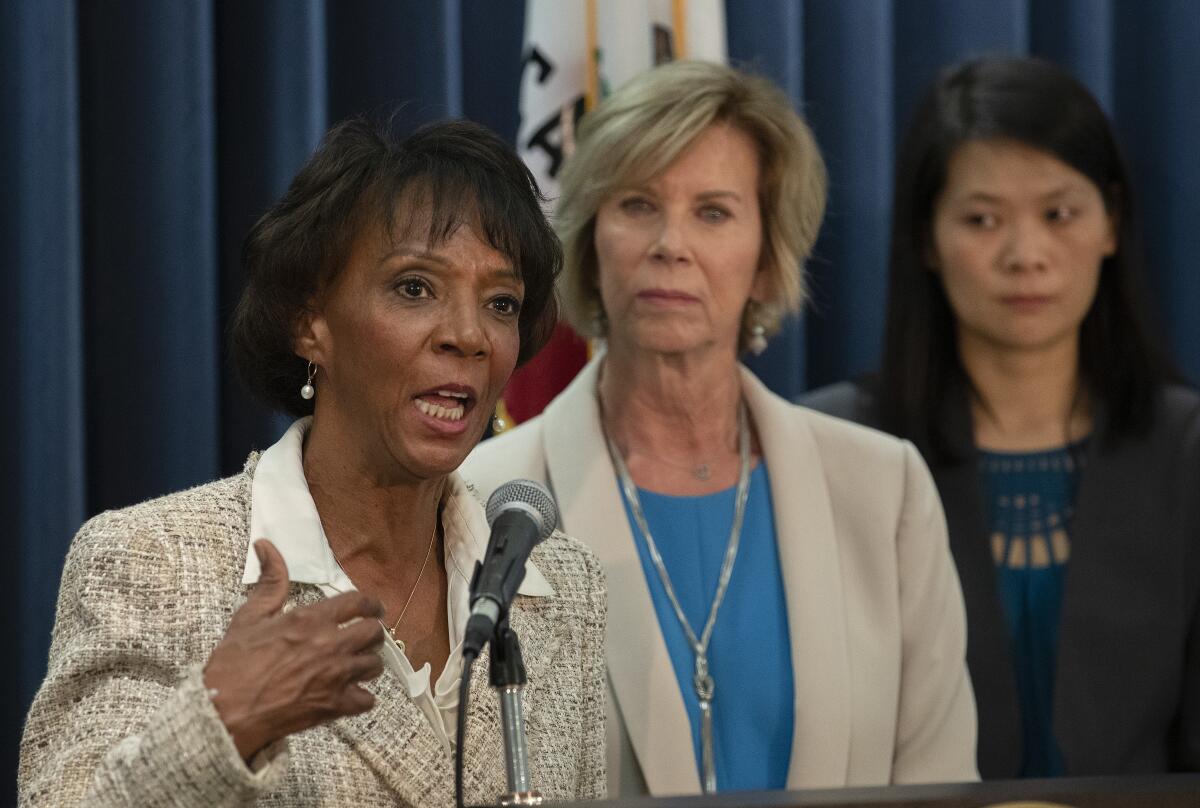

Jackie Lacey is a longtime champion for mentally ill defendants. But do her reforms go far enough?

After years of frustration with a criminal justice system that seemed to favor incarceration over treatment of mentally ill defendants, Mark Gale said he found an ally in Los Angeles County Dist. Atty. Jackie Lacey.

Gale, whose son suffers from schizophrenia and had been arrested at least twice in the 2000s, says Lacey deserves credit for helping to conceive many of the programs that offer services to mentally ill defendants in L.A. County today.

A task force convened by Lacey led the Board of Supervisors to pump $120 million into housing and resources for the mentally ill, part of a broader attempt to divert such defendants from the jail system that includes the creation of a countywide Office of Diversion & Re-Entry. The district attorney’s office under Lacey has also launched or broadened a number of alternative sentencing courts that have benefited mentally ill defendants and trained thousands of law enforcement officers in crisis intervention.

“In terms of mental health and reform, none of this would have happened had she not convened the county,” said Gale, who is also the criminal justice coordinator for the National Alliance on Mental Illness’ Los Angeles chapter.

Lacey has often touted her record on mental health as she tries to fend off a November challenge from former San Francisco Dist. Atty. George Gascón, who has run to her left as a criminal justice reformer and champion of reducing incarceration for a broad range of offenses.

But some critics say Lacey’s programs are not expansive enough and that many line prosecutors working in the nation’s largest local court and jail system have resisted their use.

The county’s nine alternative sentencing courts — which aim to divert a wide range of nonviolent offenders including veterans, homeless defendants and those suffering from mental health or substance abuse issues from jail — processed 3,935 defendants between 2014 and February of this year, according to data provided by the district attorney’s office.

Defense attorneys argue that’s a drop in the bucket for an office that filed, on average, more than 100,000 misdemeanor cases each year in the same time frame, many of which they said involve alleged criminal behavior that would be better deterred by therapy.

The county’s Office of Diversion and Re-Entry also provided “permanent supportive housing” to about 2,910 homeless or mentally ill defendants since its creation, Lacey’s office recently reported. That number includes people who served jail time or had been sentenced to probation as a condition of entry into the program.

A Rand report published in January, meanwhile, found that more than half of all mentally ill people held in L.A. County jails would have been appropriate candidates for diversion programs.

“In theory, these laws, specifically mental health diversion, are all very good and progressive and noble,” said defense attorney Damon Alimouri. “But in my experience, and in speaking with my colleagues, both public defenders and private criminal defense attorneys, the D.A.’s office by and large vigorously opposes defense applications or requests for alternative sentencing or mental health diversion.”

Some have also criticized Lacey’s prosecutors for repeatedly opposing applications for diversion filed under a new state law that allows judges to order treatment for defendants whose offense was driven largely by their mental disorder. The district attorney’s office has received 840 such petitions; 280, roughly 33%, have been granted, said Deputy Dist. Atty. Gilbert Wright, who leads the mental health unit.

Lacey says the diversion numbers tell only a fraction of the story. Programs born out of the countywide mental health advisory board she convened in 2015 have also provided treatment to roughly 2,700 defendants found incompetent to stand trial, the D.A.’s report said. Those defendants would have otherwise languished in jail until being restored to competency. More than 8,000 Los Angeles police officers and sheriff’s deputies have also been trained in de-escalation or crisis intervention through the district attorney’s office, the report said.

Lacey said access to diversion programs is stymied by limited resources.

“A lot of the people recommended for pre-trial diversion are folks that have stabbed somebody, or have demonstrated in the instant crime that there’s a danger there. So that’s why we need more places to safely divert,” she said. “If the Department of Mental Health would get on board, quickly, we would have more places. You would see those diversion numbers increase.”

Lacey says she first became focused on improving dealings with mentally ill defendants as a line prosecutor, after seeing one too many cases in which someone suffering a mental health episode wound up in jail.

She recalled that in 2011, she was contacted by a woman whose daughter was arrested for carjacking while experiencing a mental health crisis. The woman was having delusions that someone was chasing her in Los Angeles, so she jumped into a vehicle and tried to flee. Despite having no criminal record and clearly being in crisis, the woman was forced to plead guilty to a crime in order to gain access to treatment, according to Lacey, who said the case has always haunted her.

“She was a very bright person, a bright college student. I always thought there should be another alternative to someone like that,” Lacey said. “I actually contacted her way after the case, and she asked me, what am I supposed to tell a future employer?”

But Nikhil Ramnaney, the head of the union representing L.A. county public defenders, said prosecutors frequently object to mental health diversion petitions on public safety grounds, regardless of the facts of a case.

He recently represented a schizophrenic Long Beach resident who had been charged with elder abuse for attacking his mother. The two got into an altercation during an argument over the man’s refusal to take his medicine, and his mother suffered a broken nose.

The defendant was declared incompetent to stand trial. While in a state hospital, he resumed his regular medical regimen and his symptoms abated, Ramnaney said. But when the case returned to court, a prosecutor opposed diversion, citing the risk to his mother, and insisted on a plea that would result in prison time, Ramnaney said.

Ramnaney said the defendant’s mother was opposed to the prosecutor’s position and had initially hesitated even contacting police for fear of how her son’s case might proceed through the courts.

“There’s no question about the necessity or that [treatment] is effective. We know that when he’s on his medication, he does better. We know that in a structured residential setting, he does better. We know that’s what the victim wants,” Ramnaney said. “But they want prison … what is the value of prison in this case?”

Alimouri said he represented a schizophrenic graduate student who last year began to suffer delusions of a romantic connection with one of his professors. Court records show the man was arrested for violating a restraining order and charged with felony stalking when he approached the woman at her office, though the case was dismissed at a preliminary hearing.

Prosecutors later refiled the case. Alimouri’s diversion petition was opposed by a line prosecutor before being approved by a judge. Even though Alimouri’s client managed to receive diversion, he said the constant objections make him wonder how many other such petitions are granted over the wishes of the district attorney’s office.

In an interview, Lacey suggested the prosecutor in Alimouri’s case should not have opposed diversion. She and others are trying to shift a culture within the office that had long been too focused on convictions as a metric of success, she said.

“I’m leading a change, a national change, where we look at these things differently and do some things different and it takes time,” she said. “You don’t necessarily dictate a change of heart, but you lead people.”

Though he admits there may be room for improvement, Gale believes Lacey has proved herself an effective change agent when it comes to the county’s approach to mental health diversion. Gale’s son began to suffer from bipolar disorder as a teen and had been arrested twice before Lacey was elected.

Outside of a small program run by the county, Gale said he doesn’t like thinking about the limited options his son once faced.

“There was nothing. Nothing. There was jail, there was prison. There was acquittal,” he said. “That was it.”