The Fed took bold steps to boost the economy. Will undoing one of them rattle markets?

Now, with the economy healthier — and mixed opinions about how much the bond purchases actually helped — the Fed is preparing to scale back its massive stock of about $4.5 trillion in assets.

Those holdings of mostly Treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities are more than quadruple what they were before the crisis, and reducing them is another risky move that could affect mortgage rates, consumer prices, bank lending, stock values and federal government borrowing.

But there’s also risk to standing pat. Like any investor, the central bank could suffer losses on the bonds if it holds them too long and interest rates rise. At the same time, holding a lot of assets could make it harder to buy more if that’s needed to fight a future recession.

So Fed policymakers plan to start trimming their holdings this year. They hope to do it gradually and seamlessly, without the controversy and fanfare that has made the once-boring institution a political target and shaker of financial markets.

“We think this is a workable plan and it will be … like watching paint dry,” Fed Chairwoman

That wasn’t the case in 2013.

Then-Fed Chairman

Fed officials learned from that experience. This time, they have carefully signaled their plans in recent weeks and have promised to proceed cautiously to avoid spooking investors and harming the economic recovery as well as their own credibility.

“They’re trying to make as little impact as possible on the markets,” said Jack Ablin, chief investment officer of BMO Private Bank in Chicago. “By moving in a very incremental fashion and telegraphing their intentions, they hope investors will allow them to execute the program without much turbulence.”

But there’s uncertainty about how the unwinding scheme will play out.

While the bond purchases never set off wildfires of inflation, as many critics warned they would, economists and financial analysts remain divided about how much economic stimulus was provided. And there’s little agreement on how much of the money the Fed created to buy the bonds should be kept in the financial system.

Here’s a look at the bond-buying program and how the Fed will try to unwind it.

A push to lower mortgage rates

The 2008 financial crisis supercharged the recession that began about a year earlier, threatening to plunge the nation into another Great Depression. The Fed already was well underway in lowering its key short-term rate close to zero. But the economy remained in deep trouble.

So Fed officials tried a tactic pioneered by Japan’s central bank in the early 2000s: large-scale asset purchases known as quantitative easing.

The idea is simple, but controversial.

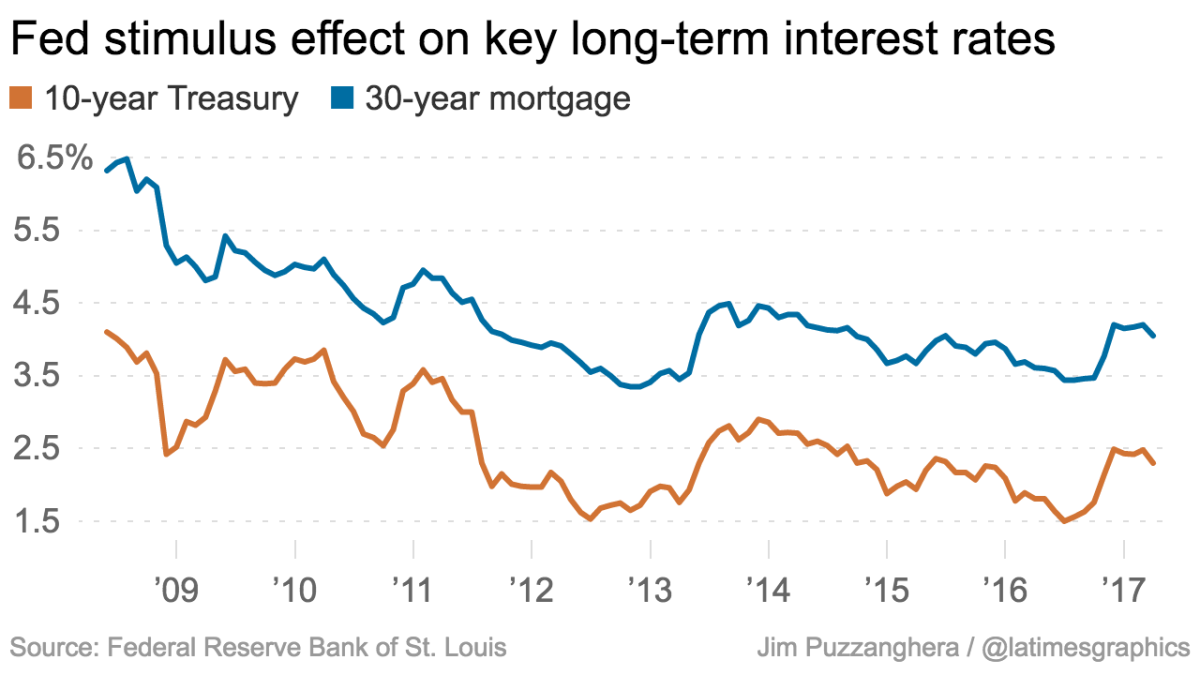

Purchasing government bonds and mortgage-backed securities tends to push down mortgage and other long-term interest rates. Mortgage rates are tied to the value of Treasury bonds, and the higher demand for mortgage-backed securities also helps push rates lower because the return on those securities doesn’t have to be as large to attract investors. Those falling rates encourage spending and investing over saving.

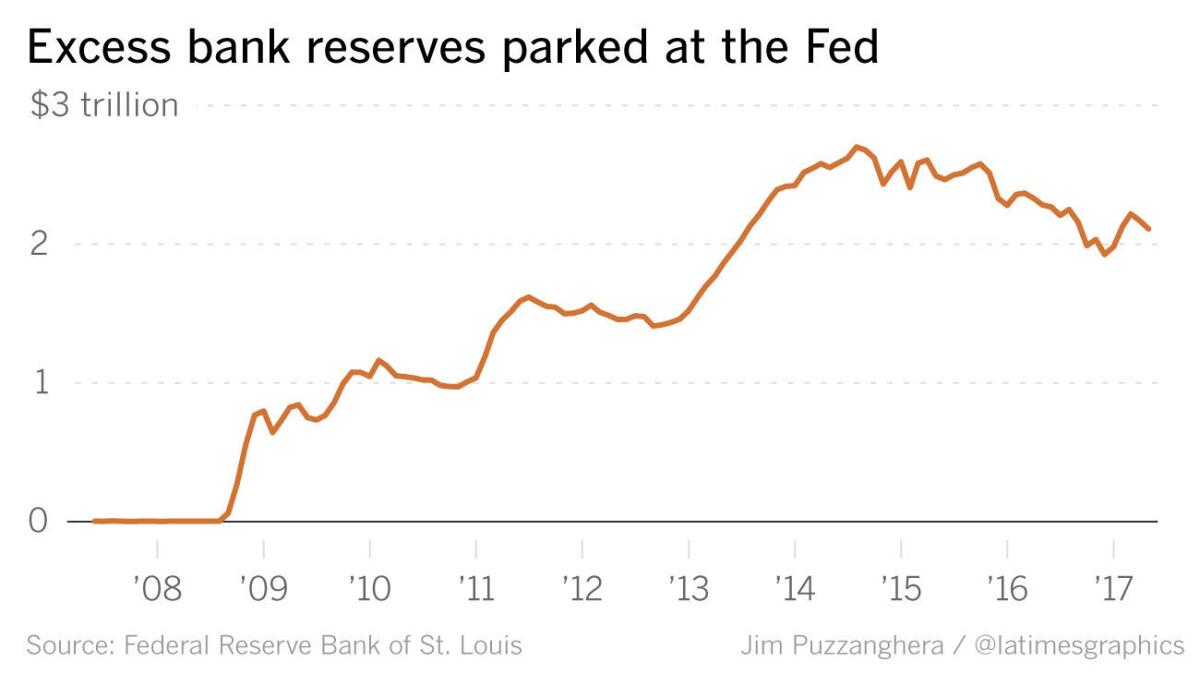

The move also increases the money supply because a central bank buys the bonds by electronically increasing the reserves it holds of the commercial bank from which the purchase was made. So, in effect, the Fed prints new money, which can be borrowed and spent.

Fed policymakers launched three separate rounds of quantitative easing, purchasing Treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities, as the economy continued to recover slowly and unemployment remained high.

Federal Reserve quantitative easing bond purchases

- First round: $1.75 trillion, Nov. 2008-March 2010.

- Second round: $600 billion, Nov. 2010-June 2011.

- Third round: $1.64 trillion, Sept. 2012-Oct. 2014.

The effort “significantly lowered long-term interest rates which helped support the housing market and the broader economy,” said Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Analytics.

“I think it was a very positive step in support of economic growth,” he said.

An analysis by Zandi and Princeton economist Alan Blinder determined that the bond buying increased total U.S. economic output by 1.5 percentage points through the first quarter of 2015. And it provided the stimulus without the high inflation some experts warned would come from adding so much money into the economy.

Other analysts said the Fed’s stimulus plan helped only marginally in stimulating the economy and wasn’t worth the risks. While the unemployment rate declined from 10% in late 2009 to 5.7% when the bond-buying ended five years later, economic growth remained lackluster.

“Normally that kind of asset acquisition would have been expected to lead to a vast increase in spending,” said George Selgin, director of the Center for Monetary and Financial Alternatives at the Cato Institute, a libertarian think tank. “It didn’t stimulate spending very much at all.”

Banks chose to hold onto much of the money they got for selling the bonds, rather than lend it.

Lee Ohanian, an economics professor at UCLA, said most studies have indicated that the Fed’s bond purchases lowered long-term rates between 0.25 and 0.75 percentage points. The rate on the 10-year bond is currently about 2.3%.

Ohanian thinks the effect was modest, on the lower end of that range.

The Fed was not alone in using bond purchases to try to battle the fallout from the Great Recession. Central banks in England, Japan, Switzerland and Europe also launched asset-purchase programs to try to stimulate growth in their economies.

With the Fed and some other major central banks signaling plans to curb their bond purchases and end a long period of stimulus policies, in recent days investors have sold off U.S. Treasury securities and that has sent long-term rates higher.

A ballooning balance sheet

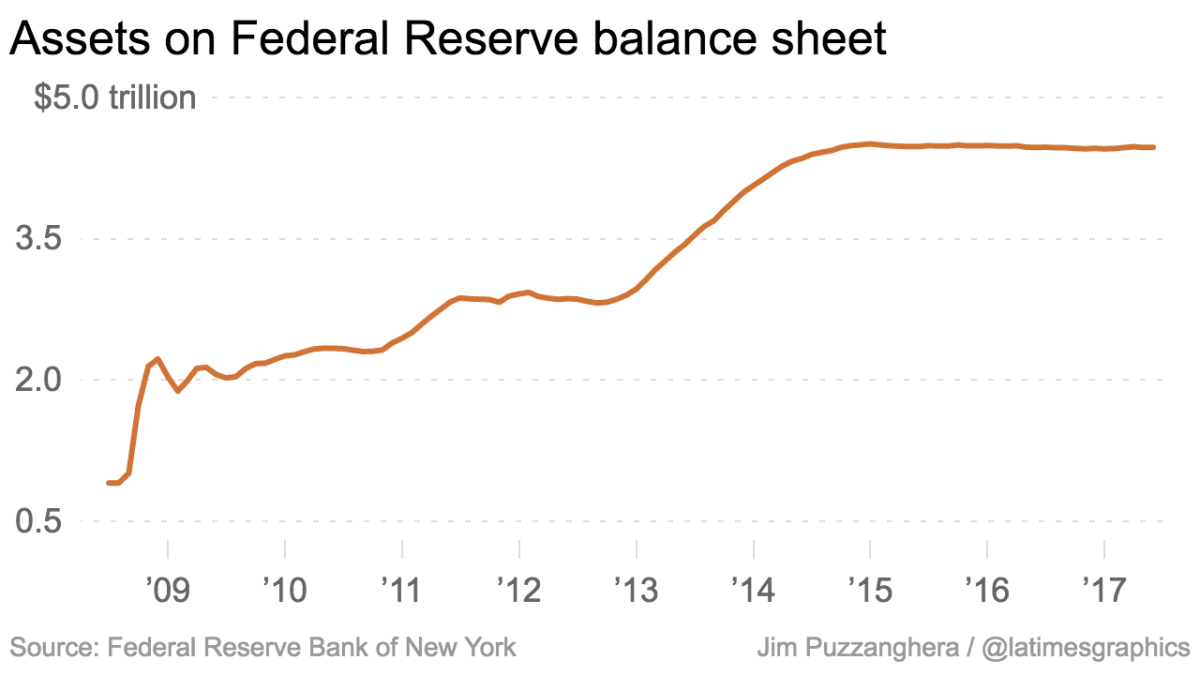

There’s one thing nobody disputes: The asset-purchases swelled the Fed’s balance sheet to unprecedented levels.

The Fed had about $900 billion in assets in late August 2008, just before the financial crisis hit. The total ballooned to about $4.5 trillion after the third round of quantitative easing.

It’s stayed at that high level since then because the Fed has reinvested the proceeds from maturing bonds into new ones instead of cashing them in. The Fed has done that to avoid the disruption of flooding the market with bonds, which would cause their prices to drop and push up long-term interest rates.

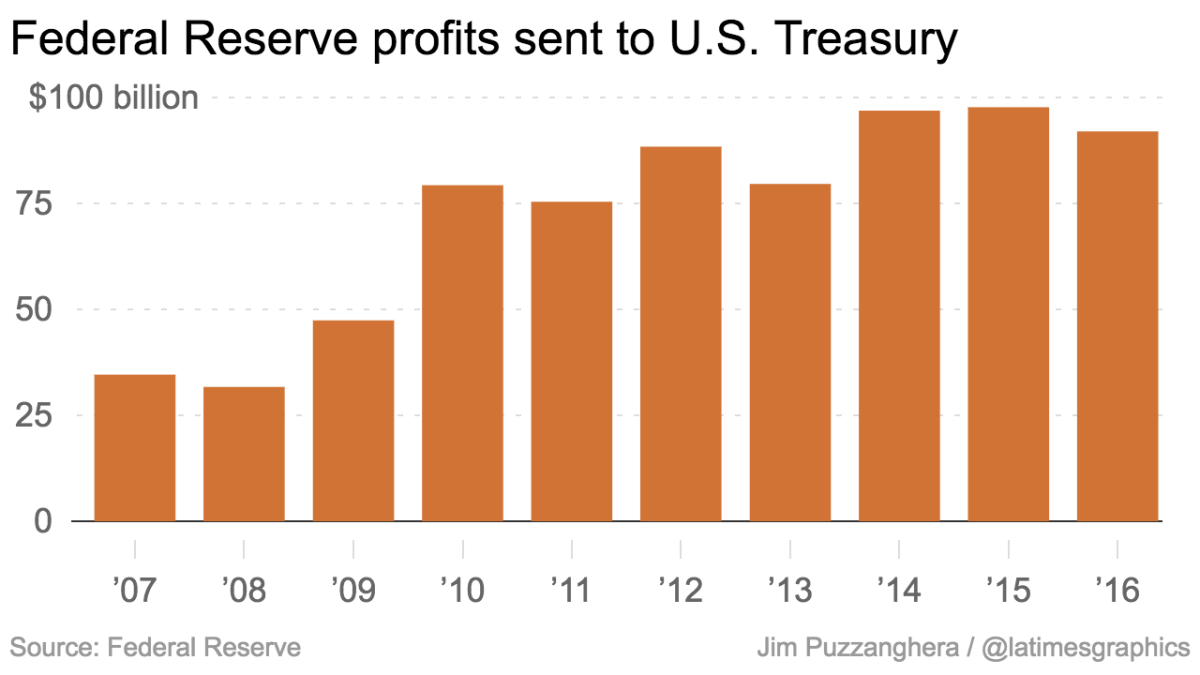

So far, the assets have been a boon to the federal government. They have kept long-term borrowing costs low, allowing the U.S. to cheaply finance its huge debt. And the Fed’s bond portfolio has produced a bumper crop of interest income for the central bank that has caused a jump in profit.

The Fed is self-funded and uses its income to pay for its operations, including issuing currency, and since 2010, funding the new

In 2008, the Fed sent $31.7 billion in profit. Since then, it has delivered a total of $657 billion.

But the bond purchases could have caused an opposite reaction. While the Fed’s purchases of mortgage-backed securities, in particular, helped a depressed housing market, the central bank could have been left with big losses had the value of these more-risky securities fallen.

On top of that, the Fed’s actions have been sharply criticized by conservatives, who argue that the central bank has no business inserting itself so heavily in the financial system, let alone supporting one industry — housing — over others.

“Is it the proper role of the Fed to decide whether the U.S. economy should be investing in mortgages, or it should be investing in solar cells, or investing in electric cars and stuff like that?” said John Cochrane, an economist and senior fellow at Stanford’s Hoover Institution.

Many Republican lawmakers would say no, and such arguments have fueled their efforts to rein in the Fed with further controls so that it sticks more strictly to its historical mission of controlling inflation. Yellen has fought such efforts as a threat to the Fed’s independence.

Critics also worry the Fed could start losing money on the assets as interest rates rise, which would reduce the value of the bonds on the central bank’s books.

Signs of that effect came last year after the Fed began inching up its benchmark short-term interest rate in late 2015. Fed profit hit a record $97.7 billion in 2015 but last year came in at $92 billion.

Fed officials have conceded that there could be a time when the central bank produces no income for a few years. But Yellen has said that should be more than offset by the profits the bond-buying has generated.

Tapering the Fed’s holdings without triggering a tantrum

After a small rate hike in March — the second in three months and the third since late 2015 — the Fed began hinting that the process of reducing its balance sheet could happen this year. The slow buildup was designed not to rattle investors.

The plan, described in minutes of the Fed’s May meeting, would involve allowing a small amount of the proceeds from maturing securities to be run off the balance sheet each month, with the amount increasing every three months.

In June, the Fed said the reductions in reinvestment would start at $10 billion a month and increase to $50 billion a month after 15 months. Fed policymakers said they would be prepared to stop the process if there was “a material deterioration in the economic outlook” that led to “a sizable reduction” in the short-term interest rate.

“The plan is one that is consciously intended to avoid creating market strains and to allow the market to adjust to a very gradual and predictable plan,” Yellen told reporters after the June meeting.

The Fed only plans to reduce the size of the balance sheet to about $4 trillion at the end of the 15-month period. Yellen said she and her colleagues anticipate reducing the amount of assets “to levels appreciably below those seen in recent years but larger than before the financial crisis.”

Experts anticipate that the Fed will stop its reduction when the balance sheet gets to about $3 trillion.

Such a slow and limited reduction in assets should be “imperceptible” to investors, Ablin said.

Still, he and others said there’s a risk that the move could lead to higher interest rates, perhaps with the housing market and home buyers facing the biggest hit.

“Home prices are moving far out of range of people’s ability to pay for it,” said Chris Rupkey, chief financial economist at Mitsubishi UFG Union Bank in New York, and that’s partly “because the Fed left borrowing costs too low for too long.”

Selgin sees another threat ahead: the possibility of deflation unless the Fed also reduces the interest it pays banks to hold their excess reserves.

The Fed began paying a small amount of interest on excess reserves during the 2008 financial crisis. The move gave the Fed more ability to manipulate its benchmark short-term interest rate.

That rate, the federal funds rate, is what banks charge to lend reserves to each other overnight to maintain their required daily reserve levels at the Fed. The interest rate on reserves above those levels helps put a floor on the federal funds rate because banks would not be willing to lend reserves for less than they could get by simply keeping them at the Fed.

Banks eagerly took advantage of the offer and total excess reserves — much of which were created by the Fed in their asset purchases — quickly skyrocketed from just a couple of billion dollars to about $2.7 trillion in 2014. The total has declined since then to about $2.1 trillion but still is exceptionally high.

In 2016, the Fed paid banks a total of $12 billion in interest for those reserves. The money helped the bottom lines of U.S. banks, which collectively earned a record $171 billion in profits in 2016, according to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.

Fed officials haven’t indicated if they will lower the interest paid on the reserves as the size of the balance sheet is reduced. By its nature, the reduction of Fed assets reduces the reserves created to pay for them. If the Fed keeps the interest rate on reserves steady, the combination would encourage banks to hold more reserves, pulling money out of the economy and leading to deflation, Selgin said.

Others are less concerned because of the slow and deliberate pace at which the Fed plans to reduce the size of the balance sheet.

“If they clearly articulate what they have in mind, everything is transparent and they’re very deliberate about it, for an economist, it will be more interesting than paint drying,” Zandi said. “But for the average person, it’s paint drying.”

Twitter: @JimPuzzanghera

ALSO

Treasury Secretary Mnuchin rejects speculation of tax hike on wealthier Americans

Strong June rebound signals job growth is solid again — but substantial raises remain elusive

Private-sector job growth slows to still-solid 158,000

UPDATES:

3:10 p.m.: An earlier version of this article said the Fed had about $900 million in assets in late August 2008, just before the financial crisis hit. The figure was $900 billion.

This article originally was published at 5 a.m.