The Dodgers were still in Brooklyn and Dwight D. Eisenhower was still in the White House the last time Southern California went this deep into the summer without a Major League Baseball game.

For Conrad Munatones, then a 20-year-old catcher from East Los Angeles, the big leagues were an East Coast thing, like Broadway plays or Philly cheesesteaks.

“When someone said the Brooklyn Dodgers, I thought that meant Brooklyn Avenue,” he remembered.

Two minor league teams played in Los Angeles, but to Munatones, baseball meant Sunday doubleheaders at Belvedere and Evergreen parks, where neighborhood legends made their names playing for teams like Eastside Beer, Ornelas Food Market and the Carmelita Chorizeros. The games drew hundreds of people to the parks after church to sit on uncomfortable wooden bleachers or on blankets in the grass as mariachis played and carne asada sizzled.

“For Mexican Americans in the postwar era, next to the Catholic Church, barrio baseball was both the centerpiece and the heartbeat of their community,” said Samuel O. Regalado, a Cal State Stanislaus history professor who has written extensively on the subject. “For the players, both U.S.-born and migrants, the games were a transnational platform by which they could achieve a level of respect and local notoriety that, outside of the barrios, was rarely afforded to them.”

For players like Munatones, who signed with the Dodgers two months after the team moved from New York in 1958, baseball was never better than on those warm summer afternoons in East L.A.

“The interest was total in that community because that’s all we had,” said Munatones, now 83 and living in San Dimas. “We were given the opportunity to perform in front of good-sized crowds that loved baseball and didn’t have the money to buy tickets for the [minor league] Angels or the Hollywood Stars.

“It was quite a thing. Most of these people were laborers. They were given a Sunday to enjoy so they would do it as a family.”

Evergreen Park, now Evergreen Recreation Center, is temporarily closed, a victim of the COVID-19 pandemic that also delayed the start of the Major League Baseball season until Thursday. But the memory of how baseball once thrived there hasn’t been forgotten, not by those who played or cheered them on.

::

“You’d get standing room only when Carmelita was playing. They were just something else.”

— Conrad Munatones, on the Chorizeros

Minor league baseball ruled in Southern California for the first half of the 20th century, but the Stars played at Gilmore Field in the Fairfax district on what is now CBS Television City and the Angels at Wrigley Field in South Los Angeles. To the people of East L.A., the teams might as well have been in South America.

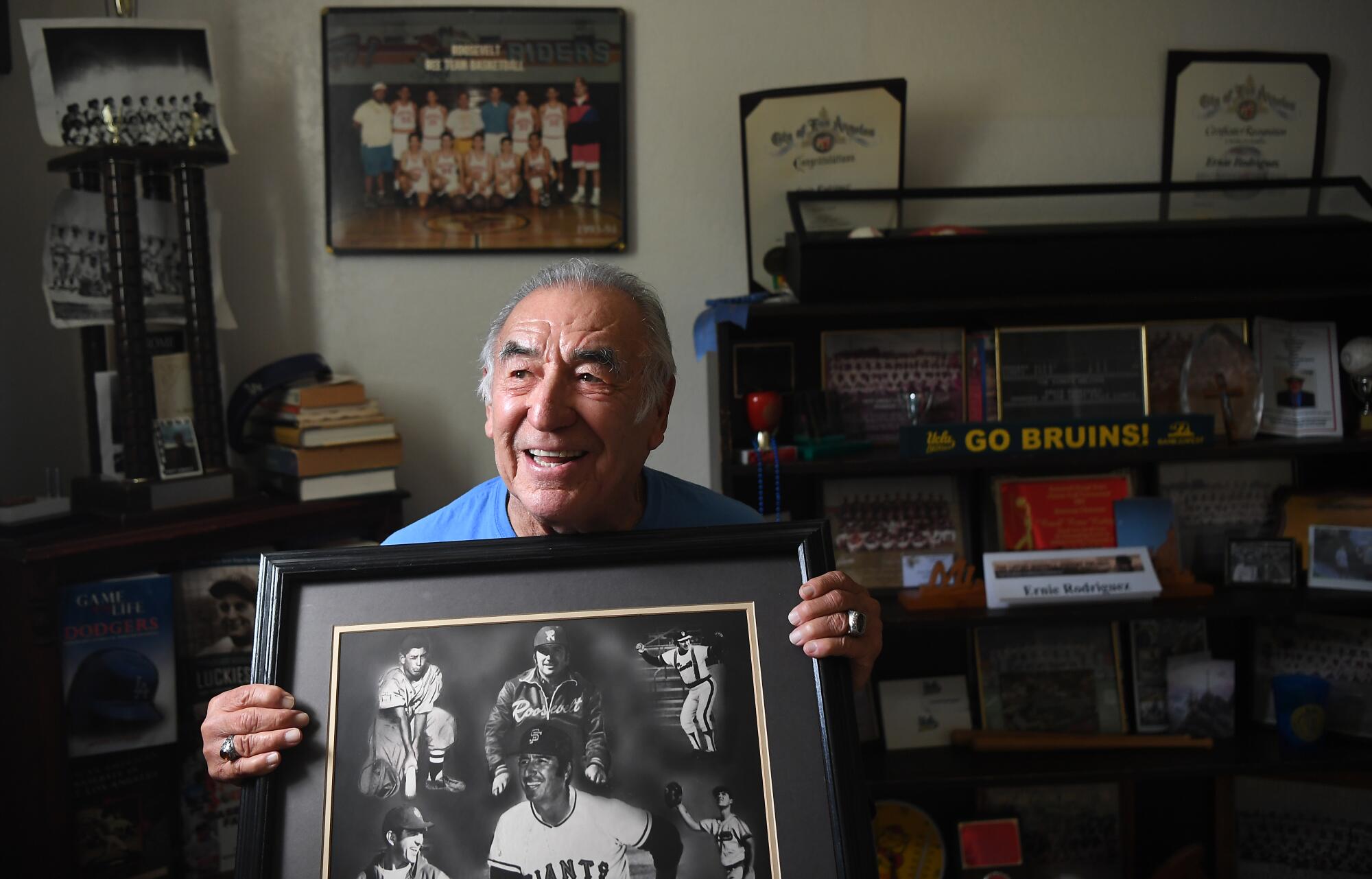

“A lot of people couldn’t get to Wrigley Field or Gilmore Stadium. So the Sunday leagues became very big in the Boyle Heights community,” said Ernie Rodriguez, an outfielder who debuted with the Chorizeros — or sausage makers — when he was just 16.

“It was kind of exciting. I just took it as normal.”

For a time it was.

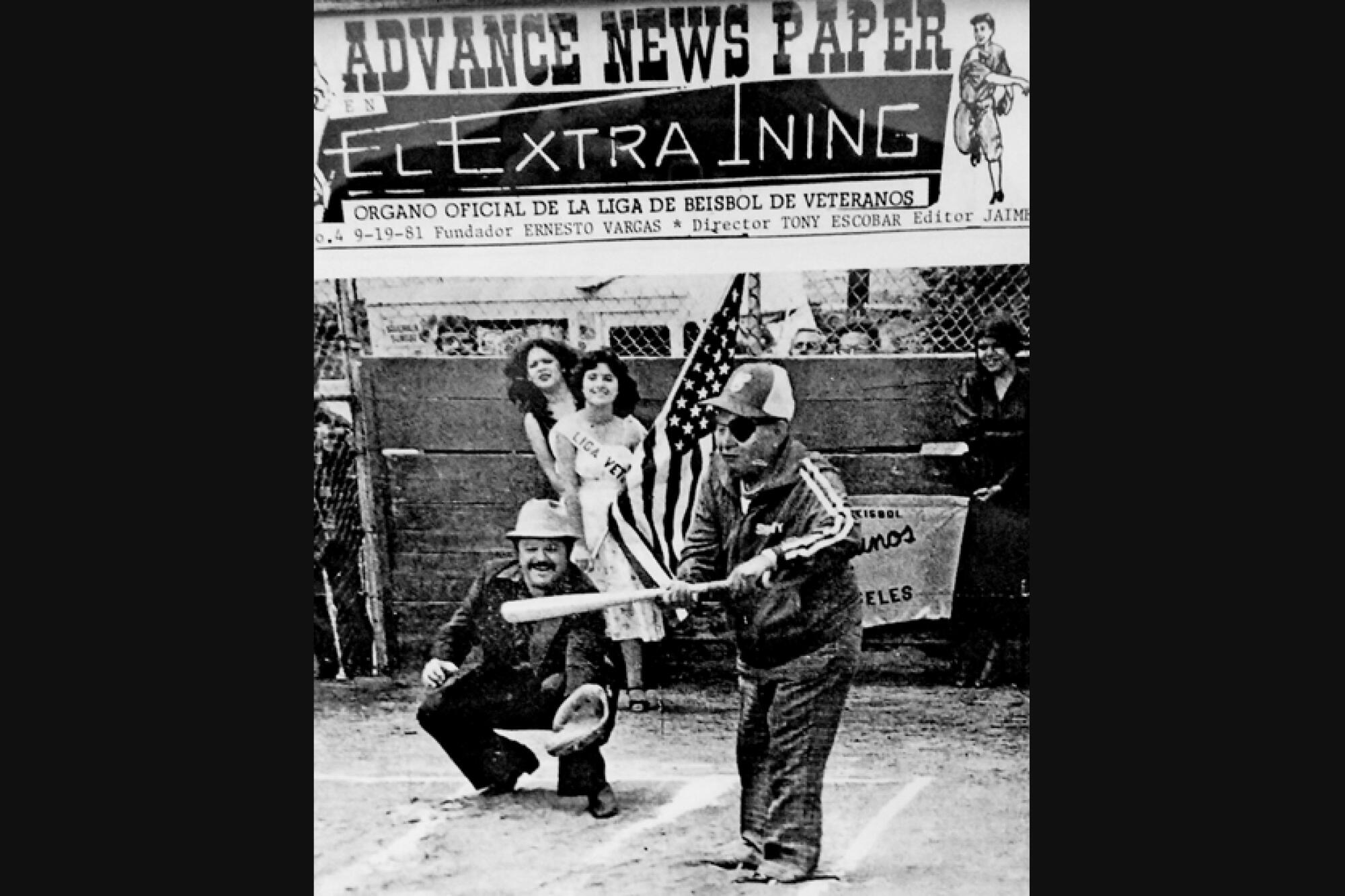

In the years after World War II, a loose affiliation of amateur and semiprofessional teams played nearly every weekend throughout Southern California and northern Mexico. Nowhere were those games bigger than in East L.A., which was transitioning from being the second-largest Jewish community west of Chicago to the single-largest concentration of Mexican Americans in the country.

The emerging Latino neighborhoods of East L.A. and Boyle Heights, made up of native-born Chicanos and Mexican-born immigrants, were split by language and culture and needed something to unify them. That was baseball.

“You’d get standing room only when Carmelita was playing,” Munatones said of the Chorizeros, the New York Yankees of Mexican American baseball with 19 city championships in three decades. “They were just something else.”

Sponsored by the Carmelita Provision Co., the Chorizeros not only had the best players, best manager and best owner, the team also had the best logo — a cartoon pig wearing a baseball hat and taking a healthy left-handed swing with an oversized bat.

A likeness of the pig, visible from what is now the 710 Freeway, once stood guard outside the building on the corner of Floral Avenue and Ford Boulevard. The pig is gone now and the building is a drab, derelict shell — a memory, just like the great teams that used to wear the company’s uniform.

Mario Lopez, the man who ran both the company and the baseball team, had played baseball growing up in Mexico and brought his love for the game with him when he emigrated to the U.S. shortly after World War I. At first he ran a gas station, but after being frustrated trying to find traditional Mexican food in L.A., he closed that, bought a market on Carmelita Avenue and began selling delicacies such as pig’s feet, chicharrones and pork sausage.

Baseball was his real focus, though, and his teams also had the best uniforms, with “Chorizeros” sewn in large cursive script across the front. His largess didn’t stop with the uniforms. Lopez would give away packages of chorizo at games, then invite everyone to a restaurant to celebrate his team’s wins. (One frequent stop was the Silver Dollar on Whittier Boulevard, the restaurant where journalist Ruben Salazar was killed by a sheriff’s deputy while covering the Chicano Moratorium in 1970.)

The rosters were made up largely of teenagers who played at local high schools and players in their mid-30s whose minor league careers had ended. When Munatones was in college at UCLA, he would occasionally come back and suit up on Sundays, even though it could have cost him his college eligibility.

Lopez was also known to hire ringers to work in his sausage factory, looking the other way if they only showed up to play ball on Sundays.

“That was my life. We never missed a Sunday of baseball,” said Art Velarde, who played eight years as a catcher for Carmelita in the 1950s and ’60s. “We were looked up to then.”

Carmelita’s games also became a place for political activity, with voter registration campaigns and citizenship drives taking place behind the backstop and activists sometimes combing the stands for donations to fund discrimination lawsuits. The players, many of whom attended Roosevelt High School in Boyle Heights, supported civil rights and labor organizations.

“Smart politicians attended the games, because that was where the Mexican people were — at the church and ballpark,” Johnny Peña, who played for Carmelita, told an interviewer.

Added Rodriguez, whose brother pitched for a rival East L.A. team before signing with the Baltimore Orioles: “We were sharing something there in the community. It was very nice.”

Years later, as a coach and teacher at Roosevelt, Rodriguez, 83, watched approvingly as students walked off campus to protest unequal conditions in L.A. high schools. The Chicano Blowouts, as the 1968 demonstrations became known, were the largest Mexican American civil rights protests in U.S. history.

The influence on Mexican American baseball history has inspired a series of books, spearheaded by author Richard A. Santillan, with the help of Munatones and other former ballplayers throughout California and the Southwest. The next volume, “Mexican American Baseball in Boyle Heights,” will appear next spring.

::

“It was everything. It was ‘go to church, go play ball.’ That’s what I got a sense of from the guys.”

— Maureen Poon Fear, whose late father played for Carmelita in the postwar years.

The Chorizeros were at their best between the late 1940s and early 1960s, at one time fielding nine brothers from the Peña family. Munatones said he grew up watching the team play.

“My mother, with her wisdom, picked a house a half a block away from the playground,” said Munatones, who went on to play professionally for five years in the U.S. and Mexico, but never played in the major leagues. “I used to hang out in the back end of the batter’s box area. I had my fingers right in the net, my nose to the net, watching the guys play.”

At Evergreen Park, with its short left-field porch, a ball hit over the wall was a ground-rule double. A batter had to clear the chain-link fence surrounding the community swimming pool for a home run.

Not that that was a good thing. Each team brought just one ball to the game, so losing one into the water could prove disastrous.

Rodriguez, a teammate of Munatones at Roosevelt and UCLA who went on to play, manage and scout for the Dodgers, Angels and Giants, also watched those games as a kid.

“That was the closest we were to baseball since Major League Baseball hadn’t come to the Los Angeles area,” he said. “There were a lot of good ballplayers. It was good for the little kids and for the community to see these guys play.”

They had an influence on Maureen Poon Fear’s life as well, although she didn’t know it until years later.

Fear’s father, Wally Poon, played for Carmelita in the postwar years but had given up baseball by the time his daughter was born. He died 40 years ago, at the age of 52, without ever talking to her about those days. But Fear stumbled across his history looking through some old photos, including one the Peñas signed to her father, whom the family looked upon as an uncle.

Fear finally met her “cousins” nine years ago when a plaque honoring Manuel “Shorty” Perez — the Chorizeros’ manager for 34 years, who was buried in his uniform — was unveiled at Belvedere Park.

“It was the most amazing experience I’ve had,” she said. “It’s like they gave [my dad] to me.”

Poon, whose family was Chinese, had grown up in East L.A. and preferred burritos to noodles, his daughter remembered. She also knew he had once owned a sporting goods store and managed bowling alleys. What she didn’t know was that as a young man he starred for the Eastside Merchants and the Chorizeros.

“It was everything. It was ‘go to church, go play ball.’ That’s what I got a sense of from the guys,” Fear said. “They didn’t need the Dodgers. Everything was there, the community, the teams. They were such celebrities.”

Velarde told Fear her father had given him his first bat. An aging Richie Peña said Poon had given him his first baseball glove.

“I realized that he died really young but, man, he had a great life and he had the best friends,” Fear said. “They love him so much, even now. So that’s my connection with the whole East L.A. thing.”

::

“Barrio baseball, in its time, routinely brought three generations together on a weekly basis and was a valued tradition now lost to history.”

— Samuel O. Regalado, Cal State Stanislaus history professor

Wally Poon had stopped playing baseball and had started a family by the time the Dodgers started construction on a stadium in Chavez Ravine, which is a whole other chapter in the Mexican American baseball story in Los Angeles.

Munatones was in his final minor league season when the Dodgers played their first game there. Amateur and semipro baseball across the river in East L.A. wasn’t dead yet; in fact, it would go for another decade.

But it would never be the same.

“We were still big. But most of the interest went because, you know, Vin Scully [was] on the radio. Fans would take the streetcar or the bus or whatever to get to Dodger Stadium,” said Rodriguez, who had also moved on by then. “That became big baseball.”

The Dodgers aren’t solely responsible for chasing barrio baseball away. Regalado, the Cal State Stanislaus history professor, says freeway access caused much of the talent in East L.A. to begin moving out of the barrio in the 1960s and ‘70s. Some teams, such as the Los Angeles 40-60 club, weren’t tethered to the old neighborhoods like business-sponsored teams and were also free to move.

“Barrio baseball, in its time, routinely brought three generations together on a weekly basis and was a valued tradition now lost to history,” Regalado said.

The games — like the players and the teams — have been gone for decades now.

So as the lights at Dodger Stadium, clearly visible from East L.A., come back on this week, Rodriguez, who once chased those lights as a young player in the Dodgers’ minor league system, says he’ll still be pining for the days when baseball in Los Angeles didn’t mean the Dodgers and Giants at Dodger Stadium.

It was the Chorizeros and Eastside Beer at Evergreen Park.

Watch LA Times Today at 7 PM on Spectrum News 1 on channel 1, on Cox systems in Palos Verdes and Orange County on channel 99, and live stream on the Spectrum News App.