Column: California’s ballot measures will produce a deluge of special-interest cash

You can lay the hand-wringing about the failing condition of the American economy aside for a moment, because one sector is blazingly fat and likely to become even more so between now and election day.

We’re talking about spending on California ballot measure campaigns.

Twelve measures will be on the state’s November ballot. Some of them concern issues unrelated to any particular business’ pocketbook. Those include measures devoted to voting rights (two measures would expand the franchise to parolees and 17-year-olds), affirmative action (repealing a 1996 Republican-sponsored measure that ended it in California), and a tough-on-crime stance that would reclassify some misdemeanor drug and property crimes as felonies.

But others will either make certain businesses more profitable or reduce or eliminate regulations on them. That’s where the monetary rubber meets the road.

The initiative, the referendum, and the recall...place in the hands of the people the means by which they may protect themselves.

— Gov. Hiram Johnson, 1911

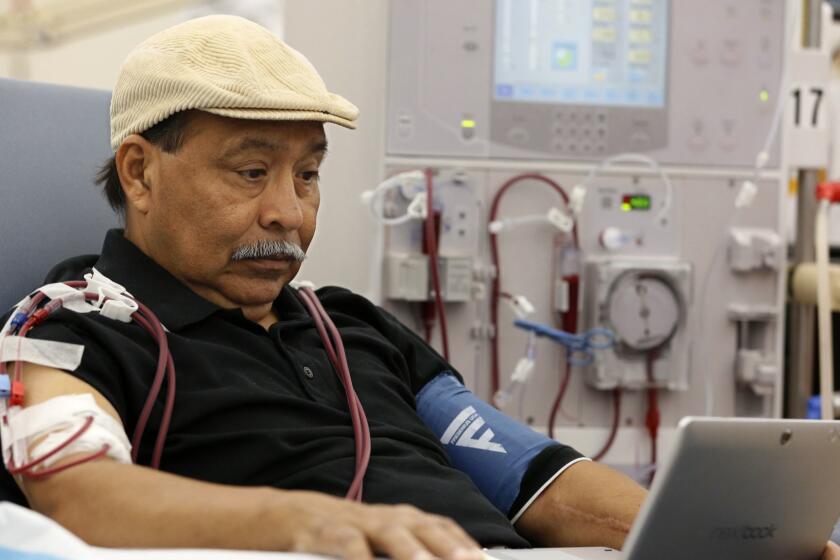

The big players thus far this year are the ride-hailing companies Uber and Lyft and the dialysis companies DaVita and Fresenius.

Proposals to raise property taxes on commercial real estate, to expand rent control laws and to renew the state’s stem cell program have already attracted millions of dollars and are likely to fill ever-bigger moneybags in the next three months.

Thus far, contributions for and against the big-money initiatives are totaling more than $185 million.

Almost certainly that’s an undercount, for some donations are hard to track. Initiative campaigns are conducted by political action committees and other entities whose role may not become clear until closer to the election.

Some have been collecting from donors for several years as their initiatives make their way through the legal qualification process, and those donations aren’t always applied reliably to current disclosures. So the figures at hand are provisional, at best.

It’s fair to predict, however, that spending on at least one or two of the dozen 2020 ballot measures could challenge the previous record of $172.7 million spent in 2008 on four California ballot propositions aimed at expanding Indian gaming in the state. Almost two-thirds of that money was spent in favor of the initiatives, which passed.

Uber and Lyft are being squeezed by enforcement of California’s gig worker law.

The runner-up in spending was Proposition 87 of 2006, which would have imposed a state severance tax on oil and gas extracted from California lands and attracted more than $150 million in spending pro and con. Of that, the petroleum industry spent more than $94 million, almost all of it contributed by petroleum companies, and killed the measure.

In third place was the battle over Proposition 8 in 2018, which would have placed limits on dialysis revenues. DaVita, Fresenius and a third dialysis firm managed to kill the measure by spending some $111 million against it. The Service Employees International Union, which has been trying to unionize the companies, mustered a mere $19 million and lost.

Two other battles over measures aimed at reducing drug prices, in 2016 and 2005, filled out the top-five list on spending.

The California campaigns, incidentally, also established nationwide records. That partially reflects the state’s size and the consequent necessity of conducting political campaigns through expensive advertising.

But it also underscores a dirty reality of California politics, which is that business and industry often finds it more expedient to get what they want by resorting to the ballot box rather than the toilsome and less-rewarding effort of lobbying the Legislature.

The initiative process established by Gov. Hiram Johnson in 1911 has thus been perverted beyond recognition.

Johnson was a combative progressive Republican — he ran for vice president on Theodore Roosevelt’s Progressive, or “Bull Moose,” ticket in 1912 — who aimed to undermine the political influence exercised in California by the Southern Pacific Railroad, which was known as “the Octopus.”

Johnson told the Legislature that “the initiative, the referendum, and the recall ... place in the hands of the people the means by which they may protect themselves.” Times have changed.

Big companies don’t normally invest tens of millions of dollars with the expectation of losing.

To see how Johnson’s innovation may play out in November, let’s look briefly at some of the key proposals.

—Uber, Lyft, et al: The ride-hailing companies have joined with gig companies DoorDash, Postmates and Instacart in funding Proposition 22 with $111 million (as of March 31). Their goal is to overturn AB 5, the state law that would require them to designate their drivers as employees rather than “independent contractors.”

The change would require them to provide drivers with a host of workplace protections, including a guarantee of minimum wages and overtime, company-paid expenses such as fuel, insurance and wear-and-tear on their vehicles and the right to form a union. The measure would not only effectively designate app-based drivers permanently as independent contractors, but forbid the state or localities to enact ordinances to treat them as employees.

The companies’ spending on Proposition 22 thus far has swamped that of the measure’s opponents, who have disclosed only about $700,000 in contributions, mostly from organized labor.

—The dialysis industry: DaVita and Fresenius on the one hand and the SEIU on the other are replaying their 2018 ballot-box battle with Proposition 23. The measure doesn’t go nearly as far as the 2018 version; it merely sets minimum standards for physician staffing at dialysis clinics and requires expanded disclosures to state health authorities.

As a result, the measure hasn’t yet generated the spending that the previous initiative did. DaVita and Fresenius have each contributed about $1 million as of May, with SEIU ponying up about $6 million. It’s doubtful this campaign will have the financial heft of its predecessor, but if SEIU wins this time, it may be emboldened to return to the ballot box in the future with more stringent measures.

DaVita and Fresenius collect billions of dollars in fees for dialysis every year, and their determination to protect that revenue with aggressive defenses at the ballot box has been proven.

—Bail bonds: As we’ve reported, the cash bail system is a big, global business that masquerades behind a facade of mom-and-pop storefronts. The real powers behind the industry are international insurance companies for whom a system of charging exorbitant fees to families who can barely afford them has been worth billions a year.

The bail industry will spend lavishly to pass a self-interested ballot measure in 2020. Don’t bite.

Insurers have contributed the lion’s share of the roughly $3.9 million collected to defeat Proposition 25, which would allow a 2018 law banning cash bail for criminal defendants to finally go into effect. That would effectively eradicate the bail industry in California, which would be a good thing. Supporters of the measure, mostly activist groups, have raised about $1.3 million.

Cash bail exacerbates racial and socioeconomic inequities already present in the criminal justice system by tying pretrial detention to a defendant’s ability to pay bail: Wealthy defendants are set free to work on their defense, while less-affluent defendants have to cool their heels behind bars.

The 2018 law signed by Gov. Jerry Brown would give judges far more latitude to decide whether to hold defendants before trial by making considered judgments on the likelihood they’ll show up.

The vast majority of defendants, whether out on bail or released on their own recognizance, show up for court dates. Nor do they go on crime sprees once they’re out on the street. But the law has been held in abeyance by the bail industry’s success in placing Proposition 25 on the ballot.

—The split roll and rent control: Real estate being California’s official state obsession, two ballot measures devoted to the issue have the potential to be financial barn-burners.

Proposition 15 would create a so-called split roll requiring commercial properties to be regularly reassessed. This perennial idea is a way around Proposition 13, the property-tax limitation that was enacted in 1978 purportedly as a protection for residential homeowners, but which has turned out to be a boon for commercial property owners.

Advocates of the split roll have noted that Proposition 13 has allowed some commercial properties — Disneyland, for example — to still be taxed at 1970s valuations. Changing that system could produce as much as an additional $12 billion in tax revenues in its initial years, according to a 2018 estimate by a team from USC.

So far the supporters of Proposition 15, including teacher unions, have raised more than $14 million, according to Ballotpedia, which says business interests have contributed about $3 million. But the battle is in its early stages.

The initiative has attracted a relatively new participant in California electoral politics—the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, which is funded by Facebook Chair Mark Zuckerberg and his wife, Priscilla Chan. The Initiative announced Friday that it will add $4.5 million to the $1.8 million it has already contributed to the Proposition 15 campaign. (The Initiative is also contributing $1.25 million to the effort to defeat Proposition 20, the so-called tough-on-crime measure.)

Proposition 21 would modify the Costa-Hawkins Rental Housing Act, a pro-landlord measure signed by Republican Gov. Pete Wilson in 1995 that has hamstrung local authorities from expanding rent control for certain properties ever since.

Could a reassessment of Proposition 13 finally be in the wings?

When the issue last appeared on the ballot in 2018, apartment developers and other real estate interests raised more than $70 million to defeat it. The initiative’s sponsor, the AIDS Healthcare Foundation, headed by persistent government gadfly Michael Weinstein, countered with more than $25 million in a losing battle.

They’ll be facing off again. So far, the “Yes” camp has raised more than $15 million, mostly from Weinstein’s foundation. Real estate interests have raised more than $6 million, a figure destined to grow.

What’s demoralizing about the inflow of millions of dollars into these campaigns isn’t simply the scale of the resources, but the uses to which the money is put. Advertising for ballot measures is an especially malodorous corner of political speech, often tendentious and deceptive.

It’s true that in campaign season everyone is addicted to this exploitative process — the promoters and opponents of ballot measures, the campaign consultants who design the campaigns, and the broadcasters and publishers who get paid to run them. But let’s not overlook how the public interest gets buried.

When the proponents or opponents are commercial entities, their true interests are almost invariably cloaked. Nor are proponents of measures that arguably serve the public interest necessarily innocent of shading the truth, because shoehorning the facts about a law or constitutional amendment into the confines of a 30-second spot is a hopeless task.

If any voters have ever learned anything truly useful or pertinent about a ballot measure from a campaign ad, whether on television, radio or online, I’d be fascinated to hear from them. Millions of dollars will be spent on California’s ballot measures this year, and all of it might as well go up in smoke.