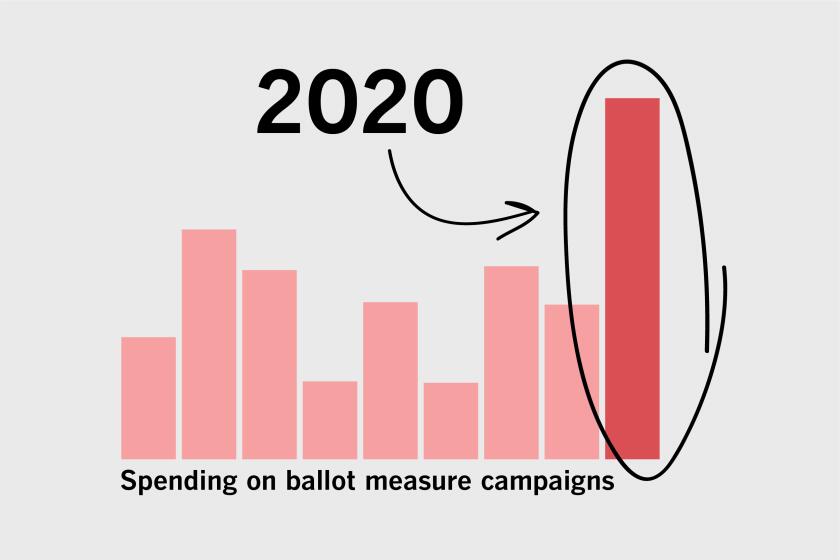

In all, political action committees spent more than $785 million to support or oppose the 12 propositions on the November ballot, according to an analysis by The Times.

And another referendum could be on the horizon: Senate Bill 793, a law signed in September by Gov. Gavin Newsom that bans the sale of flavored tobacco in California, is being challenged by the tobacco industry. Their effort, if it gathers enough voter signatures on a referendum petition by the end of this month, will suspend SB 793 until election day in November 2022.

“I think there’s going to be a lot of these in the years to come,” said Kaufman, who oversaw the effort to preserve the law banning cash bail.

The future of big ballot measure campaigns all depends on voters. The more they approve the proposals, the more well-funded groups will see the system as an alternative to the slower, consensus-focused process in the Legislature. Surveys conducted by the nonpartisan Public Policy Institute of California since 2000 have consistently found strong public support for direct democracy.

In 2013, the institute’s researchers noted that 60% of likely voters in one survey said laws enacted through the ballot are probably better than the ones that originate in Sacramento.

“Voters get exhausted by it, but they get over it,” said Fiona Hutton, whose statewide public affairs agency worked on the campaign in support of Proposition 14, the $5.5-billion stem cell research bond that had a narrow lead in early returns. “We just push reset and we start all over again in two years.”