La Niña is back. What does that mean for California’s drought?

La Niña conditions were observed in the Pacific Ocean last month, and there is a 75% chance the weather pattern will persist through the winter, forecasters with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration said.

A La Niña climate pattern has been slowly building over the summer, and now we’re in “strengthening La Niña territory,” climatologist Bill Patzert said Thursday.

What does that mean for California and the Southwest?

“Typically speaking, La Niñas turn out dry for Southern California, and El Niños turn out wet. But not always,” Patzert said.

La Niña is the cool phase of a climate phenomenon called the El Niño-Southern Oscillation, often referred to as ENSO. Its warmer, better-known, sibling is known as El Niño, and there is third, neutral phase between those two on the continuum.

Specific conditions for the ocean and atmosphere must be present for an El Niño or La Niña weather pattern.

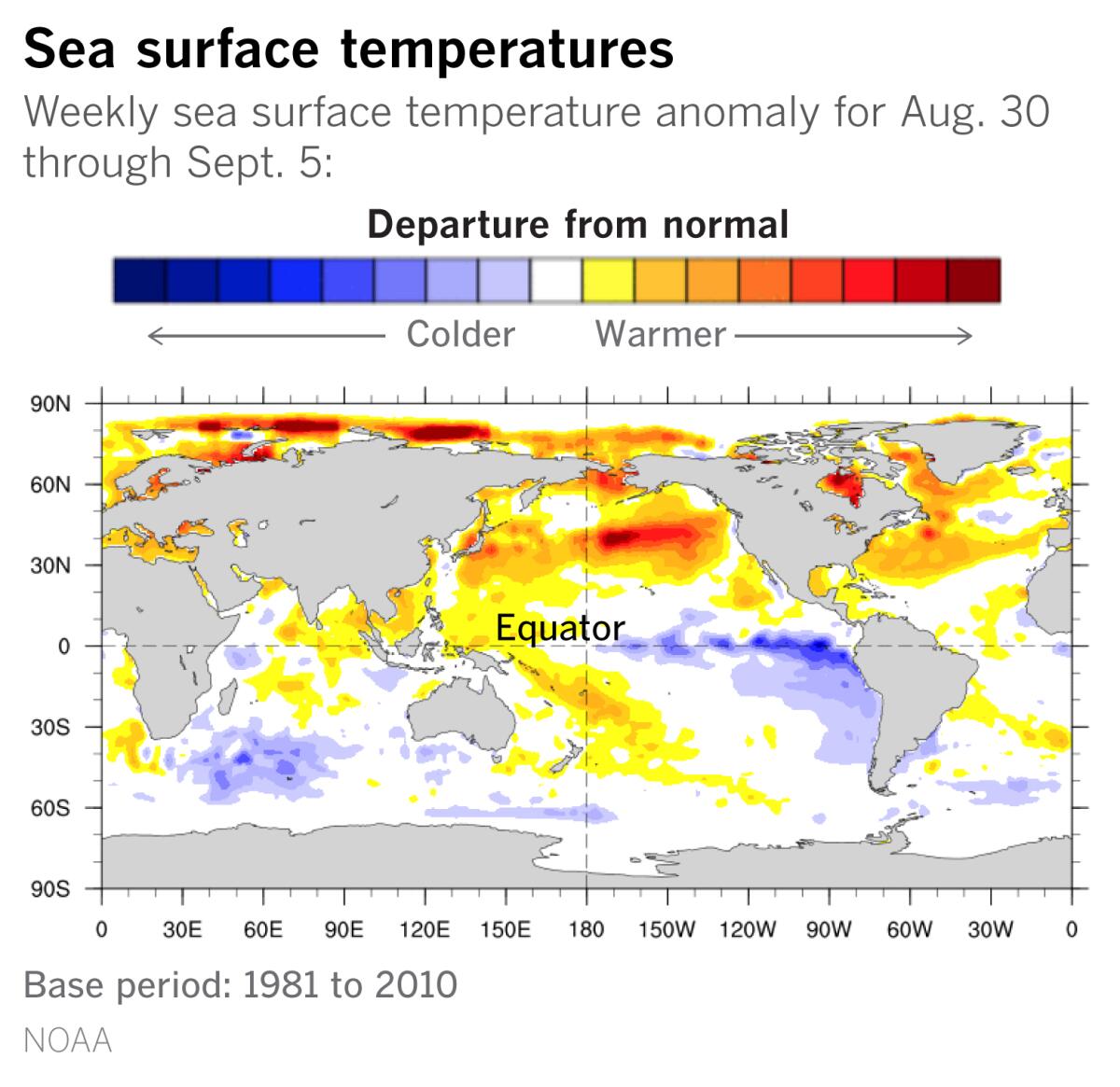

In the case of La Niña, below-average sea surface temperatures occur in the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean. Easterly winds over the equator strengthen, and rainfall usually decreases over the the central and eastern tropical Pacific and increases over the western Pacific, Indonesia and the Philippines.

“La Niñas are never a sure bet,” Patzert said.

He points to downtown Los Angeles to illustrate how rainfall totals can still be above average in weak La Niña years. The 143-year annual average rainfall for downtown L.A. is 14.93 inches. In 2001, 17.94 inches of rain fell, and in 2017, 19 inches fell. Both were weak La Niña years.

“La Niña isn’t the only player in the rainfall prediction game,” said Patzert, citing numerous global climate factors.

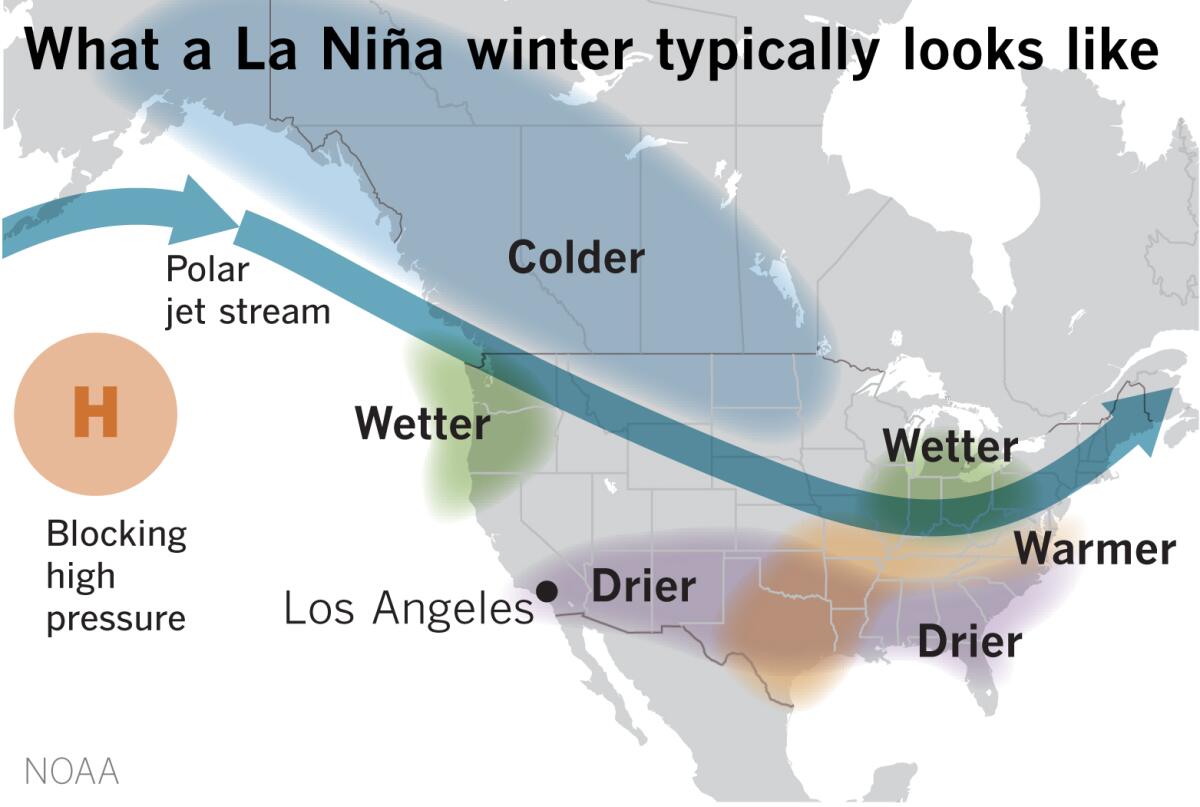

Typically, though, La Niñas are often associated with colder, stormier-than-average conditions and increased precipitation across the the northern parts of the U.S., and warmer, drier and less stormy conditions in the southern portions of the country.

If this scenario unfolds, it would exacerbate drought conditions in Arizona, Colorado, Utah and California and worsen the wildfire outlook for the remainder of 2020 and into 2021.

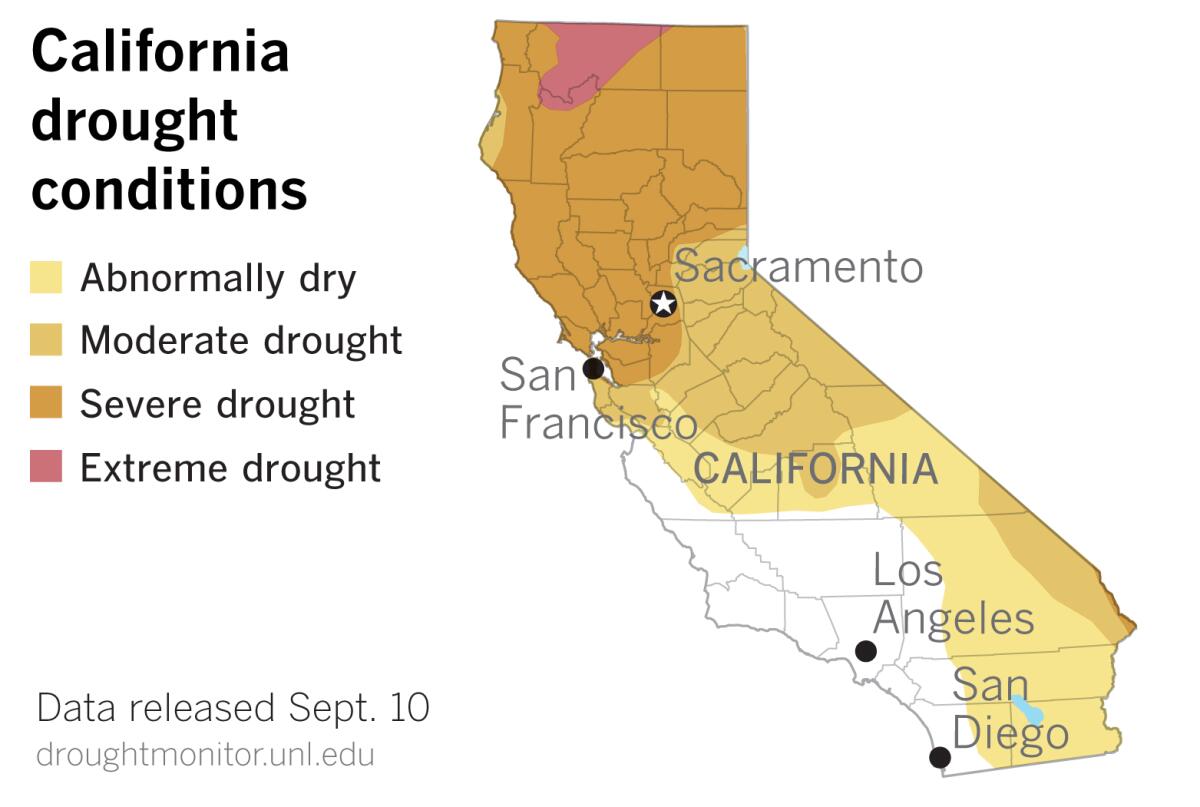

The most recent U.S. Drought Monitor data, released Thursday, shows more of California slipping into drought. In the last week, an additional 1.2% of the Golden State was identified as being in severe drought.

“The Drought Monitor may not show it, but those of us who are living through the severe fires know that Central and Southern Coastal California are bone dry and incendiary,” Patzert said.

Most of San Bernardino, Riverside, half of San Diego and all of Imperial counties are considered to be abnormally dry. Most of Northern California above the Bay Area is in severe drought, and a portion of the state along the Oregon border, mainly in Siskiyou County, is in extreme drought. The northern Sierra region, where the state’s biggest reservoirs are located, is in severe drought.

The potential that a dry winter may result from La Niña is not good news for a state parched by drought and suffering the worst wildfire season on record.

“The dice are loaded for drought, but it’s not a sure thing,” Patzert said. “It’s still a crap shoot, but firefighters, water managers and farmers would be wise to be prepared.”