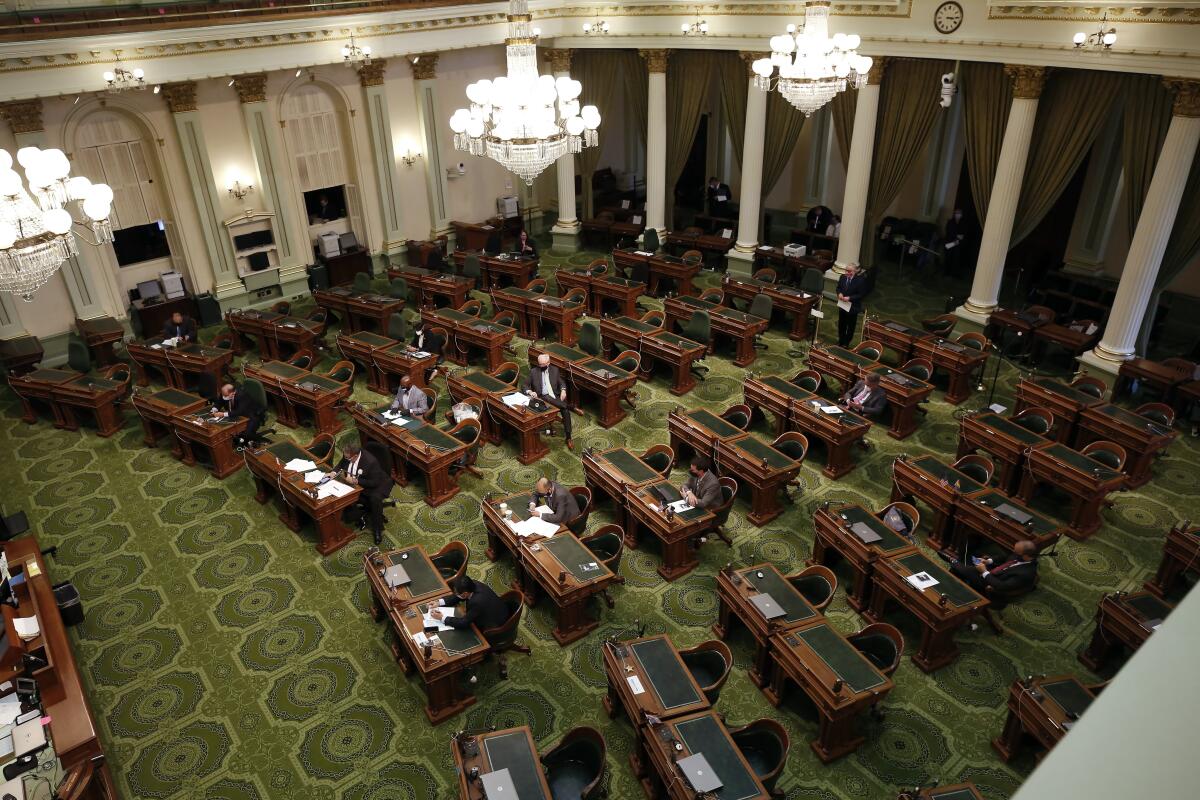

California Politics: What’s driving a historic exodus from the California Legislature?

Chad Mayes has had several important titles over the course of more than two decades in politics: city councilman, mayor, Assembly member, Republican leader, independent legislator.

But by the end of the year, his designation is likely to be ex-politician. And if so, it will be entirely by choice.

“I’m not the only one that’s thinking this way,” Mayes said. “And the question becomes, who’s going to be left to fill the void?”

With one month remaining to file the paperwork for the 2022 elections, it has become impossible to ignore the historic exodus of incumbent members of the California Legislature.

While there have been other eras of great turnover in the state Senate and Assembly, the change now underway is being led by lawmakers who are voluntarily stepping down — with a surprising number of them choosing to do so in the middle of their current term.

For some, it marks not only the end of their time in Sacramento but the realization that their idealism was no match for the one-two punch of powerful interest groups and the era’s angry, uncompromising political climate.

‘We actually failed miserably at that’

Mayes, an affable legislator from Yucca Valley, has had more ups and downs than most of his Assembly colleagues.

Elected as a Republican in 2014 after serving in local government, he quickly found himself on an escalator to real power in Sacramento — chosen as Assembly Republican leader a little more than a year after arriving in the Legislature. But his work on a bipartisan agreement on climate change policy in 2017 led to his ouster from the leadership post. After briefly trying to forge a different path in Republican politics, Mayes left the party and won his current term as an independent.

But party politics is only part of the story he tells in why he decided not to seek another two-year term.

“I thought we could change the system,” Mayes said in looking back at the expectations of lawmakers elected after voters loosened California’s legislative term limits in 2012. “There was this sense that we were going to take [power] back from the lobbyists, we were going to take it back from the staff.”

Seven years later, Mayes offers a concession.

“We actually failed miserably at that,” he said.

In part, that view is colored by the inherent tension between governing and campaigning. Other issues also come up in conversations with current and former lawmakers about what’s changed. The COVID-19 pandemic has stymied many of their policy objectives while raising health concerns for legislators and their families. The bitter polarization has left little, if any, room to negotiate.

And for some members of the Legislature elected in 2012 and 2014, last year’s redrawing of political maps has left them facing the prospect of a grueling campaign to win over brand-new voters — to then have only two years before term limits send them looking for another job.

“The political world right now is brutal,” said Ian Calderon, the former Assembly majority leader who opted not to run again in 2020. “It takes a massive toll on your life.”

(At least) 35 lawmakers won’t be back in 2023

The number of sitting legislators who are stepping aside grew on Thursday, when Assemblymember Jim Cooper (D-Elk Grove) announced he will run for Sacramento County sheriff.

More than one in four members of the Legislature who took the oath of office in December 2020 will be gone when the new legislative session begins after this year’s elections. At least 25 members of the 80-member Assembly will have departed, along with 10 men and women in the 40-member Senate.

While the Senate turnover will largely be consistent with previous cycles, the exodus is most pronounced in the Assembly. Five of the lower house’s members have already resigned, the latest being former Los Angeles County Assemblymember Autumn Burke, who gave 24 hours notice before her Feb. 1 resignation, saying it was of “the utmost importance that I have the flexibility and ability to spend more time with my family.”

Fourteen more have announced they’ll retire at year’s end. Five more will lose to a fellow incumbent on election day, drawn into the same district as their colleague under last fall’s statewide redistricting — assuming, of course, they don’t change their mind and drop out.

But it’s the high number of voluntary departures that provides the real eye-opener. In 2012, California’s last post-redistricting cycle, only four Assembly members made the same choice. That year, more than half of the lower house’s vacancies were due to term limits.

Others might follow

“I believe public service is a high calling,” said Mayes, who admitted to being a little bleary-eyed during an interview with The Times, his schedule now split between working for his constituents and tending to his 6-week-old daughter.

But the Mojave Desert lawmaker also said he’s had private conversations with colleagues from both parties who are, in his words, “trying to hold on for dear life” in grappling with the challenges of a job they feel is harder than ever before.

Calderon, a father of four young children who struggled with the logistical and financial challenges of elected office, said it’s clear a number of legislators have come to the same realization that he did — something’s got to give, especially in these polarized times.

“That is a very difficult decision to make,” he said. “And I don’t think people don’t really grasp how difficult that can be.”

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

In search of GOP voters

Lost in much of the week’s politics news was another sobering statistic about California’s second-largest political party that made clear it’s still getting smaller.

A report issued Thursday by Secretary of State Shirley Weber showed that the number of California voters — slightly more than 22 million — is pretty much unchanged from just before the gubernatorial recall last September.

But Republican Party registration in the intervening months has dropped as the number of Democrats has risen. The new report shows almost 28,000 fewer GOP voters in California than right before the recall election, while there are now about 9,400 more Democrats. It’s possible some of the ex-GOP voters joined the far-right American Independent Party or the Libertarian Party, which both saw a slight uptick in membership.

Stepping back to view the registration numbers in comparison to those from 2006 — the last time a Republican won a statewide office — offers a pretty simple reason for why Gov. Gavin Newsom’s reelection chances are awfully good. There are now almost 212,000 fewer GOP voters in California than when then-Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger was seeking a second term. But there are some 3.5 million more Democrats than in 2006. The registration gap is now more than 12 percentage points, a sobering reality for Republican state Sen. Brian Dahle, who announced this week that he’ll run against Newsom.

Sign up: L.A. On The Record

It’s shaping up to be a huge election year in Los Angeles and our local politics team will have it covered in a new weekly newsletter.

No race is bigger than the wide-open contest for mayor, but there are a number of other high-profile city and county races too. Beginning next week, our City Hall and local politics reporters will make sense of it every Saturday in “L.A. On The Record,” a newsletter that will keep you plugged in as election day approaches.

Sign up on our newsletters page.

California politics lightning round

— Alarmed by a major oil spill off the Huntington Beach coast in October, an Orange County legislator has introduced a bill to end offshore oil production from rigs in California-controlled waters by 2024.

— Lawmakers passed legislation this week, quickly signed by Newsom, to provide most Californians with up to two weeks of COVID-19 supplemental paid sick leave. Here’s how it will work.

— Among the many changes proposed to California’s “three strikes” law, one of the most narrow would be to limit its use in juvenile cases. But that effort has stalled in the Legislature.

— As California grapples with a massive shortage of behavioral healthcare workers, state lawmakers want to offer financial incentives in hopes of bringing in and retaining more professionals to improve access to mental health services.

— Can you conserve water and increase California’s energy supply at the same time? George Skelton’s idea: “Plow over some San Joaquin Valley croplands and plant solar panels. Turn alfalfa fields and nut orchards into solar farms.”

Stay in touch

Did someone forward you this? Sign up here to get California Politics in your inbox.

Until next time, send your comments, suggestions and news tips to politics@latimes.com.