Manhattan Beach was once home to Black beachgoers, but the city ran them out. Now it faces a reckoning

Anthony Bruce could barely talk about the beach that bears his family’s name without feeling a sharp pain, a tug at the heart.

More than a century ago, his ancestors had turned this small corner of Manhattan Beach into a popular resort — one where Black people could dip their toes in the sand and bask in their own slice of the California dream.

But their white neighbors, in this very white town, ran them all away.

“This is our legacy, this beach,” Bruce said. “It has haunted my family for ages.”

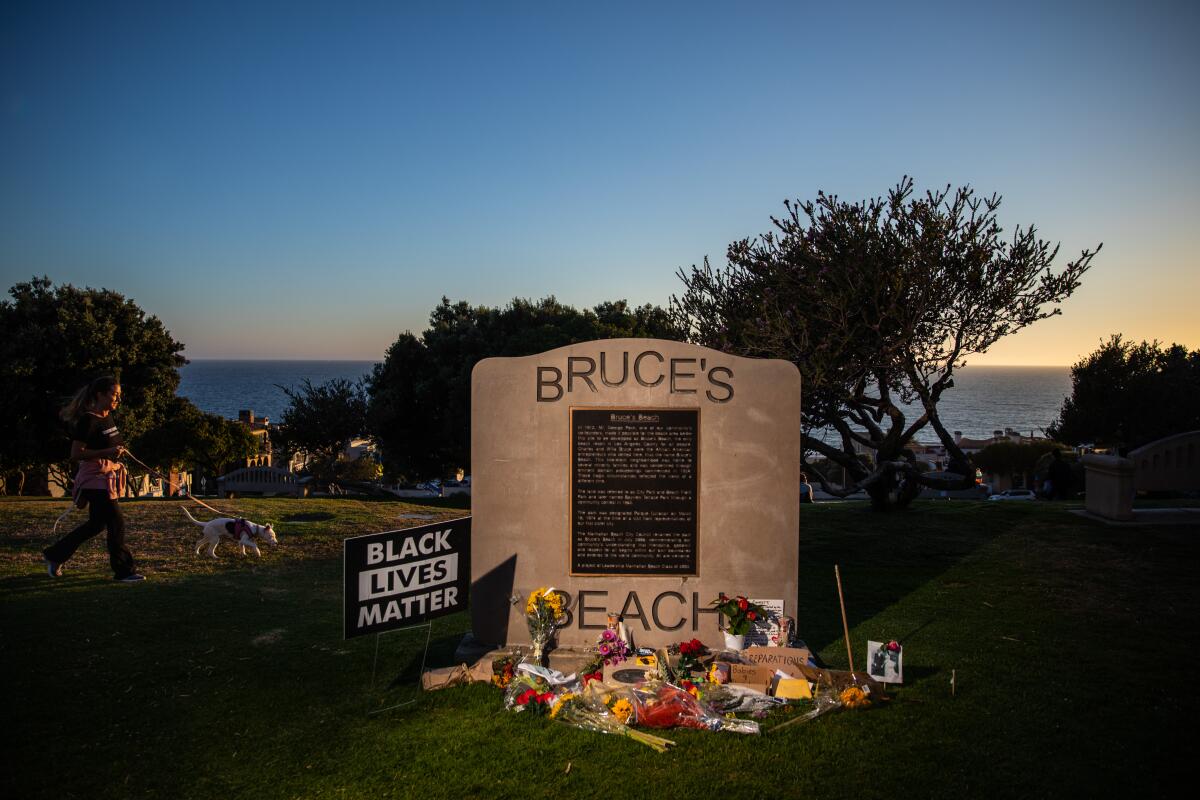

Today, most see Bruce’s Beach as a pretty park with jasmine and coastal live oak overlooking the sea.

In this affluent town of 35,000 — known for its manicured homes, the community fair, the Strand by the sea — few know of this racist past. Others would prefer to gloss over the uncomfortable details in a community where Black residents make up less than 1% of the population.

But as protesters across the nation continue to fill the streets calling for a more equitable society, a new generation is demanding that the city atone for past wrongs. Like the many towns, institutions and universities that have been forced into similar reckonings since the death of George Floyd, Manhattan Beach must confront its own history.

The truth, after all, was buried for generations — then rewritten over the years to fit preferred narratives.

“Bruce’s Beach was an injustice in our town’s history,” said Gary McAulay, president of the Manhattan Beach Historical Society. “The facts are tragic enough, but in the nearly 100 years since then, the facts have often been corrupted in the retelling.”

::

The story of Bruce’s Beach begins with the Tongva, who roamed the dunes and gathered seafood along this windy stretch of coast. Then came the Spanish, and by the early 1900s, George Peck and others developed what is known today as Manhattan Beach.

In 1912, Willa Bruce purchased for $1,225 the first of two lots along the Strand between 26th and 27th streets. While her husband, Charles, worked as a dining-car chef on the train running between Salt Lake City and Los Angeles, Willa ran a popular lodge, cafe and dance hall — providing Black families a way to enjoy a weekend on the coast.

Many referred to this area as Bruce’s Beach. A few more Black families bought and built their own cottages by the sea. A community was born.

“They were pioneers. They came to California, bought property, enjoyed the beach, made money,” said Alison Rose Jefferson, a historian and author of the book “Living the California Dream: African American Leisure Sites during the Jim Crow Era.” “They did what every other Californian was doing during that time.”

But white neighbors resented Bruce’s growing popularity. Tires were slashed. The Ku Klux Klan purportedly set fire to a mattress under the main deck and torched a Black-owned home nearby. Fake “10 minutes only” parking signs were posted to deter Black out-of-town folk. To reach the ocean, visitors had to walk an extra half mile around property owned by Peck, who had lined it with security and “No Trespassing” signs.

This hostility was not uncommon at the time. Another popular area in Santa Monica was referred to as the Inkwell. In Huntington Beach, the Black-owned Pacific Beach Club mysteriously burned the day before it was scheduled to open.

When harassment failed to drive the Black beach-going community out of town, city officials condemned the neighborhood in 1924 and seized more than two dozen properties through eminent domain. The reason, they said, was an urgent need for a public park.

The Bruces and three other Black families sued, citing racial prejudice, according to Robert Brigham, a longtime resident and historian who, in 1956, sought to tell the real story of Bruce’s Beach in his master’s thesis at Fresno State College. The Bruces sought $120,000 in compensation — $70,000 for their two lots and $50,000 in damages. Another couple asked for $36,000.

After years of litigation, the Bruces received $14,500. The other families, Black and white, received between $1,200 and $4,200 per lot.

Most found other property in Manhattan Beach, but the city made it impossible for the Bruces to move their seaside business anywhere else in town. So they packed up and went inland, where they served as chefs for other business owners for the remainder of their lives.

“The part that entrenches this whole idea of white privilege in the law and in our culture, that people don’t realize the full effect, is this idea of generational wealth,” said Effie Turnbull Sanders, the California Coastal Commission’s environmental justice commissioner.

She noted how eminent domain was once also used to take property from interned Japanese Americans and to dispossess Latino families of their properties to build a public housing project that ultimately became Dodger Stadium.

“It is mind boggling to think about how many opportunities are missed when the government intercedes to prevent certain people from building wealth,” said Turnbull Sanders, who has worked for 20 years in land-use law. “Generations of wealth building have been eliminated for so many folks of color in California history.”

Bruce’s Beach was razed and remained vacant for decades.

In the 1950s, city officials began to worry that family members might sue to regain their land unless it was used for the purpose for which it had been originally taken. City Park was born, and later renamed Beachfront, then Bayview Terrace Park. In 1974, it was named after a sister city in Mexico, Parque Culiacan.

By 2006, after a summer of intense debate, the City Council voted 3-2 to rename the beach after the Bruce family — largely because of an appeal by Councilman Mitch Ward, the city’s first Black elected official.

But the commemorative sign, many say, reinforced the white way of seeing the world: “In 1912, Mr. George Peck, one of our community’s co-founders, made it possible for the beach area below this site to be developed as Bruce’s Beach, the only beach resort in Los Angeles County for all people,” the statement begins.

Anthony Bruce, many generations later, says this history continues to tear his family apart. His grandfather Bernard, born a few years after the condemnation, was obsessed with what happened and lived his life “extremely angry at the world.”

“How would you feel if your family owned the Waldorf and they took it away from you?” Bernard said in a 2007 interview with The Times. Growing up in South L.A., he said when he told school friends that his family once owned a beach, they would laugh at him.

Bernard’s marriage suffered, and he wanted Anthony’s father to become a lawyer so that he could keep fighting to right these wrongs, Anthony said. Instead, his father took the kids and left California.

Today, Anthony, 37, is a security supervisor in Florida and teaches English online. He’s the only Bruce who can manage to talk publicly about the beach, but even he feels worn out. He’s heartened by the new movement of people championing the cause.

“People are out there because they want to see justice too,” he said. “They know that what happened to Charles and Willa is still happening every day in different parts of the world.”

::

Kavon Ward, who moved to Manhattan Beach three years ago with her newborn daughter, said she knew she wasn’t welcome when a woman at Polliwog Park asked which family she was nannying for. At the local Ralph’s, she was called a terrorist for wearing a Black Panthers T-shirt. The local Facebook group for moms, she said, kept deleting her posts about Black Lives Matter.

But Ward was appalled when she heard about Bruce’s Beach. She and a few moms started their own group, Anti-Racist Movements Around the South Bay, and did everything they could to shake their neighbors, city leaders and state legislators into action. They reclaimed the park as a space to honor Black lives — including a Juneteenth celebration and memorials for Breonna Taylor and Emmett Till.

“It’s like: You kicked the Bruces out, but you’re not going to run me out,” Ward said. “So if I’m not leaving, I’ve got to fight to make it better.”

Another resident started a petition, which has gathered 9,500 signatures, demanding that the city make a new plaque, issue a public statement and give the land back to the Bruce family “and provide restitution for loss of revenue for 95 years and monetary damages for the wanton violation of their civil rights.”

These demands have forced an uncomfortable conversation for many in the community.

In an editorial in the local Easy Reader News, Russ Lesser, a 76-year-resident of Manhattan Beach who served as mayor in the 1980s, questioned how returning the land would even work.

The park itself, he noted, was not the two parcels that the Bruces actually owned down by the Strand, where the county lifeguard station sits today. Current fair market value for the entire area would be at least $75 million, he estimated. How would taxpayers come up with this money?

“What happened was wrong,” he said. “I have no problem with teaching the history of Bruce’s Beach, but if you only teach what happened nearly one hundred years ago, and do not teach about the progress we have made in those hundred years, then it seems to me the goal is to create hatred and divisiveness.”

City Mayor Richard Montgomery said he is open to redoing the plaque and has said as early as 14 years ago that an apology was long overdue.

“We all agree there were some things that happened in the past that we’re not proud of,” he said. “But the temperament and the people and the times have changed. We’re a different city today than we were 100 years ago.”

As for the demand for restitution, Montgomery said the city needed to first get the facts straight before deciding how to proceed. The City Council is seeking historians, he said, to teach the community what really happened.

Duane Shepard Sr., a 62-year-resident of South L.A. and designated Bruce family representative, said he’s been building a case and researching which parcels, and how many, Charles and Willa actually owned.

Shepard, a Bruce cousin on his mother’s side, imagines the land could be used for a historical center, the money perhaps used to establish a scholarship foundation. He smiled as he described a reunion held at the park in 2018, where about 150 family members had gathered for the first time.

“It was very spiritual for us to come together as a family,” said Shepard, who is a Pocasset Wampanoag chief and tribal elder from his father’s side. “I declared the land sacred that day and promised that I would do everything I could in the world to get justice for our family.”