The Silicon Valley entrepreneur moving black-hair products out of the ethnic aisle

This is probably the blackest this backstage room at the Dolby Theater is going to be for a while.

Granted, there are only two black people in the room — me and a 30-year-old guy named Tristan Walker — but considering that the Oscars will be held here in a week, that’s probably a safe assessment.

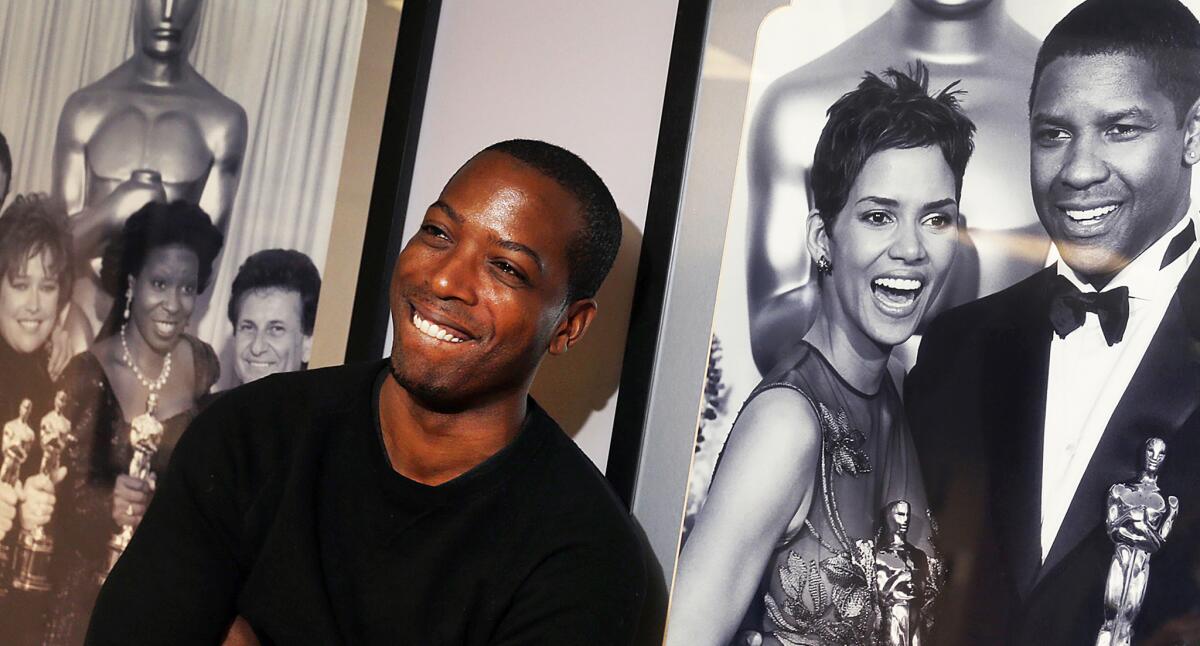

Walker is the founder and chief executive of Walker & Co. Brands, the company behind Bevel, a line of shaving products for men of color. I’m here to interview him, but he’s busy admiring a photo on the wall. The photo is of Halle Berry and Denzel Washington, proudly displaying their Oscars during that one historic moment in 2002 when two black people won the Best Actor and Actress awards.

Tristan Walker, founder and CEO of Walker & Company brands, photographed at the Dolby Theatre in Hollywood on Feb. 04, 2016.

Walker has flown down from Palo Alto, where he lives with his wife and son, to speak on a panel about diversity in tech start-ups along with Magic Johnson, who is also an investor in Bevel. In the two years and change since Bevel’s launch, the company has raised $33.3 million in funding, gotten nods from GQ, picked up a celebrity endorsement from Nas and this month went from an online-only product to a debut on Target’s shelves.

I’ve never so much as touched a Bevel razor, but I’m constantly hearing about it on Twitter, black fashion sites and on any one of several black podcasts. You may be wondering, like I was: Why is everyone so excited about a razor?

Walker tells me that Bevel started from a pair of frustrations. “A lot of global culture is led by American culture, which in turn is led by black culture,” he says. “And also Asian and Latino culture.” Too often, he says, those contributions go unrecognized.

The second frustration is the plight of what he calls the “ethnic aisle.” I’m already laughing when he says the words, because I know exactly what he’s talking about: the spot in every grocery store set aside for hair-care products for black and brown people.

“You gotta go back to aisle 15” — at this point, he’s laughing too — “but it’s not really an aisle, it’s just a shelf in the back, right? And you gotta reach down to the bottom of the shelf for some dusty package, and there’s a picture of a 65-year-old dude in a Jheri curl and a towel, and they’re assuming that I’m going to buy that product. It’s that whole second-class citizen experience.”

So for Walker, that feeling of being ignored by cosmetics companies was more than an annoyance — it was an opportunity.

Traditionally, we don’t think of grooming as being at the top of the list of conversation among men. But for a lot of black and brown men with coarse and curly hair, shaving is a daily ordeal, and a cheap multi-blade razor that works wonders on your white buddy’s face can turn your neck into something approximating Nestle Crunch.

This is how Walker says that his company differs from Venice-based Dollar Shave Club, another popular start-up. Dollar Shave Club offers razors starting at $1 (plus shipping) per month, and at $89.95 for a three-month supply of blades and shaving product.

Bevel can’t compete on price. But Walker is betting that customers will find that his single-blade razor, which he says is better for men that suffer from razor bumps, is worth the premium. The gamble seems to be paying off, because the company reports that 97% of customers renew their subscriptions.

“I get all these emails,” Walker says. “I just got one from a guy in the Army, saying something like ‘For as long as I can remember, razor bumps have been as much a part of my military career as my uniform.’” He counts black men in the military among his most enthusiastic supporters.

One engine of Bevel’s word-of-mouth success is sponsored podcasts. Black-run podcasts have a wide listenership, and it’s pretty common to hear the host of “The Black Guy Who Tips” or “The Combat Jack Show” go on an extended riff about the virtues of Bevel. Walker is enthusiastic about podcasters and rattles off a bunch of his favorites. “We sponsor a whole bunch of them,” Walker says.

These podcasts are popular in part because they reach a community that is often overlooked by other media. Because this is a community that is savvy about social media and vocal about what they like (and don’t like), when something comes along that speaks to them, they pay attention.

And sure enough, most of the online chatter about Bevel isn’t sponsored. It’s organic. DeRay Mckesson, a prominent activist who has recently announced his intention to run for mayor of Baltimore, recently tweeted that he had “only heard positive things” about Bevel.

“It was a pretty good point of validation for us, especially with all the really great work he’s doing,” Walker says. He admits that he gets excited whenever someone famous mentions Bevel online. “We send an email out to everyone, like, retweet! retweet!”

So much enthusiasm surrounds the company that there’s now a persistent rumor that Walker turned down a half-billion-dollar buyout offer from Gillette to keep his company black-owned.

“That’s not true,” Walker says. But he can understand why the rumor started.

“When my mother was growing up, she had SoftSheen Carson and ‘Soul Train.’ So I’m thinking about how can we build a company that this generation, and future generations, can be fundamentally proud to support? How much is that worth?”

It’s worth a lot, he says. People are proud of Bevel. “I think that’s why there’s this pent-up excitement,” which in turn fuels misquotes and rumors.

One of the masterminds behind the brand’s visibility is Cassidy Blackwell, who blogged about natural hair care for women for years before joining Bevel. She directs the content on bevelcode.com, a site staffed by Bevel employees. Most of the content would feel at home on a men’s fashion or hip-hop site: an interview with Nas about why he started wearing that “half-moon” part in his hair, photos of President Obama’s barber, recommendations for Valentine’s Day gifts and reviews of good barbershops in a handful of major cities. The site strengthens loyalty to the Bevel brand.

Bevel is a privately held company that doesn’t disclose its sales figure. But they seem confident about the future. Walker says they are getting ready to launch a line of products for women of color, and Bevel just announced two major accomplishments.

The first: After two years as an online-only subscription product, Bevel is now stocked on Target shelves because Walker struck up a relationship with a customer who left a glowing review from an @target.com email address.

“He turned out to be in charge of purchasing for personal care products,” Walker says. “Two months later we were in a meeting, a year later we were on Target shelves.”

Target seems pretty happy about the arrangement:

The second is the announcement of a new hand-held trimmer, accompanied by a celebrity endorsement of a rapper known for his intricate haircut: Nas. The endorsement was easy to get, Walker says, because Nas was the first investor in the company.

A pause. I stop Walker and ask him to clarify that he actually went and pitched Nas. Like, “I’m starting a shaving goods company, want to give us some money?” — just like that?

“Yeah.” Walker nods, as if asking a legendary rapper for cash to start up a shaving company is the most logical business decision in the world. “And the Queens connection helped too.”

So about a year into the business relationship, Walker asked Nas — who has invested in several tech start-ups — if he would be interested in helping the company market a new portable beard trimmer. He agreed immediately, and they produced a sleek ad for the device.

By creating a trimmer, Bevel is taking on decades of loyalty among professional barbers to time-tested brands such as Andis and Wahl.

But pre-orders are already rolling in, and thanks to relationships established via interviews at Bevel Code, celebrity barbers already talking the product up. One of the first in line: the personal barber for Barack Obama.

Walker’s drive for success isn’t surprising to his fans — yes, he has fans — who know at least a bit about his past. He was born in a rough neighborhood in Southside Jamaica Queens, N.Y., and after his father was killed when he was 4, he was raised by his mother. He went on to get an MBA at Stanford University, and was director of business development at Foursquare before landing at Andreessen Horowitz, the highest-profile and largest venture capital firm in Silicon Valley. Greg Bettinelli, a partner at Upfront Ventures, says that his company was interested in Walker even before he had an idea to pitch them. When he did, they wrote a check.

Walker & Co. (of which Bevel is a flagship brand) is located in Silicon Valley. It’s run largely by and for people of color, in a sea of companies that are overwhelmingly white, Asian and male.

Most of the company’s 22 employees are women and minorities, and it will probably continue to stay that way, Walker says. “We’re deliberate about that. I challenge anybody to say they have a more diverse team.”

Walker’s work doesn’t stop within his own company. He’s also the co-founder of an organization called Code 2040, which he launched with a classmate from his days at Stanford Business School. The name refers to an estimate of when people of color will make up the majority of the U.S. population.

The goal of Code 2040 is to create internship opportunities for black and Latino engineering students. More than 95% of the interns get full-time job offers from their companies.

“These are engineers who are really good,” Walker says. “So for a lot of these companies that say they can’t find [black and brown] engineers, they’re full of it. We’re proving that.”

The panel on tech diversity is about to start, and one of the organizers is waving to us to hurry up. Walker picks up his backpack and is about to walk out, but then he reaches into his pocket and pulls out his iPhone.

He wants a selfie next to that Halle and Denzel photo.

ALSO

There’s talk about bringing back the Black Oscars

‘The Day Beyoncé Turned Black’ is the best ‘SNL’ skit ever

The Oscars revolution has been messy, but diversity in storytelling deepens the art and enriches us