Criticism grows over Gov. Gavin Newsom’s management of the coronavirus crisis

SACRAMENTO — Advocates for seniors and people with disabilities blasted Gov. Gavin Newsom’s administration last week for advising hospitals to prioritize younger people with greater life expectancy for care during the coronavirus outbreak, saying the state’s medical shortage guidelines were discriminatory and crafted without their input.

“The disability, aging and older-adults community had reached out a number of times to the state of California sharing our concerns ahead of time and offering to meet,” said Claudia Center, legal director for the Disability Rights Education & Defense Fund. “We got no response.”

Then, as quietly as the guidelines were initially posted online, the document was removed and replaced with another version stating California’s commitment to prohibiting discrimination and promising that the administration would revise what had been previously labeled as the final recommendations “to ensure that they reflect our values as a state.”

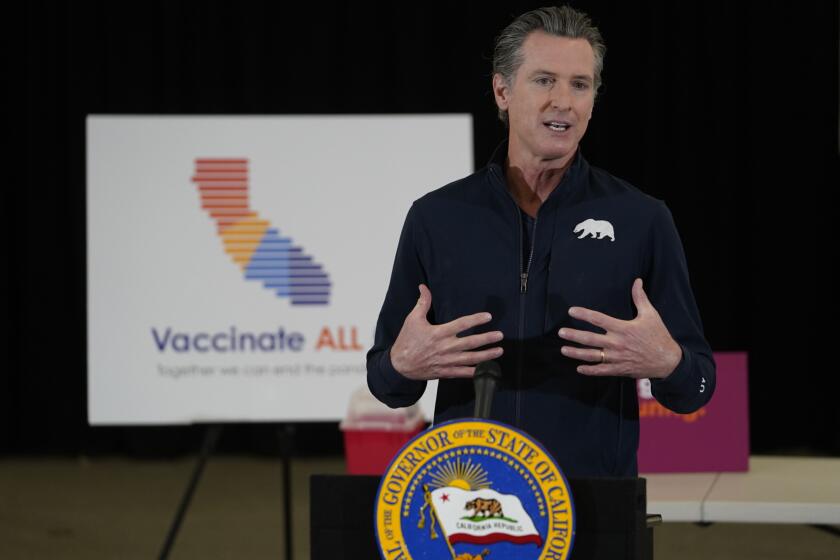

Initially applauded for his approach early in the coronavirus crisis, Newsom was the first governor to impose a statewide stay-at-home order, a move that health experts have credited with slowing the spread of the coronavirus and helping California record far fewer deaths than hot spots such as New York. He’s also become a fixture on cable TV, touting how California bent the curve. But Newsom’s recent waffling on the life-and-death decision and other actions have renewed critiques of the impatient, and at times chaotic, governing style that dogged Newsom in his first year in office.

Though state lawmakers and advocates for businesses, nonprofits, seniors, healthcare and other groups waited their turn for aid or hesitated to speak out during the first few weeks of the unprecedented crisis as the governor grappled with immediate needs to slow the spread of the virus, that patience is running out. Legislators and advocacy groups want more input, while others criticize the governor’s decisions or say he needs to do more to help their communities.

“We’re just not getting answers to what we need, but I also think that we’re seeing some missteps,” said Jan Masaoka, chief executive of the California Assn. of Nonprofits.

Nathan Click, a spokesman for Newsom, defended the governor for keeping Californians safe in a pandemic.

“Gov. Newsom has moved swiftly to protect human life, and he has taken aggressive and urgent actions to help Californians get through these challenging times,” Click said. “Because of those efforts and the actions of millions of Californians who are staying home, California has both flattened the curve and helped millions of its most vulnerable residents as they tackle the unprecedented challenges of this crisis.”

Newsom took office with flush cash reserves and the wind at his back, allowing him to work with the Democratic Legislature to cap rent increases for the first time, expand Medi-Cal to young immigrants living in California without legal status, expand preschool and make strides on other progressive causes.

The outbreak has quickly thwarted any hopes that a rosy economy would continue to buoy his first term. Now the list of problems for the Democratic governor to solve is growing by the day as a record number of Californians seek unemployment benefits, revenue is sliding and officials peg an at least $7-billion price tag on state efforts to fight the virus through June, a projection that will grow should the state remain in the throes of the pandemic into the fall.

“With a situation like this, there’s so many crosswinds. He’s got people begging him to reopen. He’s got other people begging him to do things on the health front, on the economic front,” said Steve Maviglio, a Democratic strategist and former press secretary for Gov. Gray Davis. “There’s so many constituencies that it’s really difficult to keep all of them happy.”

As the economy plunges, companies are looking to Newsom — who has often reminded the public of his small-business background — to allow businesses to operate normally again and help them get back on their feet. But the governor angered many in the business community when his administration floated potential changes to workers’ compensation that could allow employees to qualify for financial support even if they didn’t contract COVID-19 on the job, a shift estimated to cost up to $33.6 billion annually.

Meanwhile, several local officials across California are demanding that Newsom ease his stay-at-home order — or at least provide more details on his plan to return to normalcy.

When Newsom announced a 100-member task force of business executives, heads of labor unions and former government leaders tapped to develop a plan to jump-start the economy, some questioned what it might accomplish. The group of power players, led by former presidential candidate and major Democratic donor Tom Steyer, is meeting twice a month, which some say isn’t frequently enough to devise strategies to provide immediate help to struggling companies and workers.

“We’re coming to a point where people’s fear for feeding their families supersedes the fear of the virus,” said Rob Lapsley, president of the California Business Roundtable. “He’s working hard and his actions have unquestionably protected the public health. But we have to have a more urgent discussion about the economy.”

Lapsley said the governor has not responded to multiple coalition letters highlighting problems that businesses anticipate as they attempt to recover.

In addition, lawmakers are upset over a lack of transparency from the governor and his refusal to release details on a nearly $1-billion deal to buy masks from Chinese electric automaker BYD. Others have lamented Newsom’s frequent use of his executive authority since the Legislature left the state Capitol last month.

“The problem that my members have is the lack of lead time,” Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon (D-Lakewood) said of Newsom’s executive action announcements. “They feel like they are being told just before the public is told, but without enough time to provide any meaningful feedback.”

When asked about the secrecy around the contract, Newsom brushed off the concerns and repeated a familiar defense: He should be judged by outcomes, not the means to those ends.

“Some are consumed by process, personality, intrigue, who’s up, who’s down?” the governor said. “We are for actually solving a major, major problem.”

Newsom has revealed new policy initiatives at almost all of his daily news conferences, keeping a quick pace that has led to premature introductions of some of his plans.

The governor declared on April 22 that surgeries in California would resume, a move largely perceived as the first sign of a return to normalcy in the state, where nearly 40 million people have been ordered to remain at home for more than a month.

“We are in a position today to begin to pull back and lean in by beginning to schedule surgeries, once again, throughout not only our hospital system, but our broader healthcare delivery system,” Newsom said, noting that efforts to flatten the curve enabled the state to “move more formally with our partners at a local level and throughout the healthcare delivery system to once again schedule surgeries.”

But at the time of his announcement and for several days after, the state had not set any guidelines or policies advising hospitals to resume services. In response to a request the day after the announcement for details on which services would resume and which procedures had been previously allowed, California Health and Human Services spokeswoman Kate Folmar said state officials were talking to “a stakeholder work-group and will be producing more specific guidance on this.”

California Hospital Assn. President Carmela Coyle said in a email to some in her group that the administration wasn’t moving to immediately restart surgeries, and she acknowledged frustrations among hospitals over Newsom’s “mixed message.”

On Monday, the state released formal guidelines that described which services should be prioritized and resumed “as soon as practicable,” and the preparations hospitals should make before doing so.

“These guidelines were developed rapidly following the governor’s announcement last week that hospitals would be restarting many health care services,” Coyle said in another email to members after the guidelines were released.

Days after announcing that surgeries would resume, Newsom boasted that 26,000 Californians had heeded a call he issued for volunteers to work at food banks, make phone calls to seniors and provide help to nonprofits under a new service initiative called “Californians For All” led by the state’s Chief Service Officer Josh Fryday and the governor’s wife, First Partner Jennifer Siebel Newsom.

“I just want to thank all of those that have done so and extend a heartfelt expression of appreciation to help others,” Newsom said on Friday.

But Masaoka of CalNonprofits said her association suggested a better way to roll out the initiative and the advice was ignored.

“The fact is that we in the nonprofit community know how to recruit volunteers, so why not ask us? Why not use the mechanisms that are in place to already do that?” said Masaoka of CalNonprofits. “They were in a hurry to do something, and it doesn’t seem that they gave it the thought that a project like that needs.”

CalVolunteers approached her organization, which represents nearly 10,000 charitable groups in California, and asked if they would team up on the campaign, she said. The association agreed to help and suggested the administration also work with VolunteerMatch, an Oakland organization that many of California’s nonprofits use to recruit volunteers by posting detailed listings for the roles that they need to fill, Masaoka said.

“They didn’t get back to either one of us, and days later they announced it,” Masaoka said. “Our feeling is that yes, not all nonprofits need volunteers, but many nonprofits do need volunteers, but giving names and emails in an undifferentiated way ...isn’t the way to do it.”

A week after introducing the initiative, the state changed course and is now working with VolunteerMatch.

At the same time, Masaoka said the administration hasn’t helped nonprofits with more pressing concerns.

CalNonprofits has asked Newsom to direct state agencies and contractors to continue to pay nonprofits even if the COVID-19 crisis prevents them from reaching certain benchmarks in their contracts for government funds. The restrictions, for example, may prevent childcare facilities from serving as many children as usual, or healthcare clinics from providing a set number of tests given that regular care is limited. Without such assurances, which San Francisco and the federal government have addressed, she said, nonprofits could have to shut their doors.

More than 1,000 nonprofits signed a letter to Newsom and legislative leaders on March 21 asking for help, and 30 Assembly members followed with their own letter on March 31.

“Nonprofits are actually on the front line during the pandemic and we seem to be at the back of the line in terms of any policy support in Sacramento,” Masaoka said.

Newsom also frustrated some nurse practitioners after he touted an executive order at a March 30 press conference that he said would help the state “utilize our existing resources in a more resourceful way” through scope of practice reforms.

The announcement drew immediate attention to a long-simmering debate in the Legislature, where nurse practitioners have for years battled with the powerful physicians’ lobby for changes that would allow them to work without a doctor’s supervision.

“I want to thank all representatives for putting aside, again, those differences and meeting this moment head-on to provide the flexibility that is required,” Newsom said. “An executive order that went out ... will provide flexibility through June 30. This is temporary flexibility on staffing ratios, on scope of practice for nurse practitioners, EMTs and others.”

But it was unclear precisely what the order would do, and it did not take effect immediately. The order ultimately allowed the Department of Consumer Affairs and licensing boards to lead decision-making on scope of practice. Two weeks later, action was taken to increase the number of nurse practitioners a doctor can oversee — without the scope of practice changes advocates had expected.

Center, the legal director of the Disability Rights Education & Defense Fund, said she is awaiting new guidelines and appreciates that the state is now accepting input from advocacy groups, but she noted that the early directives on rationing care won’t be easily forgotten.

The 38-page document by the California Department of Public Health, which is now being revised, prescribed a method to prioritize patients if an outbreak overwhelms hospitals, preserving intensive care beds and ventilators for people with the greatest likelihood of surviving with treatment over those with serious chronic conditions that limit their life expectancy. If necessary, younger people and workers who are “vital to the acute care response” would receive care before others, the document said.

“It, as a document, communicates what the medical establishment and state government think about disabled people and older adults,” Center said. “We know what this means, and we remember, and it’s hurtful.”

Staff writers Melody Gutierrez and John Myers contributed to this report.